![]()

PART 1

THE NATURE OF SEGREGATION

A fundamental tenet of the environmental justice movement, as Dana Alston first gave it voice in 1991, is the notion that the environment should be understood to encompass not only places dominated by Nature with a capital N, but also the everyday places “where we live, where we work and where we play.” Historically, this definition has mattered for people of color because deeply rooted practices of racial segregation have shaped the environments they occupy in fundamental ways. Throughout the period after World War II, in every region of the country and across the spectrum from rural to urban, formal and informal practices of segregation have systematically shunted people of color into the least desirable places and barred them from the most desirable ones. In postwar America, separate environments have seldom been created equal.

![]()

“WHERE WE LIVE”

This section focuses on the domestic spaces and neighborhoods where people of color lived starting in the era of segregation and moving into the civil rights era. The first four documents come from a stunning collection of images held by the Library of Congress, known as the Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information photographs (FSA/OWI). This New Deal project, which employed documentary photographers to chronicle American life, produced some 175,000 photographs in the years immediately before and during World War II, between 1935 and 1944. The first, from November 1938, is a photograph of the home of a family of African American farmers in Louisiana. The second, taken in 1941, shows an African American slum district in Norfolk, Virginia, in which the backed-up sewer is only the most obvious indication of neglect. The third, from 1935, shows the kitchen of a slum rental apartment’s kitchen, with chipped plaster and peeling paint, located near the US Capitol Dome in Washington, DC. The fourth, taken in California’s Imperial Valley in 1937, shows a migratory Mexican field-worker’s home on the edge of a field. When you encounter photographs in this book, it is reasonable to wonder how representative they are. What are the strengths and limits of this kind of evidence? How should we interpret what we see? It is also reasonable to wonder how evidence from the years immediately preceding World War II compares to conditions after the war. What might have changed, and how would we know?

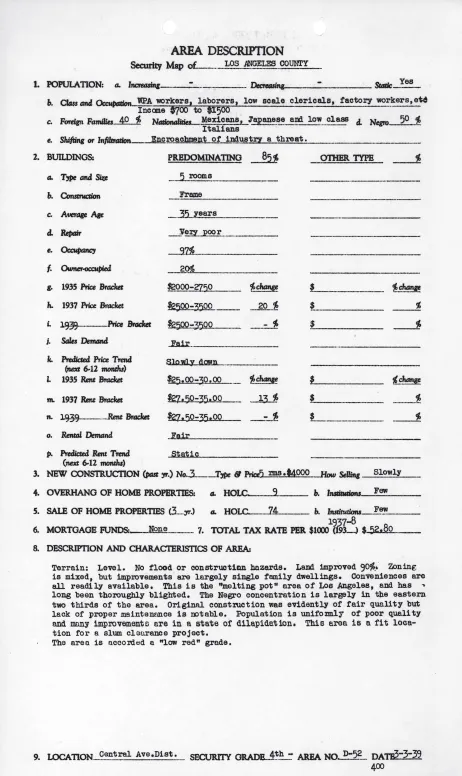

The next five documents reflect some of the racially discriminatory legal and financial practices that affected the type and location of housing available to people of color. The first document, a data sheet from a Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) appraisal of a Los Angeles neighborhood in 1939, illustrates the practice of redlining. The practice derived its name from the color-coded rating system devised by the HOLC, which had been created in 1933 as part of the New Deal’s efforts to save the struggling housing industry. By assigning different colors to different neighborhoods, HOLC maps allowed banks (and the Federal Housing Administration) to assess the risks of issuing loans based on a home’s location. Green and blue neighborhoods were “best” and “still desirable,” respectively. Yellow areas were “definitely declining.” Red areas, on the other hand, signaled neighborhoods characterized by older housing, physical deterioration, and poverty, and were deemed too risky for investment. According to the HOLC’s underwriting criteria, neighborhoods could earn a red designation simply for having African American residents.

Two obvious effects of this system were to bar most African Americans from taking advantage of postwar federal homeownership programs that fostered upward mobility and to drain postwar African American neighborhoods of capital and investment. But the HOLC’s emphasis on maintaining racially “homogenous” populations and on the “prevention of infiltration” by “inharmonious racial groups” also created enormous financial incentives for white homeowners to protect their home values by maintaining rigid segregation. The next two documents depict the perverse extremes that such a policy could inspire: in this case, a half-mile-long concrete wall, erected by a developer in 1941 to separate a new (white) development from an adjacent (black) neighborhood in Detroit. Without the wall, the FHA did not approve the project. With it, it did.

The next document illustrates a very different but also effective technique that maintained segregated housing. It collects various examples of “restrictive covenants,” or clauses written into property deeds that legally restricted members of named minority groups from buying, renting, or occupying certain properties, even when owners were otherwise willing. Used widely across the country between the First World War and 1948, when the Supreme Court declared them unenforceable, restrictive covenants like these were a key legal mechanism for maintaining racially segregated housing and confining people of color to segregated ghettos.

