![]()

CHAPTER 1

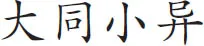

SIMILAR, WITH MINOR DIFFERENCES

A Tale of Two Villages

“Doing tourism” in Ping’an and Upper Jidao entails pragmatic and discursive understandings of both being an ethnic minority and being rural in China today.1 After all, the potential success of tourism in these communities rests upon their ability to turn a profit from the tourist’s experience of encountering ethnic difference in a visually and physically distinctive rural landscape. While similarities between many ethnic tourism destinations around the world speak to the standardizing effects of tourism as a commercial enterprise, studies of ethnic tourism often emphasize the role of national government policies and programs that direct and regulate ethnic encounters. This regulatory feature of ethnic tourism points to contestations over the governance of ethnic identity in contemporary nation-states, including China. For village residents who must do tourism, their identities as ethnic and rural are more than performative roles to be enacted in the presence of tourists; these subjectivities provide a moral understanding of the changes and conflicts experienced in each community over the past decades of socioeconomic transformation.

HAVE YOU LOST YOUR ETHNIC IDENTITY?

It took me a few months in Ping’an to work up the nerve to approach Lao, one of the elder leaders of the village, for an interview. Everyone said I needed to speak with him to get the whole story on how tourism started in the village. I was worried about not being taken seriously by someone so well respected within the village, even though I knew his family fairly well. Trained as a doctor, Lao was a Party cadre and had been privy to the first discussions on tourism in Ping’an in the late 1970s. He opened the village’s second guesthouse, named Li Qing after his two daughters, in the early 1990s. By the mid-2000s, Li Qing was a veritable brand-name enterprise by Ping’an standards, with three guesthouses and a steady stream of foreign and domestic customers.

The first time I asked Lao if he was willing to be interviewed, he said yes but he was busy that day; he suggested that I find him another time. Meanwhile, without my prompting, he wrote out the history of the village’s tourism development for me, and when I returned to interview him, he read the document aloud and I asked questions to clarify certain points.2 When he reached the end, I asked what he thought about the future of tourism in the village. Lao pointed out four problems that needed to be addressed: more equitable monetary compensation for villagers who worked on maintaining the terraced fields; more public infrastructure, such as village paths and toilets for tourists; better management of water resources; and treating tourists with greater respect. On this last point, Lao said that the Zhuang used to be known for their hospitality, generosity, and cleanliness, but over time, as a result of tourism, these “special characteristics” (tese) of the Zhuang were fading fast. This prompted me to ask, as I had started to do jokingly with some of my friends in the village, if Lao thought that the villagers had stopped “being Zhuang” as a result of tourism in Ping’an. Many scholars, journalists, and tourists write about this idea, I added—namely, that tourism is causing people to lose their ethnic identity. Did he agree? Without a moment’s pause, Lao responded, “No.”

He elaborated on his point a few days later, when I went back to his house to pick up a copy of his history of tourism development in Ping’an. He was at home with his wife and one of his grandsons. (During the week, Lao’s wife and grandson lived in the county seat, Longsheng, so that the grandchildren could attend primary school in town. They were back in Ping’an for a weekend visit.) Lao handed me a carefully rewritten copy of his account, and I looked through it. Then, Lao suddenly added that he had thought of something that had really changed in village life and affected their “folk customs” (minsu) since tourism had begun twenty-five years ago: the environment and sanitation in the village were much, much worse now than before, he declared.

Before a lot of tourism, Lao continued, the surroundings and the water in the village were “very lovely, very nice,” but with “development, and doing tourism, the garbage hasn’t been taken care of—the water in the ravines, streams . . . now you don’t even dare to wash your hands or feet [in that water]; the environment is really bad.” This was a matter of custom, he added, because the environment’s decline directly affected the life and the look of the village. “The original atmosphere, the original appearance [yuanfeng yuanmao] of the village has changed,” and he put part of the blame for this squarely on the villagers themselves. “The people’s habits are bad—human waste, sewage, animal waste, everything is dumped in the ravine” to flow down the mountainside to the river below. I suggested that perhaps it was the numbers of tourists who were contributing to the environmental problems, but Lao disagreed. To him, the problems of sanitation and the decline of the environment in Ping’an were the problems of the people who lived in Ping’an. The inference was clear: for the Zhuang, his community, to neglect the environment was a crisis rooted in the core of their consciousness as a people. To be Zhuang, Lao implied, was to take pride in the environment and thus to maintain its cleanliness; the degradation of the latter, therefore, was an indication of the decline of Zhuang identity itself. This was a comment not only on individual behavior and bad decisions; this was a matter of their collective, shared identity as a part of the Zhuang ethnic group.

