![]()

CHAPTER 1

WATER HAZARDS

THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER surges around the sweeping crescent that gives New Orleans its nickname and into a sharp bend at the foot of Jackson Square. Even at low stage, the river’ width is considerable in comparison with European waterways that were known to colonial explorers and settlers. When the river rises above its banks, its size becomes even more impressive. In the early eighteenth century, floodwaters could spread out over several miles on either side of the mighty stream, destroying spring crops and ruining homes. The floods of the lower Mississippi were destructive by shallow immersion, not due to a torrential current. A thin veneer of water could spread over the countryside, stand on the fields for several months, and drown young plants. Floodwaters also crept into houses, softening their foundations, transformed firm roadways into quagmires, and interrupted urban life for extended periods of time. French colonial leaders recognized these hazards, and they debated the viability of the site that became New Orleans before reluctantly deciding to plant the capital there.1

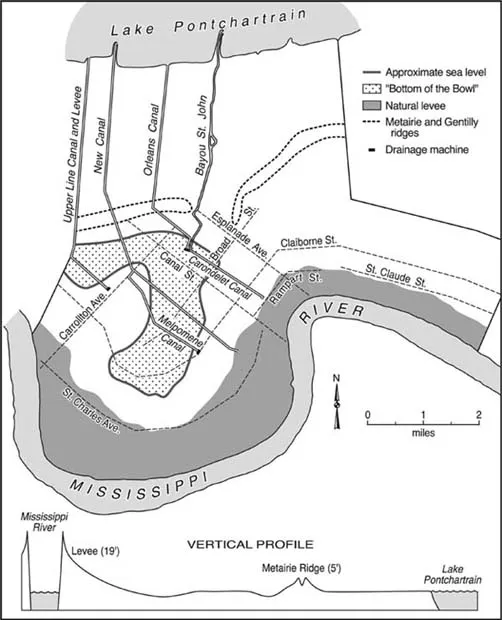

The geography of flood hazards is not the same in all locations, and the topography of New Orleans was, in many respects, the reverse of what settlers were accustomed to. Rather than a broad concave valley with safely elevated settlement sites on land that rose with greater distance from the waterway, the Mississippi delta was a nearly level surface, with subtle but significant topographic undulations. The river built the land with its frequent inundations, and thus New Orleans’ original plan occupied a tract subject to regular flooding. The high ground was not set back from the river but consisted of only the relatively narrow natural levee. The crests of the high ground stood only about 12 feet above sea level. The batture, or actual river bank, dipped into the waterway, while the back side of the natural levee followed an invisibly gentle gradient in the other direction. Most of the city naturally drains away from the river. Less danger existed atop the elevated and better-drained natural levee (Fig. 1.1), where French settlers built New Orleans and where most of the city stood in 1800. Although subject to seasonal inundation, the ridge that paralleled the river was the last land to go under water and the first to emerge from receding floods. Indeed most flooding occurred when crevasses, or breaches in the natural levee and later the artificial levees, allowed water to break through the higher terrain and flow directly to the low ground farther from the river.

Areas to the rear, or away from the natural levees, remained under water longer and formed the cypress swamps draped with Spanish moss. These dark, foreboding wetlands harbored not only alligators and clouds of mosquitoes but the mysterious and dreaded miasmas. In the minds of nineteenth-century residents, the swamp and its pestilential emissions posed as much of a hazard as the river to those dwelling in New Orleans. Efforts to control flooding concurrently sought to eliminate the backswamps as a source of disease. William Darby’ 1817 geography of Louisiana stated: “It must be observed, that there are two evils, arising from surplus water, to be remedied on the Mississippi; one, the incumbent waters in the river; the other the reflux from the swamps. It is in most instances very difficult to remove one inconvenience, without producing the opposite.”2 Floodwaters contributed to the moist conditions of the backswamp, and thus the two threats were thoroughly mixed. Efforts to control one, as Darby pointed out, often exacerbated the other.

Geographers portray the realm of human-environment interaction as a two-sided process. Relations with positive outcomes define resources, while negative results constitute hazards. The river and backswamps in and around nineteenth-century New Orleans represent both sides of this connection, and thus the human-environment perspective is useful for beginning our discussion. As resources, the river served as a vital communication link, and the swamps provided durable cypress timber. At the same time, the waterway and the wetlands posed undeniable hazards to lower river valley residents. This chapter will examine the hazards side of the human-environment relationship. Dealing with hazards involved appraising them, creating plans to contend with them, implementing these plans, and then maintaining the means used to defend against unwanted environmental conditions. Preparing for and responding to water hazards were powerful influences in shaping the largest city on the lower Mississippi. While flood and environmental disease were only two of many hazards, they were perhaps the most frequently discussed and also prompted the most sweeping transformations of New Orleans’ environs. These manipulations were the measure of transactions between humans and nature.3

FIG. 1.1. TOPOGRAPHY OF NEW ORLEANS, CA. 1900. The natural levees formed the best-drained and highest ground, while the Metairie and Gentilly ridges provided secondary bands of high ground. The natural levee sloped from the river to a flood-prone area below sea level, riverward of the Metairie Ridge. From the narrow ridge, land sloped to sea level and Lake Pontchartrain.