In the years after World War II, in the context of an acute housing shortage in which vast quantities of new housing were needed, the question of whether or not discriminatory practices like redlining and racially restrictive covenants should be allowed to continue sparked public debate. Some, like Charles Abrams, a leading housing reformer and public intellectual, cast the question in stark moral terms. Would federal policy aim to “[recast] our communities in a democratic mold,” he asked in 1947, or would it cave in to “pressures to perpetuate segregation”?1

Pressure to maintain segregation came in different forms, as the next several documents show. One of the most obvious forms of pressure came in overt expressions of hatred and violence. The first document, a famous photograph taken by Arthur Siegel in February 1942, is part of a series documenting a riot at the new Sojourner Truth housing project in Detroit, which broke out when white neighbors tried to prevent its first African American tenants from moving in. The next document, an excerpt from a 1954 Saturday Evening Post feature article on William Levitt, the president of the country’s largest suburban developer, Levitt and Sons, explains his family’s choice not to “sell their houses to Negroes.” This is followed by a Saturday Evening Post exposé, published in 1962, that explains the lucrative practice known as “block busting,” by which speculators capitalized on the volatile cocktail of racial tensions, housing shortages, financial incentives, and prevailing real estate practices to “drive the whites from a block whether or not they want to go, then move in Negroes.” The author uses crude language that displays obvious individual bigotry, but he also makes clear that his personal feelings about race are a small part of a much bigger pattern. More important than his individual attitudes is the fact that his actions—and those of other blockbusters—enjoy the full sanction of local politicians, police, realty organizations, and the press.

The final four documents in this section illustrate the importance of housing-related issues as a key item on the civil rights movement’s agenda. The first is a photo of the Civil Rights March on Washington, DC, on August 28, 1963, which is best known as the venue for Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. It shows leaders Roy Wilkins (NAACP), A. Philip Randolph (AFL-CIO), and Walter Reuther (UAW) holding hands in the foreground, with marchers carrying signs behind them that proclaim various priorities. The second photo shows three picketers outside the Seattle offices of the National Association of Real Estate Boards protesting the discriminatory practices of realtors. The third document, an excerpt from the Fair Housing Act of 1968, marks one of the civil rights movement’s signal legal victories, the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which President Lyndon Johnson signed into law in the midst of nationwide riots in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. The fourth document, excerpted from a US Commission on Civil Rights pamphlet, “Understanding Fair Housing” (1973), explains the significance of efforts to secure equal housing, while cautioning that even sweeping legal victories were unlikely to eliminate segregation.

NOTE

1 Charles Abrams, “Race Bias in Housing: The Great Hypocrisy,” Nation, July 19, 1947, 67–69.

RUSSELL LEE

SHACK OF NEGRO FAMILY FARMERS LIVING NEAR JARREAU, LOUISIANA, 1938

Russell Lee, Shack of Negro Family Farmers Living near Jarreau, Louisiana, Nov. 1938, Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF33- 011891-M4 [P&P], www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/fsa.8a24792.

JOHN VACHON

BACKED UP SEWER IN NEGRO SLUM DISTRICT, NORFOLK, VIRGINIA, 1941

John Vachon, Backed Up Sewer in Negro Slum District, Norfolk, Virginia, March 1941, Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USF34-062567-D, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa2000043236/PP.

CARL MYDANS

KITCHEN OF NEGRO DWELLING IN SLUM AREA NEAR HOUSE OFFICE BUILDING, WASHINGTON, D.C., 1935

Carl Mydans, Kitchen of Negro Dwelling in Slum Area near House Office Building, Washington, D.C., Sept. 1935, Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF33- 000115-M1, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa1997000120/PP.

DOROTHEA LANGE

MIGRATORY MEXICAN FIELD WORKER’S HOME ON THE EDGE OF A FROZEN PEA FIELD, IMPERIAL VALLEY, CALIFORNIA, 1937

Dorothea Lange, Migratory Mexican Field Worker’s Home on the Edge of a Frozen Pea Field, Imperial Valley, California, March 1937, Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF34- 016425-C, www.loc.gov/item/fsa2000001016/PP.

HOME OWNERS LOAN CORPORATION

LOS ANGELES DATA SHEET D52, 1939

Home Owners Loan Corporation data sheet D52, March 1939, Los Angeles, from Mapping Inequality, dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=11/34.0051/-118.3701&opacity=0.86&city=los-angeles-ca&sort=16&area=D52.

JOHN VACHON

NEGRO CHILDREN STANDING IN FRONT OF HALF MILE CONCRETE WALL, DETROIT, MICHIGAN, 1941

John Vachon, Negro Children Standing in Front of Half Mile Concrete Wall, Detroit, Michigan. This Wall Was Built in August 1941, to Separate the Negro Section from a White Housing Development Going Up on the Other Side, Aug. 1941, Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF34-063679-D and -063680 [P&P], www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/fsa.8c20121and/fsa.8c20122.

EXAMPLES OF RACIALLY RESTRICTIVE REAL ESTATE COVENANTS

No part of the land hereby conveyed shall ever be used or occupied or sold, demised, transferred, conveyed unto, or in trust for, leased, rented, or given to Negroes, or any person of the Semitic race or origin, which racial designation shall be deemed to include Armenians, Jews, Hebrews, Persians, Egyptians.1

This property shall not be used or occupied by any person or persons except those of the Caucasian race.2

Hereafter no part of said property or any portion thereof shall be … occupied by any person not of the Caucasian race, it being intended hereby to restrict the use of said property … against the occupancy as owners or tenants of any portion of said property for resident or other purpose by people of the Negro or Mongolian race.3

No person of any race other than (race to be inserted) shall use or occupy any building or any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race domiciled with an owner or tenant.4

That said premises shall not at any time hereafter be sold, leased or transferred to any colored person or persons or to any person or persons of the Ethiopian or Semetic Race or to any...