- 472 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

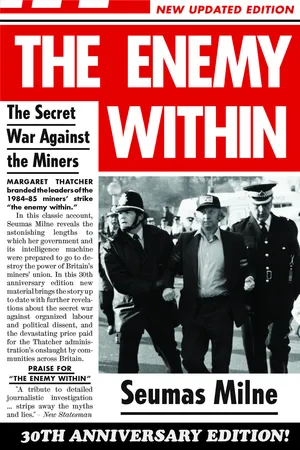

Margaret Thatcher branded the leaders of the 1984-85 miners' strike "the enemy within."

In this classic account, Seumas Milne reveals the astonishing lengths to which her government and its intelligence machine were prepared to go to destroy the power of Britain's miners' union. In this 30th anniversary edition new material brings the story up to date with further revelations about the secret war against organized labour and political dissent, and the devastating price paid for the Thatcher administration's onslaught by communities across Britain.

In this classic account, Seumas Milne reveals the astonishing lengths to which her government and its intelligence machine were prepared to go to destroy the power of Britain's miners' union. In this 30th anniversary edition new material brings the story up to date with further revelations about the secret war against organized labour and political dissent, and the devastating price paid for the Thatcher administration's onslaught by communities across Britain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Enemy Within by Seumas Milne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

OPERATION CYCLOPS

Our press, which you appear to regard as being free … is the most enslaved and the vilest thing. William Cobbett, 18301

The story that Robert Maxwell called the ‘Scoop of the Decade’ was launched with all the razzmatazz and hype of a major national event. The first signal of what would turn into an unrestrained media, legal and political barrage against the leaders of the most important industrial dispute since the 1920s came at 6 p.m. on Friday, 2 March 1990, almost exactly five years to the day after the end of the strike. One of the most popular television programmes in the country, the travel show Wish You Were Here, was to be ditched the following Monday, Central Television announced. In its place there would be a special edition of the investigative Cook Report. It was to be entitled: ‘The Miners’ Strike – Where Did the Money Go?’

The programme was primed to run as a joint exposé with Robert Maxwell’s Daily Mirror, and ITV’s last-minute scheduling switch followed intense haggling by Central’s director of broadcasting, Andy Allan, to secure a peak-viewing-time slot. It had been common knowledge for months in Fleet Street that the Mirror was sharpening its knives for a major hatchet-job on Arthur Scargill. Several disgruntled former NUM employees had been touting their wares around the media, and it was well known that Roger Windsor, the NUM’s former chief executive, and Jim Parker, Scargill’s ex-driver, had signed up with Maxwell. But Windsor was holed up in Southwest France and Parker was under the Mirror’s ‘protection’. Reporters working for Maxwell’s competitors chased around the country trying to inveigle the Mirror’s witnesses. At the NUM’s grandiose new headquarters opposite Sheffield City Hall, tension was close to breaking point. Scargill cancelled a planned trip to Australia while his inner circle attempted to second-guess the direction of the coming media offensive.

Slavering to beat its arch-rival to the kill, the Sun – with the Daily Star in hot pursuit – launched an immediate front-page ‘spoiler’ in response to Central’s rescheduling announcement. ‘Scargill Union in £1m Scandal’, the Murdoch tabloid screamed, correctly predicting that the Cook Report would claim that up to £1 million had been sent by Soviet miners to NUM strike funds, and at least £150,000 from Libya. ‘The programme is dynamite. The allegations are sensational’, the Sun enthused. The ‘harlot of Fleet Street’, as the Mirror liked to refer to the country’s biggest-selling daily, also latched on to police investigations into ‘Scargill’s former right hand man,’ Roger Windsor. An unfortunate Star reporter managed to buttonhole Windsor at his new home in Cognac, but was sent packing in short order. ‘The only guidance I will give you,’ Windsor told him, ‘is how to get back to the airport.’ A former NUM employee, the Sun predicted, would make ‘very serious allegations’ about the use of the Libyan money. But, for all its inventiveness, the Rottweiler of daily journalism was unable to establish exactly what these allegations might be.2

