![]()

CHAPTER 1

MEASURE FOR MEASURE

You can't manage what you don't measure.

—PETER DRUCKER

Measurement systems are symbolic representations of the real world. Effective measurement systems are standardized, verifiable, and widely adopted. This last qualifier is important: The value of a measurement system (or symbolic representation) as a communication tool increases as more people use it because the number of possible interactions that can leverage the measurement system goes up exponentially. If two people agree on a measurement based on the length of a maple leaf, it's not very useful to anyone who doesn't know the size of that leaf. But across the world, the length of a meter is a consistent measure that enables communication about length and distances among cultures and between people who have never met.

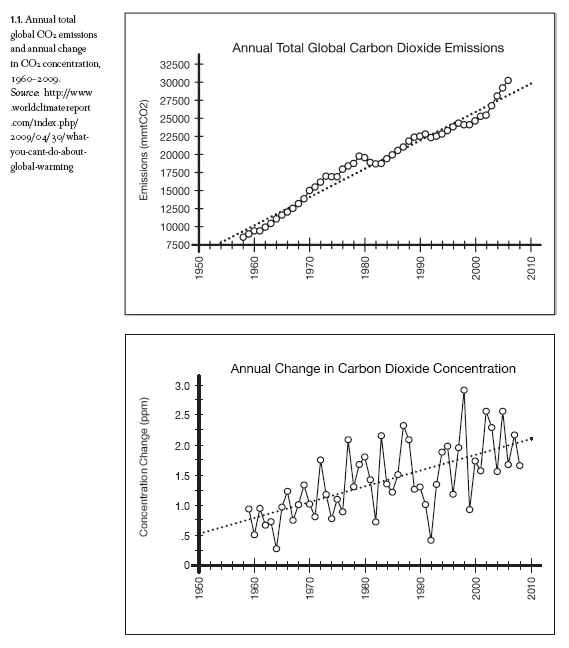

Atmospheric CO2 gas, expressed in parts per million, is the widespread measure of the level of carbon in the earth's atmosphere. To reduce our carbon emissions, we also need to be able to measure our output at an emitter level. In recent years we have measured CO2 output from processes in terms of pounds or tons of CO2 per year. Figure 1.1 shows how global CO2 production has increased since 1960 and the resultant change in CO2 concentration in the atmosphere over the same period.

So far this is fairly simple, but it gets more complicated. Monitoring the amount of gas emitted by every activity from breathing to lighting a campfire is not feasible; we can't install a meter on everything in the world. The more practical solution is to monitor some fundamental processes in a controlled environment—for example, the burning of a liter of oil—and then create models to reflect the CO2 emissions of real-life activities. What is most important is that everyone uses the same measurement system, the same process boundaries, and the same models so that we can communicate clearly and efficiently about carbon outputs. In reality, models aren't perfect. Near-perfect models—ones that reflect all of the variability and nuance of the real world—are too big and complex to be computationally tractable and too large to be easily verifiable by observation. More important than the need for perfection is the need for a model that is basically correct, that measures what we really want to change, and that is widely adopted.

If a model is widely used, communication happens easily and quickly. Putting this into economic terms, a standardized CO2 measurement system will lower transactional costs between people using the model, because they can quickly come to a common understanding. Furthermore, if everyone adopts a standard measurement system or model, it can be refined over time as more and more people become conversant in the science and technology surrounding carbon emissions. If everyone is focused on refining one model for measuring CO2, efforts will be directed in a cumulative and efficient way into improving that standard.

RECOGNIZING EFFECTIVE MEASUREMENT

A simple example of a standard that improves transactional and communication efficiency is the metric system. Across most parts of the world standard metric units are incorporated into other systems and models. This has simplified communication about these systems and models around the globe because virtually all countries use the same metric system as their standard. By contrast, for many Americans operating in the international arena, the United States's failure to adopt the metric system provides a daily object lesson in the inefficiencies of operating with a unique system that other players do not employ.

Of course, the metric system is a fundamental unit of measurement, so it doesn't have some of the modeling issues that other more complex systems of representation face. The challenge in modeling a highly variable situation with a simple system can be seen in a look at commodities trading. If we tried to use a model that accounted for the vagaries of each pig or each pound of coffee or each pound of frozen orange juice, there would be too much information about each unit to make trading efficient. Commodities markets work because the units they use are standardized. Investors trade frozen pork bellies, the commodity measure used for commercial supplies of bacon and other pork products, in contracts representing exactly forty thousand pounds of twelve- to eighteen-pound frozen bellies.1 Enterprises that subsequently take physical delivery of the pork have an agreed system for making minor price adjustments that correspond to the specific characteristics of the physical items they receive. The market functions efficiently because everyone dealing in pork futures trades in it. While some pig farmers would undoubtedly argue that the uniform metric fails to capture the unique and valuable characteristics of the pigs they raise, the standard is indispensible because it provides a common ground in a way that multiple markets for different types and sizes of pigs could never achieve.

