- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

To most people, technology has been reduced to computers, consumer goods, and military weapons; we speak of "technological progress" in terms of RAM and CD-ROMs and the flatness of our television screens. In Human-Built World, thankfully, Thomas Hughes restores to technology the conceptual richness and depth it deserves by chronicling the ideas about technology expressed by influential Western thinkers who not only understood its multifaceted character but who also explored its creative potential.

Hughes draws on an enormous range of literature, art, and architecture to explore what technology has brought to society and culture, and to explain how we might begin to develop an "ecotechnology" that works with, not against, ecological systems. From the "Creator" model of development of the sixteenth century to the "big science" of the 1940s and 1950s to the architecture of Frank Gehry, Hughes nimbly charts the myriad ways that technology has been woven into the social and cultural fabric of different eras and the promises and problems it has offered. Thomas Jefferson, for instance, optimistically hoped that technology could be combined with nature to create an Edenic environment; Lewis Mumford, two centuries later, warned of the increasing mechanization of American life.

Such divergent views, Hughes shows, have existed side by side, demonstrating the fundamental idea that "in its variety, technology is full of contradictions, laden with human folly, saved by occasional benign deeds, and rich with unintended consequences." In Human-Built World, he offers the highly engaging history of these contradictions, follies, and consequences, a history that resurrects technology, rightfully, as more than gadgetry; it is in fact no less than an embodiment of human values.

Hughes draws on an enormous range of literature, art, and architecture to explore what technology has brought to society and culture, and to explain how we might begin to develop an "ecotechnology" that works with, not against, ecological systems. From the "Creator" model of development of the sixteenth century to the "big science" of the 1940s and 1950s to the architecture of Frank Gehry, Hughes nimbly charts the myriad ways that technology has been woven into the social and cultural fabric of different eras and the promises and problems it has offered. Thomas Jefferson, for instance, optimistically hoped that technology could be combined with nature to create an Edenic environment; Lewis Mumford, two centuries later, warned of the increasing mechanization of American life.

Such divergent views, Hughes shows, have existed side by side, demonstrating the fundamental idea that "in its variety, technology is full of contradictions, laden with human folly, saved by occasional benign deeds, and rich with unintended consequences." In Human-Built World, he offers the highly engaging history of these contradictions, follies, and consequences, a history that resurrects technology, rightfully, as more than gadgetry; it is in fact no less than an embodiment of human values.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Human-Built World by Thomas P. Hughes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Engineering General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2005Print ISBN

9780226359342, 9780226359335eBook ISBN

9780226120669CHAPTER ONE

Introduction: Complex Technology

Technology is messy and complex. It is difficult to define and to understand. In its variety, it is full of contradictions, laden with human folly, saved by occasional benign deeds, and rich with unintended consequences. Yet today most people in the industrialized world reduce technology’s complexity, ignore its contradictions, and see it as little more than gadgets and as a handmaiden of commercial capitalism and the military. Too often, technology is narrowly equated with computers and the Internet, which are mistakenly assumed to have been invented and developed in a private-enterprise market context. Having cultivated technology impressively, Americans, especially, need to understand its complex and varied character in order to use it more effectively as means to a wide variety of ends. Both the Flying Fortresses of World War II and the flying buttresses of the Middle Ages are technological artifacts.

In the following chapters, I draw upon and summarize the ideas of public intellectuals, historians, social scientists, engineers, natural scientists, artists, and architects who have helped me over five decades to better understand the complexity of technology and its multiple uses. Because the series in which this book appears is about science, technology, and culture, I also include descriptions of the works of artists and architects who have influenced my view of technology.

Since most of the works considered were done decades, even centuries, ago, they provide a historical perspective. This helps me and I hope my readers to move out of our present mind-set and consider the different ways in which technology has been envisioned as a means to solve problems, some different, some resembling those we face today. History does not repeat itself in detail, but drawing analogies between past and present allows us to see similarities. For this reason, generals study military history, diplomats the history of foreign affairs, and politicians recall past campaigns. As creatures in a human-built world, we should better understand its evolution.

