![]()

1

THE WETLAND ARCHIPELAGO

THE WORD “FLYWAY” conjures up visions of an aerial highway that birds follow up and down the continent, taking rest stops along the way. But the word is misleading. There is no interstate in the sky for the birds to follow. Ornithologists realize that beneath the simplicity of the flyway concept lays a very complicated network of crisscrossing migration paths. Despite these limitations, wildlife managers still use flyways as a management tool. In the words of one nature writer, the Pacific Flyway is a “way of thinking about ducks.”1 Although biologists now have more sophisticated understandings of bird migration than they did when the concept was developed in the 1930s, it does capture one basic fact of North American bird migration: along the Pacific coast, waterfowl migrate between the ocean and the flanks of the main mountain ranges. Birds can and do cross these mountains while migrating, but many species of waterfowl follow the general north-south trending ranges.2

Except for the northern part of the continent, where wetlands were extensive and plentiful, most of the area encompassed by the Pacific Flyway was useless to waterfowl even before people began draining wetlands on a large scale in the late nineteenth century. Ducks, geese, and swans need wetlands to survive, and the degree of their dependence varies by species. Most waterfowl nest on or near wetlands. Although birds migrate across vast distances, their journeys bring them to environments similar to ones they left. A goose would breed in a wetland in Alaska, stop to feed in a wetland in British Columbia or Oregon, and spend the winter in a wetland in California.3

Until the nineteenth century, people did not radically alter or drain wetlands along the Pacific Flyway on a large scale. This does not mean that they were pristine sites free from human use. The enormous productivity of wetland environments made them attractive to Native peoples from Alaska to Mexico. Although they had a significant impact on wildlife numbers using these wetlands, their technologies limited their ability to alter the hydrology of western marshes and estuaries. Native peoples neither diverted major rivers nor filled wetlands. Until the nineteenth century, the distribution of wetlands, and their formation or disappearance, was largely the product of natural forces.4

Yet the fact that humans had only minimal impact on the hydrology of western wetlands does not mean that these wetlands were timeless. Change defines the natural history of these places. Focusing on the wetlands just prior to their destruction in the nineteenth century can create a misleading impression of their characteristics. Wetlands were dynamic environments before people began to drain, dike, and fill them, and the degree of dynamism differed from area to area. This dynamism operated over short courses of a few years and over longer periods of centuries and millennia. During the Pleistocene, for example, ice covered most of the current breeding range of migratory waterfowl. Waterfowl were therefore geographically limited to regions south of the ice sheets that covered most of present-day Canada and Alaska. As the ice sheets retreated between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago, many areas were opened to colonization by plant species and, eventually, by migratory birds. Waterfowl migration is partially an adaptation to this change.5

By migrating, waterfowl and other birds were able to take advantage of the seasonal abundance of resources available in the Arctic and subarctic during the summer, and then retreat to lower latitudes before the onset of winter. But long migratory journeys exposed them to dangers en route, as well as to the possibility that drought would dry up wetlands in either the wintering or breeding range. For many species of birds, migration was necessary and unavoidable, but it exacted a cost. The cost became all too apparent to conservationists hoping to save migratory waterfowl as western marshes and estuaries were lost to agricultural and urban development.6