It is always tempting, in light of the imperfections of almost any standardized system, for organizations to decide that they need to come up with a version more tailored to their particular situation. Generally, however, the benefits of having a slightly more “perfect” model do not outweigh the advantages of the common standard in its communicative efficiency and its ability to continuously improve over time. For example, in 2007, King County in Washington determined that its State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) process needed to include a system for evaluating projects in the built environment according to their greenhouse gas emissions. This was a move in response to political targets set at the state level for curbing emissions. The county spent several months engaging stakeholders from industry and government in developing a measurement and goal system for embodied, operational- and transportation-related emissions from the built environment. Throughout the process the stakeholders struggled with balancing their model's accuracy with its complexity. There was also significant concern about the additional reporting burden the new county model would impose on the private sector, as well as the additional administrative and review burdens that the county would impose on itself.

In the end King County wound up providing an alternate review and reporting path whereby if a project met the existing Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold standards, it was deemed energy-efficient (and carbon-efficient) enough to be meeting the state's targets. Stakeholders became comfortable with using the LEED Gold standard when they reviewed performance data on past projects and concluded that LEED Gold buildings did in fact perform at energy efficiencies that met the county and state targets. Despite the challenging targets set by LEED Gold, developers were relieved to avoid one more layer of reporting costs, and the attendant lag time while the county reviewed the data. A corollary benefit is that LEED undergoes continuous improvement with the help of many more resources than the county could ever marshal over time. As a result, the LEED standard has the potential to evolve and remain up to date in a way that the county's reporting mechanisms could never hope to achieve.

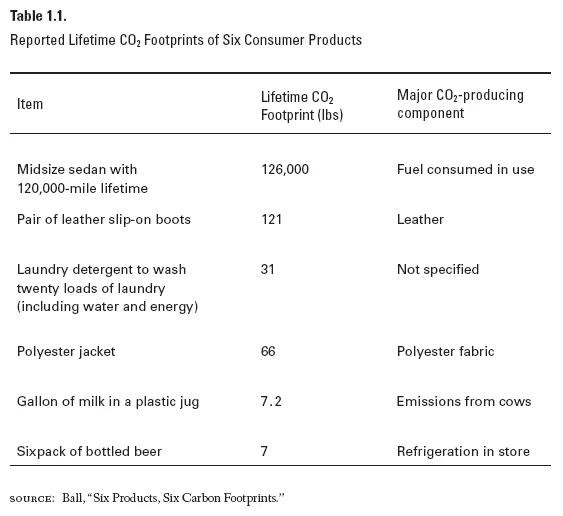

On the flip side, the absence of a clear, shared standard is not merely inefficient; it can actually lead to flawed comparisons and false conclusions. An article that first appeared in the Wall Street Journal in 2008 provides a classic illustration of the current lack of standards for quantifying carbon emissions.2 Reporter Jeffrey Ball undertook a review of six consumer products to understand their true life-cycle carbon impact. He came up with the results summarized in table 1.1.

Life-cycle analyses vary in what they measure, but they generally include all the carbon impacts associated with production, transportation, operation, and disposal of a product. What is most important when comparing life-cycle impacts is to use a consistent modeling methodology; otherwise, the comparison from one product to another is meaningless. In his introduction Ball noted that “different companies are counting their products' carbon footprints differently, making it difficult for shoppers to compare goods.”3 Ball attempted to normalize the results, but he found the different standards that had been applied made it all but impossible. In some cases disposal was considered, in others not. In the case of milk, the CO2 generated in producing the feed consumed by the cows was not counted. It's easy to see how such an article, intended to make consumers more educated and aware, succeeds mainly in showcasing the complexity of the problem, because there is no standard for how we measure or model life-cycle emissions from consumer products.

HOW WE CAN IMPROVE MEASUREMENT

STRATEGY #1: Adopt a national standardized model and accounting practices for measuring greenhouse gas emissions as a necessary building block for managing a carbon-efficient economy. Support evolution of national standards and align them with emerging international standards.

Federal Government

Adopt the leading system in the market—even if it's not perfect—in developing policy, incentives, or regulation.