Defining Technology

Defining technology in its complexity is as difficult as grasping the essence of politics. Few experienced politicians and political scientists attempt to define politics. Few experienced practitioners, historians, and social scientists try to inclusively define technology. Usually, technology and politics are defined by countless examples taken from the present and past. In the case of technology, it is usually presented in a context of usage, such as communications, transportation, energy, or production.

The word “technology” came into common use during the twentieth century, especially after World War II. Before then, the “practical arts,” “applied science,” and “engineering” were commonly used to designate what today is usually called technology. The Oxford English Dictionary finds the word “technology” being used as early as the seventeenth century, but then mostly to designate a discourse or treatise on the industrial or practical arts. In the nineteenth century, it designated the practical arts collectively.

In 1831 Jacob Bigelow, a Harvard professor, used the word in the title of his book Elements of Technology . . . on the Application of the Sciences to the Useful Arts. He remarked that the word could be found in some older dictionaries and was beginning to be used by practical men. He used “technology” and the “practical arts” almost interchangeably, but distinguished them by associating technology with the application of science to the practical, or useful, arts. For him, technology involved not only artifacts, but also the processes that bring them into being. These processes involve invention and human ingenuity. In contrast, for Bigelow, the sciences consisted of discovered principles, ones that exist independently of humans. The sciences are discovered, not invented.

I also see technology as a creative process involving human ingenuity. Emphasis upon making, creativity, and ingenuity can be traced back to teks, an Indo-European root of the word “technology.” Teks meant to fabricate or to weave. In the Greek, tektön referred to a carpenter or builder and tekhnë to an art, craft, or skill. All of these early meanings suggest a process of making, even of creation. In the Middle Ages, the mechanical arts of weaving, weapon making, navigation, agriculture, and hunting involved building, fabrication, and other productive activities, not simply artifacts.

Landscape architect Anne Whiston Spirn’s definition of landscape in The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design (1984) suggests a way of thinking about technology. For her, landscape connects people and a place, and it involves the shaping of the land by people and people by the land. The land is not simply scenery; it is both the natural, or the given, and the human-built. It includes buildings as well as trees, rocks, mountains, lakes, and seas. I see technology as a means to shape the landscape.

As noted, “technology” was infrequently used until the late twentieth century. When a group of about twenty American historians and social scientists formed the Society for the History of Technology in 1958, they debated whether the society should be known by the familiar word “engineering” or the unfamiliar one “technology.” They decided upon the latter, believing “technology,” though the less used and less well-defined term, to be a more inclusive term than “engineering,” an activity that it subsumes.

So historians of technology today are applying the word to activities and things in the past not then known as technology, but that are similar to activities and things in the present that are called technology. For example, machines in the nineteenth century and mills in the medieval period are called technology today, but they were not so designated by contemporaries, who called them simply machines and mills.

In 1959 the Society for the History of Technology began publication of a quarterly journal entitled Technology and Culture. The bewildering variety of things and systems referred to as technology in the journal’s first two decades reveals technology’s complex character. Rockets, steam and internal combustion engines, machine tools, textiles, computers, telegraphs, telephones, paper, telemetry, photography, radio, metals, weapons, chemicals, land transport, production systems, agricultural machines, water transport, tools, and instruments all appear as technology in the journal’s pages. Yet the various kinds of technology noted in Technology and Culture have a common denominator—most can be associated with the creative activities, individual and collective, of craftsmen, mechanics, inventors, engineers, designers, and scientists. By limiting technology to their creative activities, I can avoid an unbounded definition that would include, say, the technology of cooking and coaching, as widespread as they may be.

Having taught the history of technology for decades and having faced the difficulties of defining it in detail, I have resorted to an overarching definition, one that covers how I use the term in the following chapters. I see technology as craftsmen, mechanics, inventors, engineers, designers, and scientists using tools, machines, and knowledge to create and control a human-built world consisting of artifacts and systems associated mostly with the traditional fields of civil, mechanical, electrical, mining, materials, and chemical engineering. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, however, the artifacts and systems also become associated with newer fields of engineering, such as aeronautical, industrial, computer, and environmental engineering, as well as bioengineering.

Besides seeing technology associated with engineering, I also consider it being used as a tool and as a source of symbols by many architects and artists. This view of technology allows me to stress the aesthetic dimensions of technology, which unfortunately have been neglected in the training of engineers, scientists, and others engaged with technology.