CONFINING THE RIVER

By 1800 the two prominent hazards at New Orleans had elicited significant human response. The French reaction to floods was to erect levees (from the French word lever, “to raise”), ridges of soil heaped up along the natural high ground to hold back high waters. In the urban setting, where the concentration of people and public buildings was greatest, the corporate sponsor, the Company of the Indies, initially took on the levee-building responsibility. In other words, the initial protection device was a public project and not financed by private landowners. By 1727 a bulwark 4 feet high stretched about a mile along the waterfront, on top of the natural levee. However, isolated stretches of levees did not keep high water from finding its way to the backswamps upstream or downstream from the protected territory. Since the natural levee sloped back from the river over 10 feet to the city’ low point, high water that escaped the river upstream from the city could rise from the back side. Consequently New Orleans continued to endure back-swamp flooding on a regular basis, and occasionally floods would crest the 4-foot mound along the waterfront. Company of the Indies officials understood the settlement’ topographic situation and constructed a pair of levees perpendicular to the river that extended toward the backswamp. Another levee, along the current route of Rampart Street and roughly parallel with the riverfront bulwark, tied the levees together and completed the enclosure. This first levee system enclosed a mere forty-four square block area. Although it fended off most high water, the most formidable levee in the valley collapsed before the 1735 flood, and the city suffered extensive damage.4 Despite such failures, efforts to protect the colonial capital remained a centralized function. Through the Spanish rule of the Louisiana colony, public funds underwrote the urban levee system’ maintenance.5 This underscores the obvious importance of the city to the colony and exhibits the public, as opposed to private, responsibility for shielding the urban population and property from floods. This practice set the city apart from the rural countryside in terms of both policy and protection.

Coordination with its expanding agricultural hinterland was necessary to effect a viable flood protection barrier for New Orleans. To guard the growing agricultural district and link rural levees with the urban bulwark, colonial laws enacted in 1728 and in 1743 required individual landowners to build levees—a type of labor requirement that did not exist in the city.6 In effect, the second thrust of urban environmental change was the requirement that rural property owners build their own levees that would contribute to New Orleans’ protection. The city’ economic success depended on a thriving agricultural hinterland, and without adequate flood protection neither city nor hinterland could survive. The French long-lot, or ar-pent, survey system arranged individual holdings in narrow parcels of land stretching back some distance from the river and suited the private levee-building requirement well. Individual grants typically ranged from 2 to 8 arpents (384 to 1,536 feet) in width and were usually 40 arpents (7,680 feet) deep. Proprietors were thus responsible for constructing levees along their property’ short axis. By dispensing grants in contiguous parcels, French authorities sought to encourage a continuous line of levees fronting the agricultural “coast,” but this goal was never realized. Levee construction became a sizable investment for landowners and was only feasible for wealthy planters using slave labor. Consequently, most small landholders were unable to complete their protective structures. Although even wealthy planters may have been reluctant to make such a large investment, the threat of confiscation for failure to comply motivated most to participate—to some extent. When Spain took over the colony in 1768, the Spanish government seized on the precedent established by the French, continuing to encourage contiguous settlement and also requiring landowners to construct protective barriers against floods.7

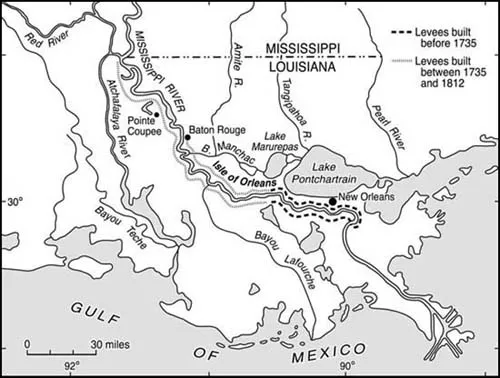

Despite a sound policy, privately built structures were notoriously inconsistent in design and effectiveness, and floods continued to breach these ever-lengthening earthen embankments. Nonetheless, levees stretched along about 50 miles of riverfront above New Orleans by 1763.8 The leveed territory served as the productive agricultural base for the port of New Orleans, while the unprotected territory remained subject to inundation. When the new U.S. territory of Louisiana passed its first levee law in 1807, it assigned authority for maintaining levees to the parishes, which in turn held rural landowners accountable—perpetuating traditional landowner responsibility.9 When Louisiana became a state in 1812, levees paralleled the Mississippi River from almost as far as the mouth of the Red River to below New Orleans on the west bank and from the bluff at Baton Rouge to below New Orleans on the east bank (Fig. 1.2).10 But without an overarching design and in the absence of a central flood protection authority, levees continued to present a piecemeal barrier and offered only erratic effectiveness.

