![]()

1

VALUING COMMUNITY

The Department of Neighborhoods' Origins

Local governments throughout the United States are facing a dual dilemma. Their resources are not keeping pace with increasingly complex social issues, especially when the federal and state governments are devolving more responsibilities than money to them. Voters are reluctant to approve additional resources because they feel a sense of alienation from their government at all levels.

The common response has been to “reinvent government” to be more like a business with a greater emphasis on efficiency and customer service. Although it is true that government needs to improve its business practices, there is a danger inherent in treating citizens as customers. To the extent that government treats citizens only as customers, citizens think of themselves only as taxpayers and feel that much more alienated from their government.

This deep sense of alienation is often misdiagnosed as apathy. Statistics showing that fewer and fewer people are voting and are joining community organizations have led some to the conclusion that increasing numbers of citizens no longer care about their community or their government. This analysis, I believe, blames the victim. Citizens don't vote because they have seen little evidence that their votes matter. The 2000 presidential election only confirmed what so many people already suspected: their votes didn't count. Likewise, people hesitate to join community organizations because they are tired of attending meetings that lead to nothing but more meetings. Whether they are participating in a planning workshop or a discussion of bylaws, too many people have a hard time seeing a positive relationship between their civic involvement and the quality of their lives.

I am convinced that people still yearn for a sense of community and want to contribute to the greater good. They also want a voice in their government. What they are looking for has less to do with reinventing government than it does with rediscovering democracy. True democracy requires deeper involvement than going to the voting booth once a year; people need to be engaged in their communities and with their government on an ongoing basis. People will commit to such involvement to the extent that they see results.

I say this with confidence because of the high level of citizen engagement I witnessed in Seattle between 1988 and 2002. Tens of thousands of people participated in implementing more than two thousand community self-help projects such as building new parks and playgrounds, renovating community facilities, recording oral histories, and creating public art. Thirty thousand people guided the development of thirty-seven neighborhood plans. Scores of new ethnic organizations and neighborhood-based residential, business, arts, history, and environmental organizations were established. Five thousand people a year were involved in cultivating plots at sixty-two community gardens that they built themselves. Organizations celebrated an annual Neighbor Appreciation Day, and individuals delivered eighteen thousand greeting cards to caring neighbors. Many people with developmental disabilities and other formerly marginalized citizens participated in community life for the first time. These are some of the many activities that accounted for survey results showing that 43 percent of Seattle's adults regularly volunteered their time for the community and 62 percent participated in at least one neighborhood or community organization.

Civic engagement created additional resources for the public good. P-Patch community garden volunteers generated ten tons of organic produce for food banks each year and maintained more than seventeen acres of public space. Community members invested more than $30 million worth of their own cash, materials, and labor in completing more than two thousand projects that they initiated. Likewise, broad-based ownership of the thirty-seven neighborhood plans led to voter approval of three ballot measures worth $470 million for library, community center, and park improvements recommended in the plans.

Perhaps more important than the financial and other material benefits of civic engagement are the social benefits of a stronger sense of community. No amount of public-safety spending can buy the kind of security that comes from neighbors watching out for one another. Similarly, neighbors supporting latchkey children or housebound seniors can provide a kind of personal care that social service agencies can't replicate.

There are other things that communities can do better than government can. Community members have local knowledge and can provide a local perspective. At the same time, they think more holistically than government departments that tend to specialize in specific functions.

The community is often more innovative than the city bureaucracy and can constitute a powerful force for change. When the City of Seattle planned to build incinerators to deal with its garbage problem, the community demanded a recycling program instead. When electricity rates escalated after the city bought into a nuclear power project, the community pushed for a model conservation program. It was the community that introduced the Seattle Police Department to community policing and insisted on its implementation.

Likewise, the community has power where city government does not. The city couldn't persuade the Seattle School District to host community school programs, but the community did. Government couldn't evict a pornographer from the sole theater in Seattle's Columbia City neighborhood, but the community did.

