![]()

PART ONE

Arriving at Providence Canyon

IT TOOK SOME TIME to arrive at Providence Canyon. I do not mean that literally, as if describing one of my many visits to the park, though Providence Canyon is not easy to get to and will need locating before I move to the heart of the story. Rather, there was a significant lag of almost half a century between the initial development of the gullies that would come to compose Providence Canyon State Park and their discovery by outside observers intent on assigning them significance. Just as Providence Canyon is today a little-known local curiosity, so it was during its early history. Chapter 1 of this book provides a brief geographical and historical introduction to Providence Canyon, though I withhold important information about how these gullies developed for the end of the story. We do not want to arrive at Providence Canyon too quickly.

In the years just before World War I, two groups of scientific surveyors began showing modest interest in these spectacular gullies, making them known to broader constituencies. The first group to take in the visual spectacle was the Geological Survey of Georgia, practical scientists who were engaged in a revived effort to identify and map the state’s mineral resources. The second group to note the area’s broken territory was the National Cooperative Soil Survey, a joint federal-state effort to map the nation’s soil resources. Neither group paid more than glancing attention to Providence Canyon, at least initially, but the histories of each of these surveying efforts are critical to understanding the contest over Providence Canyon that developed in the 1930s. They help us make sense of why scientific attention arrived at the place at a particular moment in time, but they also speak to a shifting set of scientific and cultural understandings of geology, soils, and sublime scenery that soon made Providence Canyon a contested place. Chapter 2 examines the first part of that story: the history of geology and geological surveying in the nineteenth century and the rise of a geological aesthetic that would eventually contribute to Providence Canyon’s reputation as Georgia’s “Little Grand Canyon.” Since the study of soils was a subset of geology for much of this period, this chapter also contends with the early history of soil science and with the drifting apart of the two inquiries in the late nineteenth century. Chapter 3 focuses on the rise of the Soil Survey, the discovery by soil surveyors of the gullies of Stewart County, and the ways in which that discovery helped to set the stage for the emergence of soil conservation by the late 1920s.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Yawning, Abysmal Gullies

PROVIDENCE CANYON STATE PARK is located in Stewart County, Georgia, in the west-central part of the state, about forty miles south of the fall-line city of Columbus. Fort Benning, the home of the U.S. Army Infantry School, sits just to the north in Chattahoochee County, which separates rural Stewart County from metropolitan Muscogee County. Stewart County’s western boundary is the Chattahoochee River, much of it impounded in Lake Walter F. George, named to honor one of Georgia’s longtime U.S. senators. Alabama begins somewhere in the middle of the lake (Alabamans prefer to call it Lake Eufala), which is renowned for its bass, the game fish that has thrived in the novel ecological conditions of the South’s many dammed rivers. When the people of Georgia first elected Jimmy Carter as a state representative in a controversial 1962 election, Stewart County was in his newly drawn district, and by the time Providence Canyon became a state park in 1971, Carter had risen to the governorship.1 Indeed, the Carter family played an important role in Providence Canyon’s eventual preservation, and their involvement is one of its claims to fame. Today Stewart County is sparsely populated, with only about six thousand residents, and it is poor, with a quarter of the population living below the poverty line, almost double the national average. Stewart County is also heavily forested, with about 90 percent of the county land base now covered with trees, many of them plantation pine.2 But Stewart County was once one of the premier cotton-growing counties in Georgia, and in the entire South for that matter. The county’s massive gullies date from that former life.

