- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In How Will Capitalism End?, the acclaimed analyst of contempo?rary politics and economics Wolfgang Streeck argues that the world is on the cusp of enormous change. The marriage between democracy and capitalism, ill-suited partners brought together in the shadow of the Second World War, is unravelling. The regulatory institutions that once restrained the financial sector's excesses have collapsed, and there is no political agency capable of rolling back the liberalization of the markets.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How Will Capitalism End? by Wolfgang Streeck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Volkswirtschaftslehre & Volkswirtschaft. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

How Will Capitalism End?

There is a widespread sense today that capitalism is in critical condition, more so than at any time since the end of the Second World War.1 Looking back, the crash of 2008 was only the latest in a long sequence of political and economic disorders that began with the end of post-war prosperity in the mid-1970s. Successive crises have proved to be ever more severe, spreading more widely and rapidly through an increasingly interconnected global economy. Global inflation in the 1970s was followed by rising public debt in the 1980s, and fiscal consolidation in the 1990s was accompanied by a steep increase in private-sector indebtedness.2 For four decades now, disequilibrium has more or less been the normal condition of the ‘advanced’ industrial world, at both the national and the global levels. In fact, with time, the crises of post-war OECD capitalism have become so pervasive that they have increasingly been perceived as more than just economic in nature, resulting in a rediscovery of the older notion of a capitalist society – of capitalism as a social order and way of life, vitally dependent on the uninterrupted progress of private capital accumulation.

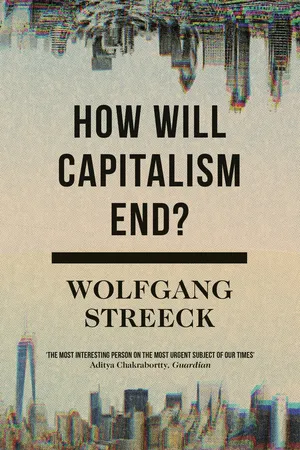

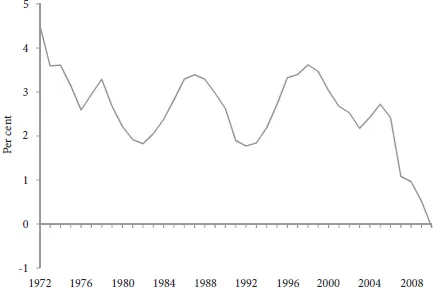

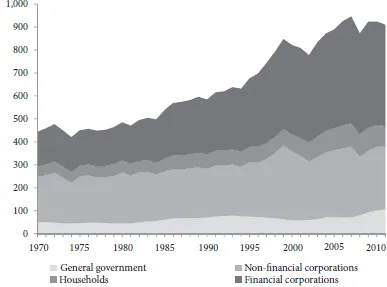

Crisis symptoms are many, but prominent among them are three long-term trends in the trajectories of rich, highly industrialized – or better, increasingly deindustrialized – capitalist countries. The first is a persistent decline in the rate of economic growth, recently aggravated by the events of 2008 (Figure 1.1). The second, associated with the first, is an equally persistent rise in overall indebtedness in leading capitalist states, where governments, private households and non-financial as well as financial firms have, over forty years, continued to pile up financial obligations (for the U.S., see Figure 1.2). Third, economic inequality, of both income and wealth, has been on the ascent for several decades now (Figure 1.3), alongside rising debt and declining growth.

Figure 1.1: Annual average growth rates of twenty OECD countries, 1972–2010*

*Five-year moving average

Source: OECD Economic Outlook.

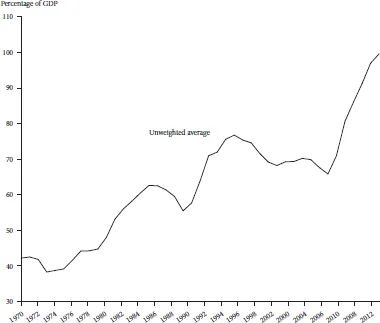

Figure 1.2: Liabilities as a percentage of U.S. GDP by sector, 1970–2011

Source: OECD National Accounts.