None of this is meant to suggest that there is no role for government. While the community provides a local perspective, government must look citywide to ensure that neighborhoods are connected and that each is treated equitably. Community innovation needs to be balanced by a certain amount of government standards and regulations. My point is simply that cities work best when local government and the community are working as partners.

True partnership requires government to move beyond promoting citizen participation to facilitating community empowerment. Citizen participation implies government involving citizens in its own priorities through its own processes (such as public hearings and task forces) and programs (such as block watch and adopt-a-street). Community empowerment, on the other hand, means giving citizens the tools and resources they need to address their own priorities through their own organizations.

In 1988, the City of Seattle had long been known, if seldom commended, for its emphasis on process. That year, the city made a sea change toward community empowerment with the creation of a four-person Office of Neighborhoods. The office quickly grew into a department that, by 2002, had nearly a hundred employees and a budget of $12 million a year. The Department of Neighborhoods differs from other city departments that are responsible for separate functions such as transportation, public safety, human services, or parks and recreation. Neighborhoods is the only department focused on the way citizens have organized themselves: by community. That unique focus enables the department to decentralize and coordinate city services, to cultivate a greater sense of community and nurture broad-based community organizations, and to work in partnership with these organizations to improve neighborhoods by building on each one's special character.

In subsequent chapters, I describe the department's programs to empower communities and recount stories that show some of the ways that citizens have used those programs to strengthen their organizations and neighborhoods. First, however, I want to describe how Seattle's elected officials came to create an Office of Neighborhoods and how I came to be its first director.

MY JOURNEY TO THE CITY OF SEATTLE

I arrived at my position with the City of Seattle via a rusty orange 1971 Volkswagen squareback. After graduating from college in the small town of Grinnell, Iowa, my wife, Sarah Driggs, and I looked at a map of the United States to help us decide where to make our first home. We were captivated by the concentration of blue and green in the northwest corner of the map and decided to move to Seattle. We bought the VW, loaded our few possessions into the back, and headed west. Having had little experience with a stick shift, we finally wrestled it into fourth gear and kept to the freeway as much as possible.

The map hadn't prepared us for the fact that Seattle is built on seven hills. We needed a home and found ourselves looking for an apartment on the steep slopes of Queen Anne and Capitol Hill. We needed money, and our job hunt took us through the heavy traffic of downtown, where we struggled to parallel park on equally steep slopes. Feeling hassled, lost, and anonymous in this city of half a million, we almost decided to keep moving to a smaller town.

Then we found an apartment in Wallingford, a neighborhood near the center of the city, just north of Lake Union. Our neighbors greeted us and made us feel at home. We soon became acquainted with the merchants in Wallingford's business district. We attended meetings of the Wallingford Community Council and discovered that we weren't so powerless after all. Wallingford, with a population of about six thousand, had a scale and feel not unlike Grinnell's.

It was in Wallingford that I discovered what it is that makes Seattle such a great place to live. Outsiders know Seattle for the Space Needle, Pike Place Market, and SAFECO Field; for Mount Rainier and Puget Sound; for Boeing, Microsoft, and REI; for the General Strike of 1919 and the anti-WTO demonstrations of 1999; for Jimi Hendrix and Kurt Cobain; for salmon and coffee; and for the incessant rain. But it's certainly not the rain that keeps most people in Seattle. I came to see that Seattle's greatest asset is the strong sense of community that comes from our vibrant neighborhoods. When you ask Seattleites where they live, they frequently answer with the name of their neighborhood: Alki, Ballard, Capitol Hill, Delridge, Eastlake, Fremont, Greenwood, Haller Lake, the International District, and so on.

Seattle has about a hundred neighborhoods. They are typically defined by the city's topography of hills, valleys, and bodies of water. Each neighborhood usually has a business district and a public elementary school. The average neighborhood—although there is really no such thing as an average neighborhood in Seattle—has about five thousand residents.