My initial surprise at the apparent disconnect between the changes Lao associated with ethnic identity in the village and what I assumed to be “ethnic” reveals both the wide applicability of the term “ethnic” to describe myriad human behaviors and attributes and the specificity and the seriousness of these claims. When I joked about “losing your ethnic identity” with others in Ping’an, the only concrete aspect of Zhuang life that we usually agreed was being “lost” was knowledge of the Zhuang language among younger generations. The children now spoke standard Chinese (Mandarin, putonghua) in school and in their interactions with tourists; some children even preferred to use standard Chinese instead of the local, regional dialect (called Guilinhua, named after the nearest major city).3 Historically, language provided a recognized “boundary” (following Barth 1969) between the ethnic identities of the tourists (who generally were not Zhuang or did not know the northern dialect of Zhuang spoken in Ping’an) and the village residents.4 How was sanitation and the treatment of wastewater somehow also an ethnic characteristic, or at least tied to local senses of collective community and belonging, as Lao seemed to suggest?

Ethnic tourism has been defined as a type of tourism “marketed to the public in terms of the ‘quaint’ customs of indigenous and often exotic peoples . . . [including] visits to native homes and villages, observation of dances and ceremonies, and shopping for primitive wares and curios” (Smith 1989 [1977], 4). “As long as the flow of visitors is sporadic and small,” Valene Smith (ibid., 4) has written, “host-guest impact is minimal.” However, Ping’an received more than two hundred thousand visitors in 2006, and by resident reports the numbers have continued to increase since; for a village of approximately 850 regular residents, the impact of this many tourists can hardly be minimal. Lao’s concern over the environment in Ping’an tied his worries about the effects of environmental degradation to the material, cultural lives of village residents and to the ways in which the Zhuang would be perceived by national and international visitors. In his assessment, the problems boiled down to ethnicity. He was proud of being Zhuang but disappointed in the community’s behavior that reflected poorly on their collective identity. After all, Ping’an was a Zhuang village—it said so in all of the tourism brochures and on a sign at the entrance to the village. Beyond the importance of maintaining pride in one’s own community, even more pressing at the time was the fact that in response to greater market competition from other tourism villages in the region, Ping’an residents themselves were actively trying to make the place more “ethnic” for tourists.

Lao’s perspective on Zhuang ethnicity revealed both a local understanding of ethnic identity that diverged from dominant national discourses of ethnic minorities (shaoshu minzu) and a cautious eye to the demands and requirements of the current politics of tourism and development. “Sanitation” and “cleanliness” are keywords of rural tourism and rural development more generally, and by linking Zhuang identity to the imperative to be clean, Lao in turn reaffirmed the significance of Zhuang ethnicity to both a personal, subjective sense of self and belonging to this place and to the broader imperatives of the national tourism marketplace. The codification of ethnicity in contemporary postreform China, particularly in cultural productions and place-based naming strategies, has marked the ethnic as a particular type of commodified characteristic within the greater national narrative of China’s development since the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949.5 These techniques and stereotypes are fully exploited in tourism today.

MAKING SHAOSHU MINZU

While studies of tourism often emphasize the appeal of the ethnic “Other” as a factor in tourist motivations, the institutional state history of ethnic classification and minority identity in China requires a closer examination of the relationships between ethnicity and national modernization policies (Sautman 1999), how the state has constructed ethnic difference, and how these relate to the ways ethnicity is used in Chinese tourism. Two interlocking aspects of ethnic identity construction and representation frame the circumstances now faced by rural ethnic tourism villages. First, early discourses of non-Chinese populations within the Chinese imperial imagination informed modern nationalist sentiments in China, most notably during the establishment of the Republican government in the early twentieth century. Second, the Ethnic Classification project (minzu shibie) of the 1950s and 1960s began the process of formally determining the number, boundaries, and characteristics of the ethnic minority groups recognized by the Chinese Communist state.6 The inherent difficulty of such a project, and the complexities involved in determining a finite number of ethnicities, are visually illustrated in documentary and feature films of the 1950s and 1960s that depict ethnic minorities. In these films, ethnicity was made visually knowable and recognizable, as the country’s forward-looking development was rendered into visual narrative form. This emphasis on the visible evidence of ethnicity and modernization has left lingering traces on how tourism development in rural ethnic minority regions is expected to unfold and ultimately succeed.