My background helps explain why I have chosen a definition emphasizing creativity and control. Before earning a Ph.D. in modern European history, I received a degree in mechanical and electrical engineering. In the 1950s, I found engineering and related technology at their best to be creative endeavors. Not uncritical of their social effects, I still considered them potentially a positive force and expressed a tempered enthusiasm for them and their practitioners.

Since then, I have learned about the Janus face of technology from counterculture critics, environmentalists, and environmental historians. Yet the traces of my enthusiasm still come through in my publications, especially this one. Hence my defining technology as a creative activity, hence my willingness to sympathetically portray those who have seen technology as evidence of a divine spark, and hence my interest in those who consider the machine a means to make a better world. Yet this sympathetic view is qualified by what I have learned from critics of technology.

Overarching Theme: Creativity

Despite the varied approaches to technology taken by the authors, artists, and architects considered in this book, I find several overarching and related themes emerging as my account moves from the past toward the present. Most of my sources see technology, as I do, offering creative means to a variety of ends. They explore the various uses of technology. They also understand it to be especially important as means to create and to control a human-built world, the extent of which is steadily increasing. As a result, my sources have given me and should give my readers a far greater appreciation of our responsibilities for the use of technology and for the characteristics of the human-built world it creates.

Creativity is usually associated with the fine arts and architecture, yet technology throughout history has enabled humans to exercise godlike creative powers. For the Greeks, Prometheus symbolized creativity in stealing fire from the gods, not with paint and canvas. Conventionally seen as a gifted artist, Leonardo da Vinci presented himself to the world as an architect-engineer who filled his notebooks with inventions and engineering projects, including canals, automated textile machines, and machine tools. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in his epic poem Faust had the protagonist ultimately finding earthly fulfillment in the creation, by the drainage of wetlands, of new land upon which humans will thrive.

Today in a secular age dedicated to a consumer culture, we do not see technology in the grand perspective suggested by Leonardo and Goethe. We are content to let inventors and entrepreneurs, energized by market forces, lay claim to the laurels of creativity. During the past century, American inventors became heroic figures symbolizing the country’s aptitude for innovation. Thomas Edison remains the foremost independent inventor-entrepreneur remembered for his electric light, phonograph, telegraph, and numerous other inventions. He was the proverbial small-town, plainspoken, self-made American whose untutored genius brought him fame and wealth. How unlike the highly complex Leonardo, who was both artist and engineer.

We should not be surprised that a century later Americans eager to recapture and refresh their image as a nation of inventors relish stories about a new wave of youthful inventor-entrepreneurs preparing business plans to finance Silicon Valley start-up companies that are intended to stimulate a computer revolution. Goethe’s Faust would hardly have asked the moment of creation to linger, if the result was simply one more consumer good.

Along with inventors, engineers are also seen today as the creators of the human-built world. During the last century, Americans and Germans pictured engineers as robust, commonsensical, practical, self-made, rather dull men. With the late-nineteenth-century rise of engineering schools, an engineering education became the means for young men of humble origins to move up into the ranks of industrial managers and preside over a market-driven industrial scene. Only within the past few decades have women in substantial numbers been encouraged to enroll in engineering schools and to enter the profession. Perhaps they will introduce more complexity into a profession inclined toward reductionism.

Overarching Theme: Human-Built World

According to the myth of creation found in the book of Genesis, humans have been engaged in creating a living and working place, a human-built world, ever since their ouster from the Garden of Eden. There, Eve and Adam did not have to provide food, clothing, or shelter for themselves. Subsequently humans used technology to transform an uncultivated physical environment into a cultivated and human-built one with all of its artifacts and systems.

The transformation has been especially rapid and obvious during industrial revolutions beginning in England in the eighteenth century, extending to the United States and Germany in the nineteenth, and into Japan and other regions of the developing world in the twentieth. In order to define the concept of the human-built, I could focus upon history in countless times and places, but a brief survey of the American experience should suffice. By 1900 even Europeans acknowledged that the United States had become technology’s nation.