Virtually every neighborhood is represented by some form of a community council and often has a business association as well. These grassroots organizations, which advocate on issues, organize events, and sponsor projects, are independent of city government and independent of one another. The 1928 Handbook and Directory of the Federated Northeast Clubs of Seattle lists many of the same organizations that exist today.

When Sarah and I moved to Seattle in 1976, though, there were still some neighborhoods that lacked community councils. The neighborhoods with the greatest needs seemed to be the least organized to effect change. Given my long-standing interest in working for social justice and my newfound appreciation for community, I decided that my first job (aside from cleaning the Kingdome's restrooms on its opening day) would be as a community organizer.

I went to work for a Saul Alinsky–style organizing project started by two Jesuit priests in the low-income, racially diverse neighborhoods of Rainier Valley, Beacon Hill, and Georgetown. My fellow organizers and I canvassed door-to-door looking for potential issues and leaders that could serve as the basis for creating local neighborhood organizations.

Typically, I would introduce myself and ask if there were any problems in the neighborhood. All too often the response would be, “You can't fight city hall” or “Why, are you a lawyer?” In other words, politicians and lawyers were the only ones with power. We tried to give people a sense that they could create their own power by banding together around a common cause. It was a difficult job because people felt isolated and powerless.

One of our first organizing efforts was in the Empire-Kenyon Apartments. In our canvassing, we heard complaints about rent and utility rate increases, substandard housing conditions, rats, the lack of play equipment, and the need for a crosswalk signal on the adjacent street, a busy thoroughfare. The tenants felt so overwhelmed by all of these problems that it was difficult to bring them together around any one issue.

Then one day a child was killed while using the striped crosswalk on the busy street. We organized a community meeting and invited the Engineering Department. “What will it take before we can get a signal installed?” the chair demanded of the city representative. “Another death?” “No, two deaths” was the response. “We have standards.”

The community was so incensed that, the next day, people formed a steady stream of pedestrians, walking back and forth in the crosswalk, backing up traffic for blocks. The fliers they handed to the waiting motorists read: “Sorry for the inconvenience. We need a light to get traffic moving again.” The flier asked people to call the head of the Engineering Department—and gave his home phone number—to request a light. Shortly thereafter a traffic light was installed.

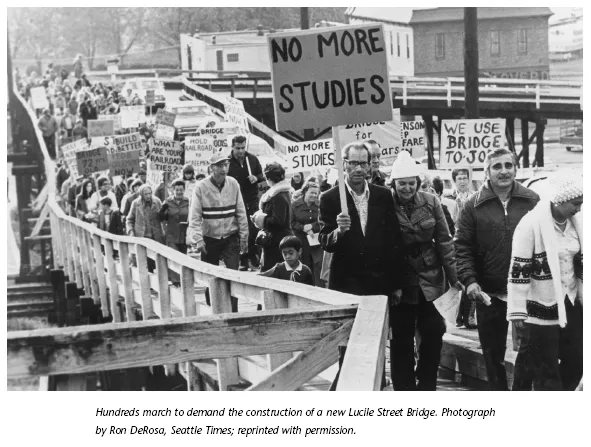

Similar tactics were employed in other neighborhoods. When Dunlap neighbors couldn't get the Building Department to inspect an illegal dump being created by a contractor, they removed a gigantic boulder from the accumulating pile and hauled it to city hall, where they dumped it in the director's office. When elderly and disabled tenants from Holly Park couldn't get Metro Transit to build a shelter at their bus stop, they invited newspaper and television reporters to come watch them build one for themselves. Angry tenants in the Gale Place Apartments converged on and surrounded the waterfront home of a slum landlord, some arriving by bus and the rest by boat. Six hundred neighbors and union members marched across the rickety South Lucile Street Bridge to a meeting with elected officials, where they demanded that the failing structure be replaced. A Seattle School Board meeting was interrupted by Chinese American students from Cleveland High School performing what they feared would be their last lion dance, because students of color were being bused to other schools. When the mayor, under pressure from the federal department of Housing and Urban Development, backed down on a campaign commitment, a community delegation released a chicken in his office.