THE PACIFIC FLYWAY WATERSCAPE

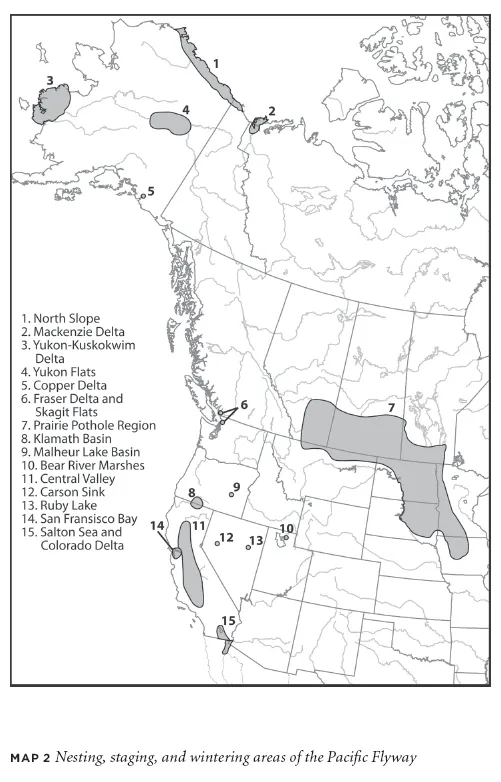

Pacific Flyway birds annually migrated to wetlands separated by thousands of miles. Prior to the nineteenth century, wetlands were more common in the northern reaches of the flyway than in the southern portion, where aridity and topography restricted their development. Although wetlands and lakes were abundant in the Arctic and subarctic, they were not all equally useful for waterfowl. River deltas supported the highest numbers of waterfowl. During their annual migrations, birds migrated from these northern wetlands to marshes and estuaries in the western United States and Mexico. Their journeys took them from Arctic deltas to wetlands in some of the driest deserts in North America.

The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta on the west coast of Alaska formed the largest and most important wetland complex in this northern region. Between the lower stretches of these major rivers, a tapestry of bogs and marshes formed that covered over 26,000 square miles. During the summer breeding season in peak years, over 750,000 ducks and 500,000 geese could be found within this delta. All the cackling Canada geese found in North America nested in the delta, and most of the white-fronted geese that traveled along the Pacific Flyway bred there, too. For snow geese migrating from their breeding ground on Wrangel Island in Siberia, the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta was an important stopover on their journey to California's Central Valley. The upper regions of the Yukon River (known as the Yukon Flats) were also critical habitat for waterfowl. Over 40,000 ponds and lakes flanked the river. Together, these wetlands provided nesting habitat for a significant portion of Pacific Flyway waterfowl.7

The drainage basins of other major rivers also provided habitat for ducks, geese, and swans. The Mackenzie River was the most important in northern Canada. Waterfowl researchers in the 1960s compared the Mackenzie River system to a giant staircase stretching from the Arctic into more southerly parts of Canada. Inland deltas were found along each step or landing along the Mackenzie River and its major tributaries. Toward the headwaters of this system, the Peace and Athabasca rivers formed a delta on the southeast shore of Lake Athabasca. The remnants of meander channels from both rivers created an ideal habitat for waterfowl. Ducks and geese fed on marsh plants like sago pondweed and alkali bulrushes that grew in abundance. The most serious threat to birds using the area was not drought, but flooding, which could wipe out waterfowl nests. This could have severe consequences if a flood occurred in the peak nesting season (June and July). The population of waterfowl using the delta during the summer could range from 84,000 to 250,000 birds. Other rivers in this system also formed deltas when they entered large lakes. The Slave River, for instance, formed a delta when it reached Great Slave Lake, which served as an aquatic nursery for waterfowl. The largest delta formed where the Mackenzie River emptied into the Beaufort Sea.8

Widespread though they were, the wetlands and river deltas of the north were not nearly as productive per acre as wetlands farther south, particularly on the Canadian and American prairies. Wetlands were common in the northern boreal forests, but the soils were poor and supported fewer of the marsh plants ducks and geese needed. Since drought occurred less often in the north than it did on the prairies, the northern wetlands were nonetheless more dependable from year to year. The sheer size of the northern wetland area also meant that it could support large waterfowl populations. Also, the dispersal of waterfowl over the vast territory meant that poor conditions in one part of the region would not have devastating consequences to waterfowl in other parts. Even more importantly, the northern region served as a place to which ducks and geese could retreat when droughts dried up wetlands on the prairies. Therefore, in addition to being an important breeding area for waterfowl every year, northern wetlands and deltas functioned as a safety valve for birds along the flyway. Ducks and geese could depend on the relatively pristine and drought-free areas in the north when conditions deteriorated on the prairies. As we shall see, the situation was considerably different in the wintering range.9