Figure 1.3: Increase in GINI coefficient, OECD average

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database.

Steady growth, sound money and a modicum of social equity, spreading some of the benefits of capitalism to those without capital, were long considered prerequisites for a capitalist political economy to command the legitimacy it needs. What must be most alarming from this perspective is that the three critical trends I have mentioned may be mutually reinforcing. There is mounting evidence that increasing inequality may be one of the causes of declining growth, as inequality both impedes improvements in productivity and weakens demand. Low growth, in turn, reinforces inequality by intensifying distributional conflict, making concessions to the poor more costly for the rich, and making the rich insist more than before on strict observance of the ‘Matthew principle’ governing free markets: ‘For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken even that which he hath.’3 Furthermore, rising debt, while failing to halt the decline of economic growth, compounds inequality through the structural changes associated with financialization – which in turn aimed to compensate wage earners and consumers for the growing income inequality caused by stagnant wages and cutbacks in public services.

Can what appears to be a vicious circle of harmful trends continue forever? Are there counterforces that might break it – and what will happen if they fail to materialize, as they have for almost four decades now? Historians inform us that crises are nothing new under capitalism, and may in fact be required for its longer-term health. But what they are talking about are cyclical movements or random shocks, after which capitalist economies can move into a new equilibrium, at least temporarily. What we are seeing today, however, appears in retrospect to be a continuous process of gradual decay, protracted but apparently all the more inexorable. Recovery from the occasional Reinigungskrise is one thing; interrupting a concatenation of intertwined, long-term trends quite another. Assuming that ever lower growth, ever higher inequality and ever rising debt are not indefinitely sustainable, and may together issue in a crisis that is systemic in nature – one whose character we have difficulty imagining – can we see signs of an impending reversal?

ANOTHER STOPGAP

Here the news is not good. Six years have passed since 2008, the culmination so far of the post-war crisis sequence. While memory of the abyss was still fresh, demands and blueprints for ‘reform’ to protect the world from a replay abounded. International conferences and summit meetings of all kinds followed hot on each other’s heels, but half a decade later hardly anything has come from them. In the meantime, the financial industry, where the disaster originated, has staged a full recovery: profits, dividends, salaries and bonuses are back where they were, while re-regulation became mired in international negotiations and domestic lobbying. Governments, first and foremost that of the United States, have remained firmly in the grip of the money-making industries. These, in turn, are being generously provided with cheap cash, created out of thin air on their behalf by their friends in the central banks – prominent among them the former Goldman Sachs man Mario Draghi at the helm of the ECB – money which they then sit on or invest in government debt. Growth remains anaemic, as do labour markets; unprecedented liquidity has failed to jump-start the economy; and inequality is reaching ever more astonishing heights, as what little growth there is has been appropriated by the top 1 per cent of income earners – the lion’s share by a small fraction of them.4

There would seem to be little reason indeed to be optimistic. For some time now, OECD capitalism has been kept going by liberal injections of fiat money, under a policy of monetary expansion whose architects know better than anyone else that it cannot continue forever. In fact, several attempts were made in 2013 to kick the habit, in Japan as well as in the U.S., but when stock prices plunged in response, ‘tapering’, as it came to be called, was postponed for the time being. In mid-June, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in Basel – the mother of all central banks – declared that ‘quantitative easing’ must come to an end. In its Annual Report, the Bank pointed out that central banks had, in reaction to the crisis and the slow recovery, expanded their balance sheets, ‘which are now collectively at roughly three times their pre-crisis level – and rising’.5 While this had been necessary to ‘prevent financial collapse’, now the goal had to be ‘to return still-sluggish economies to strong and sustainable growth’. This, however, was beyond the capacities of central banks, which:

cannot enact the structural economic and financial reforms needed to return economies to the real growth paths authorities and their publics both want and expect. What central-bank accommodation has done during the recovery is to borrow time … But the time has not been well used, as continued low interest rates and unconventional policies have made it easy for the private sector to postpone deleveraging, easy for the government to finance deficits, and easy for the authorities to delay needed reforms in the real economy and in the financial system. After all, cheap money makes it easier to borrow than to save, easier to spend than to tax, easier to remain the same than to change.