Nevertheless, the fear that the prize revelations his minions had been toiling over for the previous eight months, at a cost of hundreds of thousands of pounds, were being lost to his enemies sent the Mirror’s proprietor into a tailspin. His most recent acquisition as Daily Mirror editor, Roy Greenslade, was summoned and ordered to arrange for the Mirror Group’s Sunday title to run a ‘taster’ of the following week’s poison fare, trailed as the ‘full and shocking truth’. That would turn out to be a remorseless seven days of bewildering allegations against the NUM leadership in the daily paper most widely read by British miners and Labour-supporting trade unionists. In the week between 4 and 10 March 1990, the Sunday and Daily Mirror – each with a circulation of getting on for four million copies –would between them publish twenty-five pages of reports and commentary about Scargill and the ‘dishonour’ he had brought on the miners’ union.3

The taster chosen for the Sunday Mirror was a suitably titillating morsel about missing ‘Moscow Gold’. In December 1984, at Mikhail Gorbachev’s first meeting with Margaret Thatcher at Chequers, the paper revealed, the British Prime Minister had taken the future Soviet leader aside after lunch to express her ‘great displeasure’ about Soviet ‘meddling’ in the miners’ strike, then in its ninth month. ‘We believe that people in the Soviet Union … are helping to prolong the strike’, Thatcher told him. Gorbachev insisted that the strike was an internal British affair, and that as far as he was aware ‘no money has been transferred from the Soviet Union’. The Prime Minister ‘did not push the matter further’ and later that day declared: ‘This is a man we can do business with.’

But, the Sunday Mirror declared triumphantly, the NUM ‘did receive Soviet cash’ and the paper produced what it called ‘documentary proof’: a copy of a letter written in November 1984 by Peter Heathfield to the Soviet president, Konstantin Chernenko, and subsequently ‘removed’ from NUM files. Heathfield was quoted expressing gratitude for the solidarity of the Soviet trade unions, including ‘financial assistance to relieve the hardship of our members’. The article quoted the Soviet miners’ leader Mikhail Srebny as saying that 2.3 million roubles – equivalent to £2 million – had been collected for the NUM, including £1 million of hard currency in ‘golden roubles’. Soviet miners had given up two days’ pay for their British comrades, so it was said. ‘The figures’, the Sunday Mirror explained triumphantly, ‘show a discrepancy of around £1 million. No one is saying what happened to the missing money.’ The story was written by Alastair Campbell – then Neil Kinnock’s closest friend and ally in Fleet Street, later Tony Blair’s press secretary – while the main source for the British end of the tale was transparently Margaret Thatcher’s devoted spin-doctor, Bernard Ingham. But, like John the Baptist, this was only a harbinger of greater things to come. The next day, the Sunday paper promised its readers, Maxwell’s daily would treat them to the ‘authentic inside story’ of how Scargill also took Libyan money – and ‘how he used some of it for personal transactions’.4

‘THE FACTS’

On Monday, 5 March, the campaign began in earnest. ‘Scargill and the Libyan Money: The Facts’, the legend on the Daily Mirror’s front page proclaimed. The Mirror’s ‘splash’ headline – in two-inch-high letters – would later come to attract much ridicule and notoriety, but it was treated with the utmost seriousness at the time. Across the top of the page, next to the mandatory ‘exclusive’ tag, the principal charge was set out: ‘Miners’ leaders paid personal debts with Gaddafi cash.’ The following five pages were given over to the first set of ‘authentic’ revelations, under the joint byline of Terry Pattinson, the paper’s industrial editor, Frank Thorne and Ted Oliver. The most dramatic and damaging claim – and the one that Scargill later remembered ‘caused me real pain, real distress’ – was that the NUM president had used £25,000 of Libyan money donated for striking miners to pay off his own mortgage. As it turned out, the long-awaited Libyan connection merely added spice to the central ‘revelation’: the entirely unexpected accusation of embezzlement.5

Leaning heavily on the testimony of Roger Windsor, NUM chief executive officer from 1983 to 1989, the paper alleged:

Miners’ leader Arthur Scargill got £163,000 in strike support from Libya – and used a large chunk of it to pay personal debts. While miners were losing their homes at the height of the bitter 1984–5 strike, Scargill counted out more than £70,000 from a huge pile of cash strewn over an office table. He ordered that it should be used to pay back to the NUM his mortgage and the home loans of his two top officials.

