![]()

PART I

RUNNING UPSTREAM

“Our number-one objective in this life must be to find common ground.… It does us no good to forge forward in the struggle to survive if we forget that we must all fit in the same canoe. We share this land. We share these resources. We share a common future.… Our customs and traditions may not fit into the same molds that Western society embraces, but that doesn’t make them wrong. It makes them different. If we are to paddle the river of life together, we must all learn to understand, appreciate, and, yes, celebrate these differences.”

—Billy Frank Jr. (Nisqually)

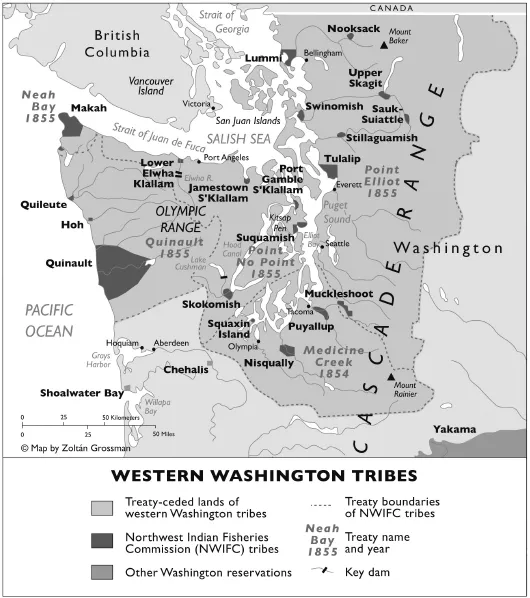

THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST IS OFTEN CONSIDERED THE PROTOTYPE for conflicts between Native nations and non-Indians over tribal treaty rights to natural resources. Before colonization, tribes along the Pacific coast and Salish Sea had direct access to plentiful salmon, shellfish, and other marine species, and tribes in the semi-arid Plateau region east of the Cascades harvested salmon that migrated into the interior through the Columbia River.

In the 1850s, as full-scale American settlement began in the Pacific Northwest, Washington Territory governor Isaac Stevens negotiated a series of six treaties with the Native nations of what would later become Washington State and parts of Oregon and Idaho. In order to survive on new reservations, and maintain their ancient resource-based cultures, the Native nations signed the treaties only on the condition that they would retain their preexisting rights to fish, hunt, and gather shellfish and plants in their treaty-ceded territories. As the territories were admitted to the Union, state and federal governments restricted tribal fishing in violation of the treaties.

The tribal fishers’ reassertion of treaty rights in the 1950s and 1960s set them on a collision course with state government, white sportfishers, and the commercial fishing industry, resulting in numerous violent clashes over two decades. Treaty rights leaders such as Billy Frank Jr. and Joe DeLaCruz repeatedly risked arrest on the rivers in order to fish. Beginning in the 1970s, Northwest anti-treaty movements (and politicians such as Slade Gorton) served as a template for the “white backlash” to Native sovereignty elsewhere in the country. Likewise, federal court decisions to uphold treaty rights (notably the 1974 Boldt Decision), and resulting programs to cooperatively protect fish habitat, have served as a model for other parts of Indian Country.

Since the 1980s, treaties have had profound and lasting implications for landownership and resource politics in the entire region. The tribes have developed their own commercial fishing fleets, sustainable timber and game management, and gaming operations. Non-Indian society has experienced a dramatic transition from an extractive economy based on logging and fishing to a heavily urbanized and high-tech economy. In a dramatic turnaround, a few of the sportfishing and commercial fishing leaders who had opposed treaty rights gradually came to recognize the treaties’ power in protecting the fishery from harmful development and in preventing the regional extinction of salmon.

Salmon are not only a delicious food but also a sacred being to Native peoples, an economic keystone for fishing communities, and the key “indicator species” for the health of the entire ecosystem. Salmon survival is affected by the “four H’s”: harvest of the fish population, hatcheries to enhance the population, hydropower dams that block fish migration, and habitat threatened from logging, agriculture, urbanization, and other development. Simply because of the multifaceted threats to the survival of endangered salmon, protecting fish habitat involves not just a few environmental reforms here and there but a revolutionary overhaul of environmental policies.

The Pacific Northwest case studies examine the Native/non-Native relationship in the harvest and protection of natural wealth and in the common purpose of protecting salmon. But the larger question is how place-based conflict is best managed or resolved. Is it more effective to build a common sense of understanding from the top down, using “government-to-government” cooperation and a common state citizenship as the starting point? Or is it more effective to lessen conflict from the bottom up, using “people-to-people” cooperation and a common sense of belonging to a place? Are these approaches mutually exclusive, or can they somehow be combined or interwoven? If a common “sense of place” can be constructed by an alliance, at what scale is it most effective? Can people wrap their heads around a vast region of river basins and mountains, or is their love for a local watershed the best place to start?