Concern over, or at least an expressed interest in, the non-Chinese populations at the borders of the Chinese empire has been recorded since as early as the first century BCE, in the Records of the Historian, by Sima Qian (Harrell 2001, 36). The mythology of barbarian tribes occupying the empire’s edges and borderlands was also a feature of a Confucian worldview (Dikötter 1992, 2–7). Notions of classification and identification already existed in imperial records, and embedded in these writings were politically driven ideas of barbarian populations as capable of being “transformed” or becoming “Chinese” (hanhua) (Dikötter 1992 and Leibold 2007).7 Visual representations were significant as a tool for classifying and knowing difference. Ethnological reporting in the Ming and Qing dynasties generally appeared in one of two genre forms: gazetteer accounts or pictorial descriptions, such as the “Miao Albums.”8

During the late Qing dynasty, the growing presence and activities of Western missionaries in China also contributed to conceptualizations of race, drawn from Western theories of racial types.9 In southwestern China especially, Western missionaries working in Guizhou and Yunnan recorded their own tribal classifications of the local populations (see Clarke 1911) while adding to local understandings of group identity during this tumultuous period of imperial decline and revolution (Cheung 1995 and Swain 1995). The effects of these discursive changes were extensive and deep. By the late nineteenth century, challenges to the Qing empire increasingly began to be formulated in racialized terms.10 The term minzu first appeared in China around 1895, as a Chinese pronunciation of the Japanese minzoku. Minzu was first used to refer to the majority Han people, as opposed all other minority groups, and later, by extension, to the notion of a Han nation-state in the Republican era (Y. Zhang 1997, 76), glossed by Sun Yat-sen’s principle of nationalism (minzu zhuyi).11

Minzu zhuyi was an inclusive discourse of racial amalgamation, small in scale yet large in scope, in which, according to Sun Yat-sen, the new Chinese Republic would unite the Han, Manchu, Mongol, Hui, and Tibetan territories, subsequently uniting these five races into a single people (Leibold 2007, 38). Not surprisingly, these five races were associated with the territorial boundaries of the new Chinese Republic. As a result, discourses of minzu shifted from relating to notions of the nation-state, in the political sense of autonomous rule and governance, to concepts of ethnicity and identity, rooted in shared social traits and histories (Y. Zhang 1997, 76). These pre-Communist strategies of knowing and classifying ethnic difference in the modern Chinese nation-state deeply informed the policies of the early Chinese Communist government (Harrell 2001, 37; and Mullaney 2004a and 2011).

The Chinese Communist Party was concerned with ensuring the unity of the nation while representing the new nation-state as one founded on the will of people. The granting of autonomy to regions inhabited by ethnic minorities—a decision included in Communist policies before the People’s Republic of China was formally established in October 1949—meant only that “in regions where one ethnic group exercised autonomy, a member of that group should head the [local] government” (Mackerras 2004, 304–5; see also Heberer 1989). By 1953, the plan to develop People’s Congresses at national, provincial, county, and local levels with one representative from each minority group in the National People’s Congress meant that a limited number of minority groups was needed to construct the congress. However, censuses taken between 1953 and 1954 under an original policy that allowed groups to self-identity and self-name produced more than four hundred different ethnic group names nationwide (Fei 1981, 64; and Schein 2000, 81).12

To determine a more manageable number, at least in terms of the composition of the National People’s Congress, linguists and social science researchers were commissioned to identify and classify the various ethnic minority groups within China’s political borders in the campaign known as the Ethnic Classification project. The 1956 text of the drafted policy on national minorities and the “national question” (Moseley 1966) revealed the careful and deliberate movements of the young Chinese Communist Party government toward shifting the significance of minzu from nationality, and its possible corollary of nationhood for minority groups within China, tow...