These were Peter Heathfield, the union’s elected general secretary, and Windsor himself. The Mirror traced the story back to the controversy during the strike over Windsor’s dramatically publicized trip to Libya for the NUM, when he was filmed meeting Colonel Gaddafi. Scargill had always denied taking money from the Libyan regime, but here was Roger Windsor himself now revealing the ‘incredible cloak-and-dagger operation to bring a secret hoard of Libyan money into Britain’. The cash had been ferried over from Tripoli in suitcases, it was said, on three separate trips by the man first revealed as a Libyan go-between in 1984. This was Altaf Abbasi, a ‘mysterious Pakistani businessman … [who] had been jailed for terrorism in Pakistan’. Windsor was then supposed to have collected the money from Abbasi on three separate occasions in Sheffield and Rotherham in November 1984. Finally, Windsor had – according to the Mirror – brought the total of £163,000 (more than £443,000 at 2012 prices) into Scargill’s office on 4 December 1984 on the NUM leader’s instructions. Scargill explained he was anxious to see the union’s accounts ‘cleaned’ in readiness for the imminent takeover by a court-appointed receiver. He was worried in case the ‘receiver or sequestrator would find them to be … “not entirely one hundred per cent” ’. The NUM president had then counted out three heaps of banknotes, the former chief executive alleged, to settle the three officials’ outstanding ‘home loans’: £25,000 to clear his own mortgage, ‘around £17,000’ for Heathfield’s ‘home improvements’, and £29,500 to clear Windsor’s own bridging loan advanced earlier in the year. A further £10,000 was also set aside to pay off legal expenses run up by the union’s Nottinghamshire area.

It was a devastating series of allegations, which seemed to be thoroughly corroborated by other witnesses: Steve Hudson, the NUM’s finance officer during the 1984–5 strike, who remembered being called to Scargill’s office to pick up the cash for the repayments and provide receipts; Jim Parker, Scargill’s estranged driver and minder, who confirmed taking Windsor to meet the Pakistani middleman for at least two of the cash ‘pick-ups’; Abbasi himself, who described three trips to Libya to collect the money from ‘Mr Bashir’, head of the Libyan trade unions, and his subsequent deliveries to the NUM chief executive; Windsor’s wife Angie, who remembered the Libyan cash being stored in the family house; and Abdul Ghani, who said he had acted as a witness at two of the cash handovers for his friend Abbasi.

The story could scarcely have looked more damning. The problem was not so much the confirmation that the NUM had secretly taken donations from the Soviet Union and Libya. For all the huffing and puffing, such funding had been widely assumed, despite the NUM leadership’s denials. And in the case of the Soviet Union, the ‘troika’ of strike leaders – Scargill, Heathfield and McGahey – had all openly pressed for cash support in 1984. But the revelation that two of the miners’ strike troika had apparently had their hands in the till was something else entirely. This was a real scoop. However much his critics disliked his politics and his leadership style, nobody imagined Scargill was personally corrupt. The same was true of the widely respected Heathfield. But now it seemed that the Robespierre of the British labour movement, the sea-green incorruptible, the trade-union leader that ‘doesn’t sell out’, had been exposed as a grubby, silver-fingered union boss lining his pockets at his members’ expense.

