- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The financial and economic crisis that began in 2008 still has the world on tenterhooks. The gravity of the situation is matched by a general paucity of understanding about what is happening and how it started.

In this book, based on his 2012 Adorno Lectures given in Frankfurt, Wolfgang Streeck places the crisis in the context of the long neoliberal transformation of postwar capitalism that began in the 1970s. He analyses the subsequent tensions and conflicts involving states, governments, voters and capitalist interests, as expressed in inflation, public debt, and rising private indebtedness. Streeck traces the transformation of the tax state into a debt state, and from there into the consolidation state of today. At the centre of the analysis is the changing relationship between capitalism and democracy, in Europe and elsewhere, and the advancing immunization of the former against the latter.

In this new edition, Streeck has added a substantial postface on the reception of the book and the unfolding of the crisis in the Eurozone since 2014.

In this book, based on his 2012 Adorno Lectures given in Frankfurt, Wolfgang Streeck places the crisis in the context of the long neoliberal transformation of postwar capitalism that began in the 1970s. He analyses the subsequent tensions and conflicts involving states, governments, voters and capitalist interests, as expressed in inflation, public debt, and rising private indebtedness. Streeck traces the transformation of the tax state into a debt state, and from there into the consolidation state of today. At the centre of the analysis is the changing relationship between capitalism and democracy, in Europe and elsewhere, and the advancing immunization of the former against the latter.

In this new edition, Streeck has added a substantial postface on the reception of the book and the unfolding of the crisis in the Eurozone since 2014.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Buying Time by Wolfgang Streeck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

From Legitimation Crisis to Fiscal Crisis

There is much to suggest that the neo-Marxist crisis theories circulating in Frankfurt in the 1960s and 1970s were wrongly thought to have been refuted in subsequent decades. Perhaps the transformation and dissolution of a major social formation such as capitalism simply takes rather longer – too long for impatient theorists who would like to know in their lifetime whether they have been right to hold the theories they did. Social change also seems to involve time-consuming detours which theoretically should not occur, and which can therefore be explained, if at all, only post hoc and ad hoc. In any event, I would argue that the crisis weighing capitalism down at the beginning of the twenty-first century – a crisis of its economy as well as its politics – can be understood only as the climax of a development which began in the mid-1970s and which the crisis theories of that time were the first attempts to interpret.

In retrospect, it is no longer disputed that the 1970s marked a turning-point:1 they brought the end of postwar reconstruction; the incipient breakdown of the international monetary system, which had been nothing less than a political world order for postwar capitalism;2 and the return of crisis-like disturbances and interruptions of economic activity as steps in capitalist development. Frankfurt sociologists, inspired by Marxism in various ways, were better placed than others to gain intuitive access to the political and economic drama of the times. Yet their attempts to grasp the distortions of the time – from the strike waves of 19683 to the first so-called oil crisis – within the broader historical context of modern capitalist development were soon all but forgotten, and so too were the practical ambitions invariably associated with crisis theory as critical theory. Too many surprising things had happened. The theory of ‘late capitalism’4 had tried to redefine the tensions and fractures in the political economy of the time. But the subsequent development of these, including their apparent resolution, eluded its theoretical grasp. One problem seems to have been that it essentially took over the characterization of the ‘golden years’ of postwar capitalism as a period of joint technocratic management by governments and large corporations, based upon and suited for the maintenance of stable growth and the eventual elimination of systemic crisis tendencies. What appeared critical to them was not the technical governability of modern capitalism but its social and cultural legitimation. Underestimating capital as a political actor and a strategic social force, while at the same time overestimating the capacity of government policy to plan and to act, they thus replaced economic theory with theories of the state and democracy; the penalty they paid was to forgo a key part of Marx’s legacy.

The crisis theory of the period around 1968 was partly or totally unprepared for three main developments. The first was that capitalism soon began, with astonishing success, its reversal to ‘self-regulated markets’, in the course of the neoliberal quest to revive the dynamic of capitalist accumulation through all manner of deregulation, privatization and market expansion. Anyone who experienced this at close quarters in the 1980s and 1990s soon ran into difficulties with the concept of late capitalism.5 The same was true, second, of predictions of a legitimation and motivation crisis. Already the 1970s saw a high and fast-spreading cultural acceptance of market-adjusted and market-driven ways of life, as expressed in particular in the eager demand of women for ‘alienated’ wage-labour or in the growth of the consumer society beyond all expectations.6 And, third, the economic crises accompanying the shift from postwar to neoliberal capitalism (especially the high inflation of the 1970s and the public debt of the 1980s) remained quite marginal to legitimation crisis theory7 – unlike for the Durkheim-inspired explanations of inflation as an expression of anomie resulting from distributional conflict,8 or for an author like James O’Connor, who as early as the late 1960s, albeit in the categories of an orthodox Marxist worldview, had predicted a ‘fiscal crisis of the state’ and an ensuing revolutionary-socialist alliance of unionized public employees and their clientele in the discarded surplus population.9