Apparently, this view was shared even by the Federal Reserve under Bernanke. By the late summer of 2013, it seemed once more to be signalling that the time of easy money was coming to an end. In September, however, the expected return to higher interest rates was again put off. The reason given was that ‘the economy’ looked less ‘strong’ than was hoped. Global stock prices immediately went up. The real reason why a return to more conventional monetary policies is so difficult, of course, is one that an international institution like BIS is freer to spell out than a – for the time being – more politically exposed national central bank. This is that as things stand, the only alternative to sustaining capitalism by means of an unlimited money supply is trying to revive it through neoliberal economic reform, as neatly encapsulated in the second subtitle of the BIS’s 2012–13 Annual Report: ‘Enhancing Flexibility: A Key to Growth’. In other words, bitter medicine for the many, combined with higher incentives for the few.6

A PROBLEM WITH DEMOCRACY

It is here that discussion of the crisis and the future of modern capitalism must turn to democratic politics. Capitalism and democracy had long been considered adversaries, until the post-war settlement seemed to have accomplished their reconciliation. Well into the twentieth century, owners of capital had been afraid of democratic majorities abolishing private property, while workers and their organizations expected capitalists to finance a return to authoritarian rule in defence of their privileges. Only in the Cold War world did capitalism and democracy seem to become aligned with one another, as economic progress made it possible for working-class majorities to accept a free-market, private-property regime, in turn making it appear that democratic freedom was inseparable from, and indeed depended on, the freedom of markets and profit-making. Today, however, doubts about the compatibility of a capitalist economy with a democratic polity have powerfully returned. Among ordinary people, there is now a pervasive sense that politics can no longer make a difference in their lives, as reflected in common perceptions of deadlock, incompetence and corruption among what seems an increasingly self-contained and self-serving political class, united in their claim that ‘there is no alternative’ to them and their policies. One result is declining electoral turnout combined with high voter volatility, producing ever greater electoral fragmentation, due to the rise of ‘populist’ protest parties, and pervasive government instability.7

The legitimacy of post-war democracy was based on the premise that states had a capacity to intervene in markets and correct their outcomes in the interest of citizens. Decades of rising inequality have cast doubt on this, as has the impotence of governments before, during and after the crisis of 2008. In response to their growing irrelevance in a global market economy, governments and political parties in OECD democracies more or less happily looked on as the ‘democratic class struggle’ turned into post-democratic politainment.8 In the meantime, the transformation of the capitalist political economy from post-war Keynesianism to neoliberal Hayekianism progressed smoothly: from a political formula for economic growth through redistribution from the top to the bottom, to one expecting growth through redistribution from the bottom to the top. Egalitarian democracy, regarded under Keynesianism as economically productive, is considered a drag on efficiency under contemporary Hayekianism, where growth is to derive from insulation of markets – and of the cumulative advantage they entail – against redistributive political distortions.

A central topic of current anti-democratic rhetoric is the fiscal crisis of the contemporary state, as reflected in the astonishing increase in public debt since the 1970s (Figure 1.4). Growing public indebtedness is put down to electoral majorities living beyond their means by exploiting their societies’ ‘common pool’, and to opportunistic politicians buying the support of myopic voters with money they do not have.9 However, that the fiscal crisis was unlikely to have been caused by an excess of redistributive democracy can be seen from the fact that the build-up of government debt coincided with a decline in electoral participation, especially at the lower end of the income scale, and marched in lockstep with shrinking unionization, the disappearance of strikes, welfare-state cutbacks and exploding income inequality. What the deterioration of public finances was related to was declining overall levels of taxation (Figure 1.5) and the increasingly regressive character of tax systems, as a result of ‘reforms’ of top income and corporate tax rates (Figure 1.6). Moreover, by replacing tax revenue with debt, governments contributed further to inequality, in that they offered secure investment opportunities to those whose money they would or could no longer confiscate and had to borrow instead. Unlike taxpayers, buyers of government bonds continue to own what they pay to the state, and in fact collect interest on it, typically paid out of ever less progressive taxation; they can also pass it on to their children. Moreover, rising public debt can be and is being utilized politically to argue for cutbacks in state spending and for privatization of public services, further constraining redistributive democratic intervention in the capitalist economy.