These northern areas were an opportunity and a problem. Although Alaska and northern Canada made up one of the largest wetland complexes in the world, waterfowl could only use them during the warmer months each year. Once winter arrived, waterfowl needed to migrate to areas where food was plentiful and open water was available for feeding and resting. Waterfowl migrated to the northern reaches annually, but they had to retreat quickly at the end of summer. Without dependable, high-quality wintering habitat, these northern areas were useless to waterfowl.

None of the wetlands in northern Canada or Alaska could compare to the incredible productivity of the Prairie Pothole area, a region of thousands of small ponds and marshes straddling the Canada-U.S. border. Although the area only contained a tenth of the duck-breeding area in North America, the Prairie Potholes supported between 50 and 80 percent of the continent's breeding ducks during the summer. Since most of these ducks migrated along other flyways, the region contributed fewer ducks and geese to the Pacific Flyway than the northern regions. If the Pacific Flyway were a river, the waterfowl from the Prairie Pothole would be tributary to the main stem of birds coming from Alaska and northwestern Canada.

The reason for this area's productivity lay in the extensiveness and types of wetlands found there. The region is dotted with small ponds and marshes (most only a few acres in size) that formed at the end of the Pleistocene when the Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated, leaving blocks of ice in what is now southern Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. These “potholes,” known as kettles, later became ponds and marshes. In some places the density of potholes reached almost 40 per square kilometer. The exact number of potholes that existed prior to agricultural settlement of the Prairies is difficult to estimate because they were so numerous; some studies suggest that over ten million existed in Canada and one million in the United States.10

Changes in precipitation in the region from year to year made the potholes dynamic environments. In the fall, most potholes were dry or contained very little water. During the spring, they refilled with melting snow or rainwater, which evaporated over the course of the spring and summer. By late summer or early fall, many potholes would be dry once again. The way waterfowl used these freshwater marshes differed by species, but the diversity of pothole types and the length of time they contained water was part of what made them so attractive to these types of birds. Mallard and pintail ducks used a number of different types of potholes throughout the breeding and wintering season. Seasonal potholes often had plentiful insects in the late spring, which was when ducks had higher protein needs for breeding. At other times, ducks sought out potholes with dense vegetation to shelter their young. Over the course of the breeding season, ducks used between seven and twenty-two different potholes. Although each pothole was important, the assemblage of wetlands is what made this area so vital for waterfowl.11

Waterfowl could not rely on the availability of pothole wetlands every breeding season. During drought years, potholes often failed to fill with water or the water evaporated early in the season. Without pothole wetlands, waterfowl were forced to fly elsewhere to find breeding habitat. This usually meant flying farther north to wetlands in the boreal region or river deltas. Although wetlands in northern areas were less prone to drought, they were not as productive as prairie wetlands. Even with these “back-up” northern wetlands, drought years led to sharp declines in waterfowl populations. Yet this dynamism was partly responsible for the productivity of prairie wetlands: the repeated drying and flooding of potholes allowed emergent marsh vegetation to flourish.12

Prairie Pothole wetlands were extremely vital for North American waterfowl as a whole. Yet they contributed fewer birds to the Pacific Flyway than they did to the continent's other principal migration routes. The pothole region was the primary breeding ground for the ducks that migrated along the Central and Mississippi flyways. There were exceptions to this general trend. For instance, most northern pintails and mallards found along the Pacific Flyway bred in the Prairie Potholes and wintered in the Central Valley of California. The relatively small contribution of Prairie Pothole birds to the Pacific Flyway had a number of implications. It meant that the draining and filling of Prairie Potholes in the twentieth century would have less impact on Pacific Flyway waterfowl populations than on the waterfowl of other flyways; most of the wetlands in the breeding range of migratory waterfowl along this flyway were not seriously affected. Even in the late twentieth century, northern wetlands in Alaska and Canada remained little altered by humans. Also, drought cycles, which periodically dried pothole marshes, were common in the Prairie Pothole region, but occurred less frequently in the breeding range of most Pacific Flyway waterfowl.13