I would like to propose a historical narrative of capitalist development since the 1970s that links what I consider the revolt of capital against the postwar mixed economy with the broad popularity of expanding labour and consumer goods markets after the end of the short 1970s, and with the sequence of economic crisis phenomena from then until today (which has come to a head in a triple crisis of banking, public finances and economic growth). My account sees the ‘unleashing’10 of global capitalism in the last third of the twentieth century as a successful resistance on the part of those who own and dispose of capital – the ‘profit-dependent’ class – against the multiple constraints that post-1945 capitalism had had to endure in order to become politically acceptable again under the conditions of system competition. I explain this success, and the wholly unexpected revitalization of the capitalist system as a market economy, by reference inter alia to government policies that bought time for the existing economic and social order. This they achieved by generating mass allegiance to the neoliberal social project dressed up as a consumption project, first through inflation of the money supply, then through an accumulation of public debt, and finally through lavish credit to private households – something the theory of late capitalism could never have imagined. It is true that, after a time, each of these strategies burned itself out, in ways familiar to neo-Marxist crisis theory, in that they began to undermine the functioning of the capitalist economy, which requires expectations of a ‘just return’ to be privileged over all others. Legitimation problems therefore arose time and again, though not among the masses but among capital, in the shape of accumulation crises, which in turn posed dangers for the legitimation of the system with its democratically empowered populations. As we shall see, these could be overcome only by continued economic liberalization and the immunization of policy against pressure from below, so as to win back the confidence of ‘the markets’ in the system.

With hindsight, the crisis history of late capitalism since the 1970s appears as an unfolding of the old fundamental tension between capitalism and democracy – a gradual process that broke up the forced marriage arranged between the two after the Second World War. In so far as the legitimation problems of democratic capitalism turned into accumulation problems, their solution called for a progressive emancipation of the capitalist economy from democratic intervention. The securing of a mass base for modern capitalism thus shifted from the sphere of politics to the market, understood as a mechanism for the production of greed and fear,11 in a context of increasing insulation of the economy from mass democracy. I shall describe this as the transformation of the Keynesian political-economic institutional system of postwar capitalism into a neo-Hayekian economic regime.

My conclusion will be that, unlike the 1970s, we may now really be near the end of the postwar political–economic formation – an end which, albeit in a different way, was foretold and even wished for in the crisis theories of ‘late capitalism’. What I feel sure about is that the clock is ticking for democracy as we have come to know it, as it is about to be sterilized as redistributive mass democracy and reduced to a combination of the rule of law and public entertainment. This splitting of democracy from capitalism through the splitting of the economy from democracy – a process of de-democratization of capitalism through the de-economization of democracy – has come a long way since the crisis of 2008, in Europe just as elsewhere.

It must remain an open question, however, whether the clock is also ticking for capitalism. Institutionalized expectations in a transformed democracy under neoliberalism to make do with the justice of the market are evidently by no means incompatible with capitalism. But, despite all the efforts at re-education, diffuse expectations of social justice still present in sections of the population may resist channelling into laissez-faire market democracy and even provide an impetus for anarchistic protest movements. Such a possibility was indeed repeatedly considered in the old crisis theories. It is not clear, though, that protests of that kind are a threat to the capitalist ‘two-thirds society’ looming on the horizon or to global ‘plutonomy’;12 various techniques for managing an abandoned underclass, developed and tested in the United States, appear thoroughly exportable also to Europe. More critical could be the question of whether, if monetary doping with its potentially dangerous side effects has to be abandoned at some point, other growth drugs will be available to keep capital accumulation under way in the rich countries of the world. On this we can only speculate – as I do in the concluding remarks of this book.

A NEW TYPE OF CRISIS

Capitalism in the rich democratic countries has for several years now been in the throes of a threefold crisis, with no end in sight: a banking crisis, a crisis of public finances, and a crisis of the ‘real economy’. No one foresaw this unprecedented coincidence – not in the 1970s, but also not in the 1990s. In Germany, because of special conditions13 that had arisen more or less by chance and seem rather exotic to the outside world, the crisis hardly registered with people for years, and there was a tendency to warn against ‘hysteria’. In most of the other rich democracies, however, including the United States, the crisis cut deep into the lives of whole generations and by 2012 was in the process of turning the conditions of social existence upside down.