Given that the value of a measurement system is derived largely from the network of the effect of being shared among many users, it makes sense that there is a role for the federal government to play; many other important shared standards from generally accepted accounting practices (GAAP) to nutritional labeling of foods operate at a national scale and benefit from a national platform. The federal government is also the connection point to international goals and initiatives. When a federal government is a signatory to a treaty that sets goals for greenhouse gas emissions, there is an implied measurement system that the signatories can use to account for and demonstrate their success. The federal government is the natural body to translate international goals to meaningful national and regional targets.

Thus far, international emissions targets have tended to be relative, as in “by 2050, emissions will be reduced to 80 percent of 1990 levels.” This sort of relative target has the benefit of being easy to scale. If we want the world's emissions to be reduced to 80 percent of 1990 levels, we can also hold each country or region to that standard. The problem with this type of scaling, however, is that population and economic activity in different countries and regions are changing, with some experiencing more rapid growth than others. Converting the target to a per capita number might be possible, but if we want to be able to really manipulate data effectively and correct for a variety of variables, we need information about absolute emissions.

At a macro-level, carbon markets in Europe have adopted standard assumptions about the emissions related to different activities and energy transformation processes. At a micro-level, the science around modeling the energy use and emissions from buildings is growing more detailed and more standardized every day. Federal governments need to work together globally and quickly to converge on these standard measurement systems as they emerge and use them to translate international goals into national, regional, and local goals. As the federal government creates incentives or regulation to reduce emissions, the ability of the economy to assimilate and respond to this change will be substantially affected by how quickly and consistently it is able to apply measurement tools that link the micro and macro analysis together. Even if a measurement system emerges that is not perfect, it is likely more effective to engage in supporting and influencing it rather than to create an alternate system with all of the attendant “translation” costs.

Establish clear national goals for carbon emissions and subgoals for smaller time intervals and regions.

Another way in which the federal government can play an important role in encouraging standardized measurement is to articulate a breakdown of large-scale targets into smaller geographic regions and time increments. To this point, most of the regional target-setting within the United States has been done from the bottom up, either by states and multistate alliances such as the Western Climate Initiative or by municipalities, often through vehicles like the Conference of Mayors. These grassroots efforts are important, but the federal government has the ability to generalize these goals across the whole country—avoiding first-mover disadvantages to regions that choose to act.

Equally important, they can create a framework that aggregates the contributions of different regions and improves understanding of how the country as a whole is meeting broader global targets. In the business environment the mnemonic PDCA (plan, do, check, act) is frequently used to describe the standard and goal-setting process.4 The actions required of the federal government in support of standard measurement systems, broad goal setting, and subgoal articulation is depicted in table 1.2.

Table 1.2.

Steps Required to Establish a National Standard Greenhouse Gas Measurement System

| PLAN | Adopt and support the standard measurement system. Set national and regional targets in absolute terms and with time horizons. |

| DO | Implement appropriate legislation and policy to send signals to the market about the application of the standards. |

| CHECK | Track progress on targets; evaluate how evolving measurement tools are impacting adequacy of goals and progress. |

| ACT | Tweak policy levers to clarify market signals. |

State and Local Governments

Adopt national standards so that companies can innovate and reap the benefit at a national scale.

State and local governments also need to adopt the common standard. They are in a unique position to provide feedback about where the measurement standard is failing in practice. Without doubt, refining the measurement system will take time, and initially there will be gaps between the model and the reality that can skew incentives if appropriate adjustments are not made.

Provide feedback to the federal level.

State and local governments also need to provide feedback about what regional subgoals are most appropriate. Even with a system of measurement that has the clarity of absolute numbers, there will be (and needs to be) intense debate about what other economic and social goals are to be balanced with emissions targets. This discussion is rife with potential for clashes among local interests—state governments will play a crucial role in deciding how these issues get arbitrated.

Environmental Nonprofits and Private Sector Companies

Generate standards, adopt leading standards, and monitor their integrity.

Nonprofits and businesses, not government, are in the best position to develop a measurement system. Many important measurement systems have come out of the nonprofit research community and the private sector, where actors are driven by the need to pursue a goal in the most efficient way possible and to convey an idea quickly and simply to clients or the public. It is difficult to overstate the enormity of the contribution made by the nonprofit International Organization for Standardization through its 18,500 international ISO standards covering everything from agriculture to information technology.5 The U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) has developed the LEED certification standard mentioned earlier, which is now a leading indicator of sustainable buildings, campuses, and neighborhoods. In both cases the rating systems have been successful for a few different reasons:

» They have built strong brand recognition, so that people who want to use the information don't have to replicate the analysis, but rather can trust the result.

» They have been refined over time in response to changes in the practices of the analyzed entities (companies and buildings).

» They are seen as an independent, and therefore trustwo...