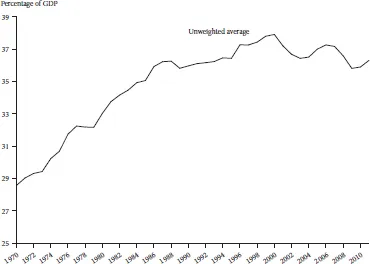

Figure 1.4: Government debt as a percentage of GDP, 1970–2013

Countries included: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, U.K., U.S. Source: OECD Economic Outlook No. 95.

Figure 1.5: Total tax revenue as a percentage of GDP, 1970–2011

Countries included: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, U.K., U.S.

Source: OECD Revenue Statistics.

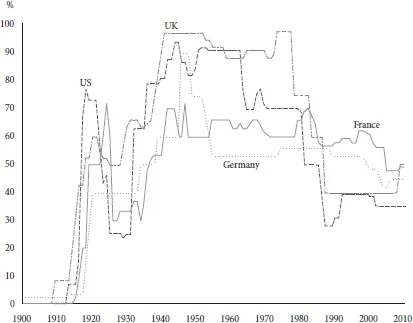

Figure 1.6: Top marginal income tax rates, 1900–2011

Source: Facundo Alvaredo, Anthony Atkinson, Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, ‘The Top 1 per cent in International and Historical Perspective’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 27, no. 3, 2013.

Institutional protection of the market economy from democratic interference has advanced greatly in recent decades. Trade unions are on the decline everywhere and have in many countries been all but rooted out, especially in the U.S. Economic policy has widely been turned over to independent – i.e., democratically unaccountable – central banks concerned above all with the health and goodwill of financial markets.10 In Europe, national economic policies, including wage-setting and budget-making, are increasingly governed by supranational agencies like the European Commission and the European Central Bank that lie beyond the reach of popular democracy. This effectively de-democratizes European capitalism – without, of course, de-politicizing it.

Still, doubts remain among the profit-dependent classes as to whether democracy will, even in its emasculated contemporary version, allow for the neoliberal ‘structural reforms’ necessary for their regime to recover. Like ordinary citizens, although for the opposite reasons, elites are losing faith in democratic government and its suitability for reshaping societies in line with market imperatives. Public Choice’s disparaging view of democratic politics as a corruption of market justice, in the service of opportunistic politicians and their clientele, has become common sense among elite publics – as has the belief that market capitalism cleansed of democratic politics will not only be more efficient but also virtuous and responsible.11 Countries like China are complimented for their authoritarian political systems being so much better equipped than majoritarian democracy, with its egalitarian bent, to deal with what are claimed to be the challenges of ‘globalization’ – a rhetoric that is beginning conspicuously to resemble the celebration by capitalist elites during the interwar years of German and Italian Fascism (and even Stalinist Communism) for their apparently superior economic governance.12

For the time being, the neoliberal mainstream’s ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- A Note on the Text

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: How Will Capitalism End?

- Chapter 2: The Crises of Democratic Capitalism

- Chapter 3: Citizens as Customers: Considerations on the New Politics of Consumption

- Chapter 4: The Rise of the European Consolidation State

- Chapter 5: Markets and Peoples: Democratic Capitalism and European Integration

- Chapter 6: Heller, Schmitt and the Euro

- Chapter 7: Why the Euro Divides Europe

- Chapter 8: Comment on Wolfgang Merkel, ‘Is Capitalism Compatible with Democracy?’

- Chapter 9: How to Study Contemporary Capitalism?

- Chapter 10: On Fred Block, ‘Varieties of What? Should We Still Be Using the Concept of Capitalism?’

- Chapter 11: The Public Mission of Sociology

- Notes

- Index