Unlike the primary breeding areas for Pacific Flyway waterfowl, which were extensive and continuous, the wetlands in the wintering range were more like an archipelago. Much of the West Coast was too mountainous for extensive wetlands to form. Along the coast, fjords between Alaska and southern British Columbia were not conducive environments for the creation of wetlands. Waterfowl flying to wintering grounds beyond Alaska's Copper River Delta would not encounter another estuary of comparable size until they reached southwestern British Columbia. There, the Fraser River formed a large delta where the river entered the Georgia Strait. Birds congregated there, and at Sumas Lake sixty miles east of the delta. Marshes were also abundant on the Chilcotin Plateau in British Columbia's interior, but like the wetlands farther north, they were used by waterfowl only in the warmer months. In coastal areas, where the temperatures were mild, migrants could live in large numbers throughout the winter. Because of this, most British Columbia wetlands were primarily breeding and staging areas for birds that wintered to the south.14

The lowlands surrounding the Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound were also valuable habitat for migratory waterfowl. Bogs and marshes formed in the depressions left by retreating glaciers were common throughout the area. As in the far north, the river deltas were the most important areas for migrating ducks and geese. Largest among these was the Fraser River Delta, but the deltas of the Skagit, Duwamish, and Nisqually also attracted waterfowl. These lowlands were transitional areas for migratory waterfowl. Some species or populations of waterfowl ventured no farther and wintered in these sites. Others used them as staging sites before continuing on to other wintering areas. It was this mosaic of habitats that attracted the birds.15

Many large wetlands were found in the wide depressions of the Great Basin, a physiographic province encompassing most of Nevada as well as southeastern Oregon, western Utah, and southern Arizona. Without any natural outlet, the rivers flowing from the north-south trending mountains in the region drained into basins, where, over time, much of the water evaporated. In an environment with such high evaporation rates and no drainage, the remaining lake water became hypersaline. The Great Salt Lake in northern Utah was the largest of these lakes. Smaller lakes like Lake Abert in Oregon, Pyramid and Winnemucca lakes in Nevada, and Mono and Owens lakes in California were also important. These lakes were particularly valuable for non-waterfowl species like American avocets, snowy plovers, phalaropes, and eared grebes, which could tolerate the saline water and feed on the relatively small number of species living in the lakes. Most Great Basin lakes were too saline to support abundant wetlands, but extensive marshes could form where modest drainage occurred or when rivers emptied into the lakes. This was the case in the Malheur and Klamath Basins of central Oregon. In both areas, there was sufficient drainage to prevent lakes from developing salt levels that would inhibit wetland development.16

More than any other areas along the Pacific Flyway, the lakes and marshes of the Great Basin were subject to change that likely affected the distribution of waterfowl. During the Pleistocene, immense lakes such as Lake Modoc, Lake Lohontan, and Lake Bonneville connected most of the now-dry valleys.17 Over the past 12,000 years, the distribution and size of Great Basin lakes changed in response to the climate. Most of these lakes disappeared as the climate warmed, but between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago, many of the valleys within the Great Basin contained substantial marshes. Paleoecologists and geologists have found evidence of cattails and other marsh vegetation from that time in the Las Vegas Valley of southern Nevada. Scientists also believe that the marshes at Ruby Lake in central Nevada were deeper and more extensive than they are today. The bones of ducks and other wetland-dependent bird species found in the basin sediments from this period show that waterfowl used the area extensively. Presumably, other valleys in the Great Basin also had lakes...