In the traditional account, Americans transformed an uncultivated wilderness into a living and work place—the human-built world. In recent years, however, historians have revealed that at least a million Native Americans inhabited the so-called wilderness of the seventeenth century and they had changed the landscape by controlled burning of grasslands, clearing of forests, and the planting of crops.

There are no better defining examples of the human-built than the industrial metropolises that mushroomed in the United States during the late nineteenth century. Young men and women who knew exhausting labor of the farms flocked into expanding industrial cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Cleveland, and Chicago with their diversions and promise of blue- and white-collar work.

Living in a human-built urban world shaped American character, as my sources will testify. Unlike Frederick Jackson Turner, an eminent historian, who in his essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” (1893) wrote persuasively of the influence of the natural frontier on American character, I am more interested in the ways in which the human-built environment has shaped character. Early in the nineteenth century, Turner asked his readers to stand at Kentucky’s Cumberland Gap and watch successive waves of Indians, fur traders, hunters, cattle raisers, and pioneer farmers flowing westward. He believed that frontier experiences brought them and later Americans to favor political democracy, cross-pollination of ethnic groups, inquisitiveness, materialism, and individualism.

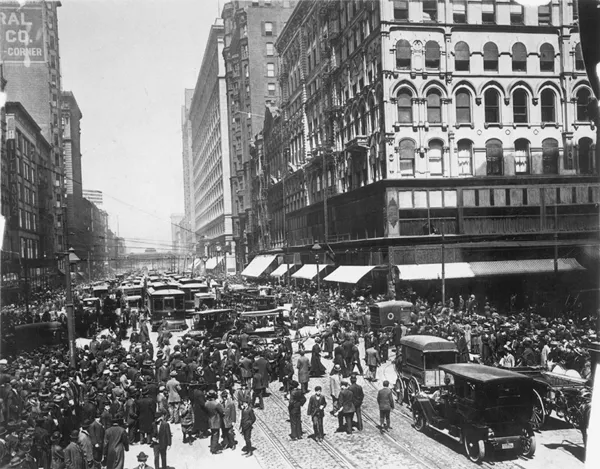

Instead of natural frontier images, I seek, through my sources, images capturing the essence of the human-built world. It can be observed on the streets of industrial Chicago in 1910 populated by skilled blue-collar workmen, eager young inventors, aspiring white-collared managers, and upwardly mobile, clean-shaven farm boys become mechanical engineers. There were also young women born and bred in small towns finding employment as clerks in the newly established department stores, as stenographers in places of business, and as laborers in manufacturing shops. The tumultuous pace and the callous demands of a commercial culture overwhelmed some young men and women who drifted into the urban slums or into prostitution or petty crime.

Many of them flourished, however, as their country—once despised by industrial Britain as rural and uncouth—became the world’s preeminent industrial and technological power. A construction site for centuries, America spawned a nation of builders. The business of America was building. The spirit of the people was not only free enterprise, but also demiurge—the spirit of the Greek god who created the material world.

1. Not a tree or a blade of grass in human-built Chicago, ca. 1910. Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

Seeing a human-built world around them, engineers, scientists, and managers believed that they had the creative technological power to make a world according to their own blueprints. They considered the natural world as expendable and exploitable or simply as scenery. Railroads, highways, telegraphs, and telephones allowed transportation and communication systems to reach the remote hinterland. Electric power energized factories far from the rail networks serving industry dependent upon coal. Artificial fertilizers and agricultural machinery increased the yield of lands once exhausted. Chemists transformed matter and provided abundance where nature had denied resources, even though the side effects were hidden for decades. The creative spirit, the desire to create a human-built world, was reaching its apogee.

My sources develop not only upon the overarching themes of creativity and the human-built, but also subthemes dealing with the varied ends that technology can serve. I develop these subthemes in individual chapters that are arranged chronologically. Before discussing the subtheme explored in a chapter, I provide context by surveying technological developments taking place during the periods in which the subtheme most obviously emerged.

Second Creation

Chapter 2, for instance, focuses upon...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Series Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Introduction: Complex Technology

- 2. Technology and the Second Creation

- 3. Technology as Machine

- 4. Technology as Systems, Controls, and Information

- 5. Technology and Culture

- 6. Creating an Ecotechnological Environment

- Notes

- Bibliographic Essay

- Index