- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What makes the city of the future? How do you heal a divided city?

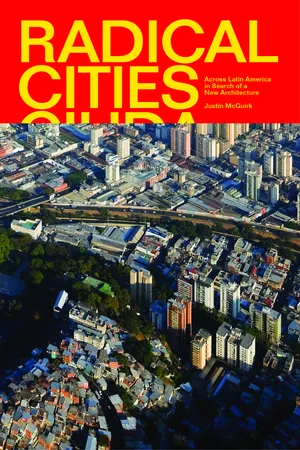

In Radical Cities, Justin McGuirk travels across Latin America in search of the activist architects, maverick politicians and alternative communities already answering these questions. From Brazil to Venezuela, and from Mexico to Argentina, McGuirk discovers the people and ideas shaping the way cities are evolving.

Ever since the mid twentieth century, when the dream of modernist utopia went to Latin America to die, the continent has been a testing ground for exciting new conceptions of the city. An architect in Chile has designed a form of social housing where only half of the house is built, allowing the owners to adapt the rest; Medell?n, formerly the world's murder capital, has been transformed with innovative public architecture; squatters in Caracas have taken over the forty-five-story Torre David skyscraper; and Rio is on a mission to incorporate its favelas into the rest of the city.

Here, in the most urbanised continent on the planet, extreme cities have bred extreme conditions, from vast housing estates to sprawling slums. But after decades of social and political failure, a new generation has revitalised architecture and urban design in order to address persistent poverty and inequality. Together, these activists, pragmatists and social idealists are performing bold experiments that the rest of the world may learn from.

Radical Cities is a colorful journey through Latin America-a crucible of architectural and urban innovation.

In Radical Cities, Justin McGuirk travels across Latin America in search of the activist architects, maverick politicians and alternative communities already answering these questions. From Brazil to Venezuela, and from Mexico to Argentina, McGuirk discovers the people and ideas shaping the way cities are evolving.

Ever since the mid twentieth century, when the dream of modernist utopia went to Latin America to die, the continent has been a testing ground for exciting new conceptions of the city. An architect in Chile has designed a form of social housing where only half of the house is built, allowing the owners to adapt the rest; Medell?n, formerly the world's murder capital, has been transformed with innovative public architecture; squatters in Caracas have taken over the forty-five-story Torre David skyscraper; and Rio is on a mission to incorporate its favelas into the rest of the city.

Here, in the most urbanised continent on the planet, extreme cities have bred extreme conditions, from vast housing estates to sprawling slums. But after decades of social and political failure, a new generation has revitalised architecture and urban design in order to address persistent poverty and inequality. Together, these activists, pragmatists and social idealists are performing bold experiments that the rest of the world may learn from.

Radical Cities is a colorful journey through Latin America-a crucible of architectural and urban innovation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Radical Cities by Justin McGuirk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

From Buenos Aires to San Salvador

de Jujuy: Dictators and Revolutionaries

On 11 December 2010, the homepage of Argentina’s La Nación newspaper was dominated by a terrible, sublime image. It depicted a group of figures standing around a supine body. In the twilight, most are black shadows, but two men are picked out in centre stage as if by a spotlight: one, shirtless and flabby, is leaning over a fallen comrade whose head is bathed in blood. The image has the stark drama of Caravaggio’s Beheading of Saint John the Baptist – the price of a moment’s violence revealed in the gloom. However, the mise en scène here is a park near a housing estate called Villa Soldati, in a southern suburb of Buenos Aires. This is the aftermath of a pitched battle between residents and homeless immigrants squatting in the park. Several people were killed or wounded that day, thanks to a cocktail of social tensions and Nimbyism. And the roots of it all lay in the failure of the government’s housing policy – a failure that stretches back decades.