Although these and other actions were successful in effecting change, the victories were not the ultimate goal. The goal was to use the victories to build ongoing neighborhood groups so that the power that had been developed through each issue campaign could be sustained and applied to other issues. Once several neighborhood groups had been established, we brought them together with local churches to form the South End Seattle Community Organization. SESCO grew to include twenty-six member groups over the six years that I worked for it as an organizer and director. As many as eight hundred people attended annual conventions at which the members elected officers and voted on community-wide issues that they wanted to work on together. Among those projects was a fight against garbage incinerators, which led to a citywide recycling program, opposition to the overconcentration of low-income housing, which resulted in a scattered-site housing program, and a local ratepayers' revolt by SESCO's Light Brigade, which quickly grew into a successful statewide campaign against nuclear power.

My experience with SESCO taught me three valuable lessons about organizing that have guided my work ever since. The first is to start where people are. Most important, this means organizing people around what interests them rather than around what you think they should be interested in. It also means respecting people's culture and communicating in their language, utilizing existing networks instead of trying to create your own, and meeting with people where they are accustomed to gathering.

The second lesson is to organize people around issues that are immediate, concrete, and achievable. It's difficult to bring together community people to do long-range planning, to address a vague problem like “public safety,” or to take on a huge issue like nuclear disarmament, but it is relatively easy to bring together people for a specific, achievable task to address an immediate issue, for instance, to plan a course of action to remove violent video games from a local arcade following a neighborhood shooting. Once people have a sense of power because they have succeeded with small issues, they are readier to tackle issues that are larger and take longer.

The third lesson is one that my mentor, Tom Gaudette, drilled into me: “Organizers organize organizations.” The organizer's role is to build an organization, not to be the leader in winning an issue. Issues are one tool that the organizer can use to develop leadership and help build the organization so that it is broad based and self-sufficient. The best organizers don't foster dependency; they work their way out of their jobs.

I took these lessons with me to Group Health Cooperative in 1982. Group Health had been founded in 1947 by members who mortgaged their homes and by physicians who were ostracized by the medical establishment because they wanted to create a cooperative to make health care affordable to the working class. By 1982 Group Health had grown to become the nation's largest health care cooperative, with more than 300,000 consumers, and had begun to lose sight of the very thing that set it apart: membership ownership and participation. To try to reengage members in the governance of their organization, the cooperative's board of trustees created a Cooperative Affairs Department. As an employee of Cooperative Affairs, I worked to build membership-based groups: medical center councils that reviewed clinic budgets and quality of care, special interest groups for seniors and antinuclear activists, and Partners for Health, a group supporting a sister clinic in Managua, Nicaragua. I also staffed the annual membership meetings, which attracted as many as 2,500 people. I was intent on making the cooperative more responsive to its members, becoming a model for the nationalized health care I hoped was on the horizon.

Our department was able to do this work as part of management, because we took extreme care not to cross the line between organizer and leader. We never advocated the positions of management or of the membership. Instead, we made it possible for managers, medical providers, and members to work together.

In 1988, I got the opportunity to develop a similar model for the City of Seattle. Mayor Charles Royer appointed me the first director of the new Office of Neighborhoods. This was the same mayor whose house I had picketed and whose office we had be-fowled during my time at SESCO. I never did figure out why he hired me, but clearly, he was no chicken after all.

My first days on the job rid me of a couple of other misconceptions. I quickly learned that my stereotype of bureaucrats as uncaring and lazy was largely untrue. People tend to work for city government because they want to be of service to the community, and the bureaucrats I met worked very hard. I did see that many good public servants are trapped in bad systems, and saw too that they are as...