FIG. 1.2. LEVEE DEVELOPMENT TO 1812. Levees stretched several miles up the river by the mid-eighteenth century and nearly to the mouth of the Red River by the early 1800s. After Albert E. Cowdrey, Land’ End: A History of the New Orleans District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and Its Lifelong Battle with the Lower Mississippi and Other Rivers Wending Their Way to Sea (New Orleans: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1977).

New Orleans, by contrast, continued to maintain its municipal levees after it became a U.S. possession. To fund this ongoing project, it taxed watercraft tied up along its waterfront. In 1805 the Conseil de Ville issued a resolution that read: “considering that the levees are being constantly damaged by the ships, lighters, boats, etc. that land and stay in the port of the city, and that it is quite justifiable to make them contribute to the expenses occasioned by the considerable damages they cause daily and whose repair has been, up to the public chest.”11

This resolution replaced a preexisting anchorage assessment with a levee tax that set up a fee schedule and assigned an individual to collect the taxes. Owners of vessels weighing more than 100 tons paid up to $40, while owners of craft weighing less than 100 tons paid $12. Flatboats, keel boats, and rafts of timber were charged from $3 to $6 for the privilege of tying up alongside the city’ levee. In 1819, the city collected over $12,000 for levee maintenance with this tax.12 Thus the city passed a share of the cost of maintaining its desperately needed levees on to transient shippers while maintaining local control of construction and maintenance. Indeed, when the U.S. Congress questioned New Orleans’ authority to collect a tax on what was considered federal property, the city council sent a strong resolution to Washington claiming that “it is an established fact that the Port of New Orleans would not exist, that the whole city would soon be submerged if the waters of the Mississippi were not confined by levees.” It concluded with the assertion that “the existence of this tax is therefore indispensable for the maintenance of the Port of New Orleans.”13

It was apparent by the early 1800s that levees, while essential, did not eliminate the flood hazard. One reason for their ineffectiveness was that levees displaced high water into unprotected territory. As New Orleans raised barriers along its waterfront, the need for levees outside the city increased. Flood protection in one location redirected risk to open floodplains elsewhere. By necessity, levee building proceeded up and down the river and along both banks. The priority of protecting the city propelled similar action in the countryside.

William Darby pointed out a second reason for the levees’ limited effectiveness in his 1817 geography: “The confined body of water increased in height.”14 As the width of the floodplain available to the river was restricted, the same volume of water reached higher stages. In other words, the levees raised the flood level. As levee construction extended along more and more of the banks, the area open to high water decreased, further heightening the flood stages. Consequently, society on the lower river faced a continual struggle to raise the levees in order to offset the higher flood stages they created. The prevailing policy exacerbated the growing flooding problem and may have contributed to the massive flood of 1785, which inundated New Orleans and much of the lower valley.15 By the early nineteenth century, the 4-foot levees fronting New Orleans had been raised to about 6 feet to compensate for the rising flood stages.16 The city surveyor oversaw this effort and used chain-gang labor to maintain the protective barrier.17 Levees remained the only realistic option. Under a policy that called for localized (city or individual plantation) flood protection, there could be no coordinated regional planning. Neither state nor federal governments were ready to step in at the time. Although people along the river understood the implications of levee building, no one had the wherewithal to do anything more than heap up a mound of dirt in between their property and the river and hope for the best.

Even as protective devices displaced some of the risk, the rising crests continued to threaten New Orleans. After a pair of urban inundations in the late Spanish occupation (1791 and 1799), sizable floods occurred in rapid succession during the early American period. High water in the lower valley threatened the piecemeal levee system in 1809, 1811, 1813, 1815, 1816, and 1817. During that spell of successive floods, the New Orleans city council passed an ordinance that made individual landowners responsible for building and maintaining levees within the “liberties” of New Orleans—or the urban fringe. Much like the territorial law of 1807, the municipal ordinance called on proprietors to construct levees at least one foot higher than the “highest swell.” By doing so, it sought to enforce a more consistent level of protection and placed the cost on those living outside the more densely built-up urban territory. To ensure compliance, the ordinance empowered the mayor to have the work inspected and to order contractors to complete any unsatisfactory sections at the owner’ expense.18 This ordinance shifted a portion of the city’ burden to those who lived within Orleans Parish but beyond the city limits. Like the territorial laws that applied to other parishes, it functioned to protect the city.

Despite great efforts to create impenetrable barriers, contemporary accounts highlight obvious failings of the antebellum levees. Henry Bracken-ridge, who visited the city in the early years of statehood, provided some of the most extensive descriptions of the levees as they existed at that time. He noted that landowners set them back from the river about 30 to 40 yards—seeking to prevent undercutting by the meandering river, while not sacrificing too much agricultural land. The preferred construction material was a stiff clay, which provided a more effective waterproof barrier. Once the 4- to 6-foot-high levees were in place, builders added sod to prevent erosion and cypress slabs to the inside to prev...