1) The banking crisis stems from the fact that, in the financialized capitalism of the Western world, too many banks had extended too much credit, both public and private, and that an unexpectedly large part of this suddenly turned bad. Since no bank can be sure that the bank with which it does business will not collapse overnight, banks are no longer willing to lend to one another.14 There also is the possibility that customers may feel compelled at any moment to start a run on banks and withdraw their deposits for fear they may otherwise lose them. Furthermore, since regulatory authorities expect banks to increase their capital reserves in proportion to the sums owed them, so as to reduce their risk exposure, the banks must cut back on their lending. It would help if states took over the bad loans, gave unlimited deposit protection and recapitalized the banks. The sums required for such a rescue operation could well prove astronomical, however, and governments are already overburdened with debt. At the same time, it might be as expensive, or even more expensive, if individual banks collapsed and others were dragged down with them. Here too, though – and this is the core of the problem – no more than guesses are possible.

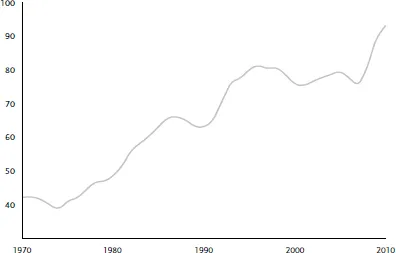

2) The fiscal crisis is the result of budget deficits and rising levels of government debt, which go back to the 1970s (Fig 1.1),15 as well as the borrowing required since 2008 to save both the finance industry (through the recapitalization of financial institutions and the acquisition of worthless debt securities) and the real economy (through fiscal stimuli). The increased risk of government insolvency in a number of countries is reflected in the higher costs of old and new debt. To regain the ‘confidence’ of ‘the markets’, governments impose harsh austerity measures on themselves and their citizens, with mutual supervision within the European Union, going as far as a general ban on new borrowing. That does not help to alleviate the banking crisis, or a fortiori the recession in the real economy. It is even debatable whether austerity reduces the debt burden, since it not only fails to promote growth but probably has a negative impact on it. And growth is at least as important as balanced budgets in lowering the national debt.

FIGURE 1.1

Public debt as percentage of national product: OECD average

Countries in unweighted average: Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, UK, USA

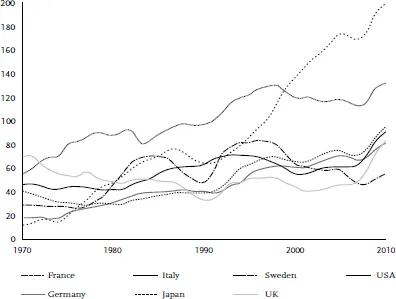

Public debt as percentage of national product: seven countries

Source: OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections

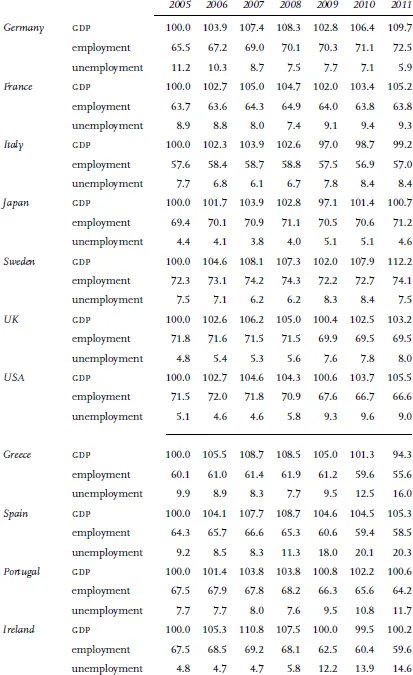

3) Finally, the crisis of the real economy manifest in high unemployment and stagnation (Fig. 1.2)16 partly stems from the fact that firms and consumers have difficulty in obtaining bank loans – because many of them are already deep in debt and the banks are risk-averse and short of capital – while governments have to curb their expenditure or, if it can no longer be avoided, raise taxes. Economic stagnation thus reinforces the fiscal crisis and, via resulting defaults, the crisis of the banking sector.

FIGURE 1.2. Effects of the 2008 crisis on the real economy

Sources: OECD (2012), ‘Public expenditure on active labour market policies’, Employment and Labour Markets: Key Tables from OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections, No. 9

It is clear that the three crises are closely interlinked: the first with the second through money; the first with the third through credit; and the second with the third through government spending and revenue. They continually reinforce one another, although their scale, urgency and interdependence vary from country to country. At the same time, multiple interactions occur between countries: failed banks in one country may drag down banks in others; a general rise in interest rates on...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Introduction: Crisis Theory: Then and Now

- Chapter One: From Legitimation Crisis to Fiscal Crisis

- Chapter Two: Neoliberal Reform: From Tax State to Debt State

- Chapter Three: The Politics of the Consolidation State: Neoliberalism in Europe

- Chapter Four: Looking Ahead

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index