- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

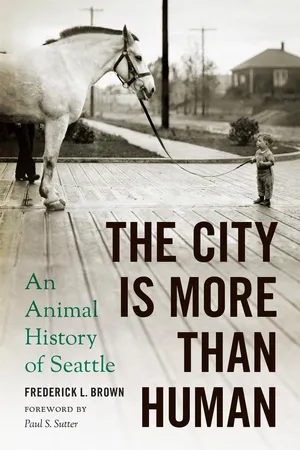

Winner of the 2017 Virginia Marie Folkins Award, Association of King County Historical Organizations (AKCHO) Winner of the 2017 Hal K. Rothman Book Prize, Western History Association Seattle would not exist without animals. Animals have played a vital role in shaping the city from its founding amid existing indigenous towns in the mid-nineteenth century to the livestock-friendly town of the late nineteenth century to the pet-friendly, livestock-averse modern city. When newcomers first arrived in the 1850s, they hastened to assemble the familiar cohort of cattle, horses, pigs, chickens, and other animals that defined European agriculture. This, in turn, contributed to the dispossession of the Native residents of the area. However, just as various animals were used to create a Euro-American city, the elimination of these same animals from Seattle was key to the creation of the new middle-class neighborhoods of the twentieth century. As dogs and cats came to symbolize home and family, Seattleites' relationship with livestock became distant and exploitative, demonstrating the deep social contradictions that characterize the modern American metropolis. Throughout Seattle's history, people have sorted animals into categories and into places as a way of asserting power over animals, other people, and property. In The City Is More Than Human, Frederick Brown explores the dynamic, troubled relationship humans have with animals. In so doing he challenges us to acknowledge the role of animals of all sorts in the making and remaking of cities.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword: The Animal Turn in Urban History

- Introduction

- One Beavers, Cougars, and Cattle: Constructing the Town and the Wilderness

- Two Cows: Closing the Grazing Commons

- Three Horses: The Rise and Decline of Urban Equine Workers

- Four Dogs and Cats: Loving Pets in Urban Homes

- Five Cattle, Pigs, Chickens, and Salmon: Eating Animals on Urban Plates

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Methodology

- List of Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index