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Fish Wars and Co-Management

Western Washington

THE TRIBES OF WESTERN WASHINGTON ARE CLUSTERED AROUND THE mouths of rivers that lead into Puget Sound and the Hood Canal (the southern inlets of the Salish Sea) and the Pacific Ocean.1 Colonization disrupted their Indigenous cultural and socio-economic systems that had remained resilient for many centuries, through fishing, hunting of game, and gathering of plant foods and medicines in vast territories.2

In 1854 and 1855, Washington territorial governor Isaac Stevens, also the superintendent of Indian affairs, negotiated a series of treaties with the Native nations of western Washington and the Columbia Basin, to open the land for American settlement and clear land title for a planned transcontinental railroad to Puget Sound. The treaties extinguished Native claims to 64 million acres of land, in return for the exclusive tribal use of reservations totaling 6 million acres, on some of the region’s major rivers.3 The treaties ceded nearly all the land of the region, limiting the tribes to reservations, but also allowed the tribes to retain access to the rich salmon fisheries of the Pacific Coast and Salish Sea.4

The 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek was typical of these treaties, in stating that the right to fish in “all usual and accustomed fishing grounds and stations, is further secured to said Indians in common with the citizens of the territory … together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries” inside and outside of their new reservations.5 The treaties defined the relationship between the federal government and up to twenty-two treaty tribes in western Washington, particularly in the “usual and accustomed” areas around the mouths of rivers, where the tribes exercised their “usufruct” (use) rights to harvest the fish even if they no longer owned the land.6 As Governor Stevens promised the tribal leaders, “This paper secures your fish.”7

After the treaties were signed, it became clear to the Nisqually, the Puyallup, and some other tribes that the tiny reservations chosen for them by Stevens would constrict their access to their fishing and gathering grounds. They hoped to gain access to larger and better-situated lands, in order to survive. The intransigent Stevens’s refusal helped spark the Puget Sound War of 1855–56. Settler vigilantes, backed by Stevens, formed “Volunteer” militias that massacred Native civilians, drawing criticism from other settlers for provoking Native resistance.8 A notorious 1856 massacre, for example, targeted Nisqually men, women, and children at the confluence of the Nisqually and Mashel Rivers.9

A number of settlers around Nisqually, including some who had been employed by the Hudson Bay Company and had become kin to Native families, allegedly gave shelter and supplies to the fighters led by Chief Leschi, a key figure in the revolt. Stevens put five of these settlers (known as the Muck Creek Five) on trial.10 But the prosecutions were unsuccessful, and in an 1856 agreement the Nisqually and the Puyallup won access to larger reservations on their mainstem rivers, closer to their “usual and accustomed” fishing grounds, as well as prairies for root digging and horse pasture. Chief Leschi was executed in 1858 for the “murder” of a militia officer. Understanding that Leschi’s action was legal during the war, the army refused to allow the execution within its fort.11

Salmon harvest allocation was not a concern in the rich Puget Sound fishery until the tin can came into common use in the 1880s and the first few canneries opened. Soon after Washington entered the Union in 1889, the new state government began to break provisions of the six treaties. Mechanization and rail access enlarged the commercial fishing industry, and salmon stocks began to become seriously depleted. In the meantime, the exploding non-Indian population took the prime fishing sites, and the state closed them off to tribal members, in the process racializing harvest locations and allocation.12

Tribal fishers traditionally harvested salmon with nets at river mouths, but the state government gradually outlawed the nets. Tribes could no longer fish in their “usual and accustomed” places; moreover, the available salmon were harvested by non-Indians before they could return to the treaty fishing grounds. As treaty researcher and activist Hank Adams has observed, “State laws prohibited them from fishing at sites off the reservations, or in the general non-Indian fisheries located any place more distant than five miles away from their particular reservation.”13 State agencies viewed tribal members as subject to state fishing regulations, in the interest of “conservation.” Through the early twentieth century, the tribal fishing economy collapsed and the tribes fell into poverty.14 The ancient fishing cultures struggled to survive, with fishers forced to operate underground for decades.

The tribes finally began to transform the same treaties that had dispossessed their lands into tools for exercising the usufruct rights they had retained to fish and gather. In the 1950s and early 1960s, small groups of tribal fishers took their boats and nets onto the rivers and estuaries of western Washington. State officials described them as “poachers” and “renegades” and blamed them for declining fish numbers, even as the non-Indian sport and commercial harvest levels skyrocketed.15 Yet even as public controversy raged around treaty fishing, the tribes never took more than 5 percent of the salmon harvest.16

THE “FISH-INS”

The first treaty rights cases were brought in the early 1950s by returning Korean War veterans, such as Billy Frank Jr. from Nisqually and Joseph (Joe) DeLaCruz from Quinault. Dissatisfied with negative or limited treaty rights rulings from state courts, tribes and fishing rights activists began to turn to the federal courts in 1954, when Puyallup treaty fishers Robert Satiacum and James Young were cited for steelhead netting in the Puyallup River at Tacoma.17

By the early 1960s, the Native activism had stimulated an intense and often violent backlash among non-Native fishers, who cut nets, pushed boats into rivers, and stole fish from tribal nets and traps. Native fishers often came under sniper fire or were threatened with firearms. In 1963, Tulalip treaty rights leader Janet McCloud organized a pro-treaty rally at the state capitol in Olympia, galvanizing the treaty rights movement and gathering non-Indian supporters.18

Inspired by the civil rights “sit-ins” of the era, tribal activists organized “fish-ins” and openly fished in front of state police and wardens as a form of nonviolent civil disobedience. Police and wardens would often raid the rivers, using boats and surveillance planes, to confiscate Native boats, equipment, and fish, and fine or jail Native fishers. Police would also ram and confiscate boats and tackle Native fishers.19

Among the tribal activists on the Nisqually River were Billy Frank Jr. and Sioux-Assiniboine researcher-organizer Hank Adams.20 Frank recalled the state police response to the fish-ins by Frank’s Landing: “We’d fish at night, get up early in the morning and take our nets out.… They’d steal our nets, and steal us, take us to jail.… We could get these guys to fight us at th...