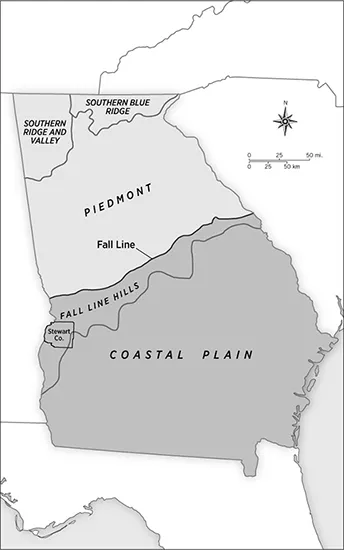

Stewart County sits on the cusp of several major southern physiographic regions and on the margins of what were once distinctive plantation areas. Physiographically, Stewart County is a part of the upper Coastal Plain. The county’s northern boundary is about twenty miles to the south of the Coastal Plain’s border with the Piedmont, the heart of the tobacco and cotton South in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the region better known for its long history of human-induced soil erosion. Stewart County is just to the south of the southwestern and last-settled portion of the Piedmont, and it lies squarely within the Fall Line Hills, a belt of rolling territory that extends south from the fall line and widens as it moves from northeast to southwest across the region. Geologically, the Fall Line Hills mark the meeting place between the sedimentary Coastal Plain and the much older hard-rock geology of the Piedmont. During periods of higher sea levels in the deep past, advancing and retreating shorelines shaped these hills.3 As a result, the county has unusual topographical relief for the Coastal Plain. From the Chattahoochee River, Stewart County rises through its hilly western portion to an upland plain almost seven hundred feet above sea level at its highest point. Just across the Chattahoochee from Stewart County lies the eastern edge of the Black Belt prairies, a crescent of lime-enriched and once-fertile soils that sweeps west and then north for several hundred miles through Alabama and into Mississippi. This is the physiographic Black Belt, not to be confused with the more expansive demographic Black Belt defined primarily by its plantation past and a large African American population. The Black Belt prairies, which were largely treeless in their precontact state, were rapidly settled and converted to cotton culture in the decades before the Civil War, an extension of the wave of settlement that spilled off the Piedmont and populated Stewart County. They contained some of the plantation South’s most productive soils, but this region, like the Piedmont, soon showed serious signs of wear and tear. Stewart County also sits on the northwestern edge of the southwest Georgia plantation region that was centered on Albany, Georgia. Again, beginning in the 1820s, cotton planters and their slaves arrived and converted the red lime soils of the Daugherty Plain along the Flint River into an outpost of the cotton kingdom. It was a place where, according to historian Susan O’Donovan, “slave society arrived fast, ferociously, and late.”4 By the eve of the Civil War, Southwest Georgia was one of the richest and most brutal regions of the cotton South. W. E. B. Du Bois later called it the “heart of the Black Belt,” a place where “the corner-stone of the Cotton Kingdom was laid.” By the time of the Civil War, Du Bois noted, many also called it the “Egypt of the Confederacy.”5 Stewart County’s simultaneous situation at the center of the historic “plantation crescent,” to use Charles Aiken’s useful descriptor, and its place on the margins of several key physiographic and cultural regions suggest some of the complexities involved in categorizing the place.6

Before Euro-American settlers and African American slaves began to arrive in the early nineteenth century, Stewart County had been a central place for southeastern Indian peoples for centuries, and its environment was shaped by their presence. Stewart County’s river frontage was the site of significant Mississippian settlements, and the county has two major mound systems along the Chattahoochee River to prove it.7 But those societies fell apart by the early seventeenth century as a result of Old World diseases and the political and social instability they wrought. In place of these Mississippian settlements there developed a series of “coalescent societies,” new polities such as the Creeks, who filled the vacuum left by the collapse of the older southeastern chiefdoms. New historical forces such as the deerskin and Indian slave trades reshaped their lives, pulling Indian peoples, often violently, into a world of market integration. By the eighteenth century, the Creek or Muscogee Confederacy dominated a large portion of what is today Georgia and Alabama, and the Lower Creeks made the Chattahoochee valley their home. What is now Stewart County was then at the southern end of the Lower Creek heartland.8

Figure 2. Physiographic regions of Georgia, adapted from Robert McVety’s master’s thesis. Note Stewart County’s location in the west-central part of the state, within the Fall Line Hills of the upper Coastal Plain.

Like the Mississippians before them, the Creeks were an agricultural people who concentrated their farming along the region’s active floodplains, taking advantage of fertile alluvial soils to grow corn, beans, and the other crops central to native agriculture in the region. The Creeks practiced shifting agriculture, clearing and utilizing sections of rich river-bottom land until its fertility began to wane and then abandoning those areas in favor of newly cleared bottomlands. The Creeks, in other words, were more than capable of diminishing the fertility of certain pieces of land over time. But several factors worked in the favor of agricultural longevity for the Creeks: they farmed alluvial soils that produced for long periods of time and were replenished periodically by sediment deposition; their intercropping of leguminous beans replenished soil nitrogen and controlled erosion; and while their numbers were substantial, their impacts were localized and easily repaired with time.9

Beyond these intensively managed riparian areas along the Chattahoochee and its tributaries, the Creeks had a lighter environmental impact. They hunted and gathered in the uplands, and they used fire to keep upland forests open and inviting to game. But their agriculture rarely made it to the hilly portions of Stewart County that saw the worst soil erosion in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. That may have been changing in the early nineteenth century, as their adoption of livestock and the cultivation of new crops such as cotton encouraged the Creeks to pull their settlements up the Chattahoochee’s tributaries. Creek agriculture was coming to look a lot like the agriculture of frontier whites, and vice versa, in the early nineteenth century, when frontier settlers first started moving into the region.10 But the early nineteenth-century conquest of these lands by white settlers and their governments thwarted Creek efforts at adaptation before they had made much of an imprint on the uplands. While Creek agriculture was sophisticated, dynamic, and syncretic, and while it reshaped portions of Stewart County’s landscape, the massive erosion that soon scarred Georgia’s western Fall Line Hills was a unique legacy of settler agriculture.