On ‘Day One’ of the Mirror campaign, the flagship of the Maxwell empire carried a special editorial, personally signed by ‘Robert Maxwell, Publisher’. With the imprimatur of the great man himself and headlined ‘Scargill’s Waterloo’, the Mirror conceded that the paper had never in fact supported the 1984–5 miners’ strike. ‘But there is no gloating on our part in exposing how hollow it was … the hypocrisy of the NUM’s disastrous leadership’ was only now revealed. ‘Some shady manoeuvres’, the man once described by government inspectors as unfit to run a public company went on, ‘were probably inevitable’. But unions had to be ‘open and honest, both with their members and with the public’. The Mirror’s revelations about the NUM ‘show that it was neither’.6

That night, the miners’ leaders’ pain was piled on in spadefuls as the Cook Report went into action before an even bigger audience. The saga of the Libyan money, home loans and Altaf Abbasi’s international courier service was rehearsed in loving detail. As Roger Cook – the man who had unmasked a thousand small-time swindlers and petty crooks – described the scene in the programme’s voice-over: ‘It’s December 1984, halfway through the strike, and the three men who run the NUM are counting out the cash to pay off their personal loans when many striking miners were losing their houses.’ But the Cook Report took things a stage further, wildly upping the ante on the size of the supposed Libyan slush fund. The Libyans had not only donated £163,000, the programme declared. According to Altaf Abbasi, they had also come up with an extra $9 million – something he had apparently not thought fit to mention to the Daily Mirror. This huge sum had been made available, he said, for ‘hardship purposes only’. Most of the money had then been returned during the previous three months after an unexplained ‘official inquiry’.

There was more. At a secret meeting with Abbasi in Roger Windsor’s house, it was said, Scargill had asked the Libyans to provide guns for his personal use. The former chief executive recalled: ‘He wanted … a revolver for himself, a little ladies’ revolver that he could keep in the car and a pump action shotgun.’ The viewer was then informed by Cook that ‘Mr Scargill apparently asked other people for guns too’ – we were not told who – ‘but in Altaf Abbasi’s case settled for the money instead.’ The programme also made hay in passing with a Soviet strike donation of one million dollars – or pounds, it was not entirely clear which – that Windsor claimed had been paid into a Warsaw bank account with Scargill and Heathfield as sole signatories. Cook explained that the money had earlier appeared in an NUM account in Switzerland but been returned on Scargill’s instructions, ‘officially to keep it out of the hands of the sequestrators’. The clear implication was that the cash was diverted to finance Scargill’s own private pet projects.

Stories were recounted of the sinister rewriting of NUM executive minutes, ‘strange transactions’, dodgy bank accounts, and the misuse of the International Miners’ Organization for Scargill’s ‘Machiavellian machinations’. Jim Parker, lifelong communist, Scargill bodyguard, driver and buddy, appeared on screen to insist that the widely reported police assault on Scargill at Orgreave in the summer of 1984 had been a propaganda fraud. ‘If the truth were known … he actually slipped down a bank.’ When he had been told about Scargill’s mortgage scam, Parker declared, it was the last straw. ‘That’s something I shall never forgive him for.’7

The Mirror, it has to be said, did at least print edited highlights of the NUM’s denials, if only to insist that the paper was able to ‘expose the big lie’. Roger Cook relied instead on the ‘doorstepping’ technique which made the heavyweight New Zealander’s name. ‘Did you or did you not’, he demanded of the miners’ president as Scargill drove off from his bungalow outside Worsbrough Dale near Barnsley, count out ‘bundles of cash for you, for Peter Heathfield and for Roger Windsor on your office desk?’ In the view of Roy Greenslade, the Mirror’s editor, the scene of Scargill repeating mechanically through his car window ‘If you’ve got any questions … put them in writing, send them to me and I’ll make...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to the Fourth Edition

- Introduction: The Secret War Against the Miners

- Chapter One: Operation Cyclops

- Chapter Two: A Hidden Hand

- Chapter Three: Dangerous Liaisons

- Chapter Four: The Strange World of Roger Windsor

- Chapter Five: All Maxwell’s Men

- Chapter Six: Moscow Gold-Diggers

- Chapter Seven: Stella Wars

- Conclusion: Who Framed Arthur Scargill?

- Postscript to the Fourth Edition

- Notes

- List of Abbreviations