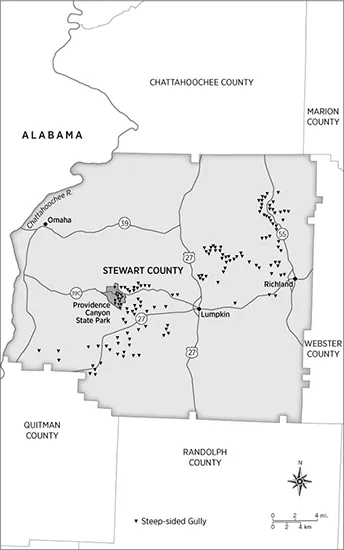

The network of canyons that makes up Providence Canyon State Park— the park actually contains sixteen steep-sided gullies—covers only eleven hundred acres, but large parts of Stewart County, and portions of several adjoining counties, are riddled with similar gullies.11 In the early twentieth century, soil surveyors estimated that forty thousand acres in the county, about 12 percent of its land base, were “rough, gullied lands.” In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Robert McVety, a graduate student in the Department of Geography at Florida State University, used satellite photos and the knowledge of longtime local residents to map as many of the steep-sided gullies in the county as he could find. When his work was done, he had found 159 substantial gullies (see figure 3), and he assumed that he missed a few because of the extensive revegetation that had occurred over the previous half-century, as agriculture retreated from the county.12

In search of some of these other gully specimens, I asked Bobby Williams, a long-time employee of the timber company MeadWestvaco and by several accounts the local resident with the keenest on-the-ground knowledge of the county, to give me a gully tour. He graciously obliged. I met Bobby one morning at the MeadWestvaco offices several miles north of Lumpkin, and he told me that he had half a dozen sites that he wanted to show me. In his enthusiasm, he ended up introducing me to many more. Within just a few hours of hitting the county’s network of unpaved secondary and timber company roads, we saw numerous prime specimens, a few of which rivaled Providence Canyon in scale and scenic qualities. Some were draped in kudzu and hard to make out, and one had been partially filled with trash before stricter sanitary landfill regulations came into effect several decades ago. But there are several enormous gullies still open to view if you know where to find them. Most of these other gullies remain little known, however. Only those that constitute Providence Canyon have become a state park and minor tourist destination. Discovering the others requires a sense of adventure, a good tour guide, and, in some cases, a machete.

The gullies of Stewart County began to form during the county’s early frontier settlement, some within a generation of the arrival of the first settlers, and they yawned ever wider as cotton took hold of the region. There is general consensus on that, although, as we will see, there are some intriguing theories about just how gully erosion began in the county. With Creek claims to the region extinguished by the Treaty of Indian Springs in 1825, the State of Georgia surveyed the land and then opened it to settlement in 1827 as part of the state’s fifth land lottery, though the first settlers had arrived a few years before that. The county, created from an adjoining one in 1830, was named for General Daniel Stewart, a native Georgian who served in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 but whose greater claim to posthumous fame would be his great-grandson Theodore Roosevelt. Conflict between settlers and Indians in the county persisted into the mid-1830s, and it peaked in 1836 when a group of several hundred Creeks burned the Roanoke settlement on the Chattahoochee River to the ground. Local residents called in the state militia to put down Creek raids, and fighting effectively ended with the Battle of Shepherd’s Plantation in June 1836. Settlement proceeded quickly thereafter.13 By 1840 there were 3,741 people in the county, all but one of whom was engaged in agriculture. Only five years later, there were 14,241 county residents, 5,744 of whom were slaves. By 1850 the slave numbers had jumped to 7,373 out of a total population of 16,027. The county’s population hovered around 15,000, about two and a half times its current level, for the rest of the century. As early as 1850, the county produced 7.6 million pounds of cotton, which made it one of the top three cotton-producing counties in the state.14

Figure 3. The gullies of Stewart County, Georgia. In a master’s thesis, Robert McVety located all of the steep-sided gullies that he could find in Stewart County. This map, adapted from McVety’s work, shows the extent of the county’s gullying. The cluster of gullies known as Providence Canyon is due west of Lumpkin.

Much of the early settlement of Stewart County fanned out along the fertile floodplain of the Chattahoochee River. Like the Creeks before them, early settlers and land speculators favored bottomlands as farming sites because of their accreted fertility, as long as they were not too swampy, malarious, or difficult to clear. Wealthy plantation owners—including, most prominently, General Robert Toombs, a Georgia senator who would briefly serve as the secretary of state for the Confederacy—soon controlled most of the county’s bottomlands. These lands were not only good for farming; they also placed planters just below the fall line and right along one of the most important transportation routes for marketing their crops.15

Following settlement patterns established on the Piedmont, planters and farmers shut out of the fertile but limited floodplain lands focused their energies on the adjoining and undulating section of the western part of the county, which was a mixed forest of oak, hickory, and shortleaf pine before agricultural clearance. Most settlers avoided the level lands in the eastern part of the county where longleaf pines dominated, following the general assumption of the era that pinelands were less fertile than those with hardwoods. This was not a bad assumption, as longleaf pines grow on acidic and well-drained lands that can be difficult to farm. There is also some evidence that the hilly sections of the county had an abundance of springs, which gave early settlers access to fresh water for themselves and whatever livestock they brought with them. Proximity to the river and the inexpensive transportation it provided was also im...