Buenos Aires is a city of political theatre. Party politics is played out in the street by means of weekly demonstrations and rallies by one group or another – a workers’ union here, the Peronist Youth Movement there. Demonstrations take on a carnival atmosphere, with songs and the banging of drums that in other countries would accompany the weekend march to the football stadium. Porteños, as the citizens of this port city are called, live their politics with the same passion as their sport, especially since the economic crisis of 2001, which radicalised a generation and put the nation on guard against the ineptitude of its leaders. The greatest political drama since the national bankruptcy took place six weeks before the running battle at Villa Soldati. Néstor Kirchner, the former president, husband of the incumbent president and a talismanic figure, died of a heart attack. The nation mourned loudly and publicly, thronging the avenues feeding into Plaza de Mayo for the chance to file past his casket in the Casa Rosada. The graffiti, more often than not political in Buenos Aires, took on a mystical quality: it became common to see ‘Néstor vive’ (Nestor lives) scrawled on city walls.

Kirchner, to his credit, believed in social housing. After more than a decade of neoliberal policies that finally brought the country to ruin, here was a man with a social agenda. In 2004, Kirchner’s government launched the Programa Federal, the first social housing programme in fifteen years, which set out to build 120,000 houses nationwide over two years, to the tune of $7 billion. And yet this and subsequent programmes, at least in Buenos Aires, failed to slow the growth of informal housing. The villas miseria, or slums, continued to expand. The most notorious of them is Villa 31, noteworthy not so much for its size – it is home to roughly 120,000 people – as for its location in well-heeled Retiro, in central Buenos Aires, where it is an all too visible symbol of the failure of successive governments to provide adequate housing for the poor.

The violence at Villa Soldati was another high-profile symptom of that failure. It was sparked by tensions between the residents of Villa Soldati and squatters in the neighbouring Indoamericano Park, which was aptly named, since it was largely Bolivian and Paraguayan Indians who had set up camp there in the hope of eventually turning tents into houses. Essentially it was a battle between the housed – who didn’t want ‘their’ park turning into another slum – and the homeless. These newcomers had not had the benefit of the kind of mass housing programmes that were such a major feature of Argentina’s political agenda in the 1970s, when Villa Soldati was built.

Viewed from the nearby flyover, Soldati is a rather extraordinary-looking place. It has a dystopian, retro-futuristic air, a blocky termite mound rising up towards angular water towers that poke up like periscopes. Designed for just over 3,000 people, it was merely one of numerous mega-projects built immediately before and during the military dictatorship that took control of the country in 1976. The most infamous of them is Fuerte Apache – or Fort Apache, a nickname apparently taken from the Bronx police station in the 1981 movie of the same name – built to house 4,600 people and now a dangerous slum. Like a rotting modernist casbah, it’s a no-go area rife with gangs and drug crime. From this cauldron emerged a minor miracle, the footballer Carlos Tévez, known as ‘El Apache’, who escaped his fate to earn millions at Manchester City and Juventus.

If Fuerte Apache is potentially life-threatening to the outsider, then Soldati is merely threatening. But not all of this generation of social housing deteriorated quite so drastically. The biggest of the estates in this part of the city, Villa Lugano, is still in perfectly serviceable condition. Designed in 1975 for 6,500 people, it was a paragon of European housing ideas from the previous decade. Influenced in particular by British brutalists such as Alison and Peter Smithson, Lugano’s megablocks have parades of shops raised one storey off the ground – a faithful rendition of that much-loved modernist trope, ‘streets in the air’. Lugano is a perfect example of why streets in the air were often a bad idea: the actual streetscape is killed off, leaving boulevards lined with parking garages and blind walls.

One has to remind oneself that Soldati and Lugano were the products of what, in hindsight, now seems like a golden era. For all the political chaos that reigned in Argentina during the 1970s – when, before the military takeover, governments were falling to coups almost annually – it was still a time when the establishment broadly believed in the right to housing for all. It was certainly the last decade when architects enjoyed the support of the political elite. Indeed, it was the last decade that architects could legitimately claim to be fulfilling a social mission at all. Lugano may have been a cut-price copy of European ideas from the 1960s, but it still represented the best architectural thinking available at the time. Its architects, a practice called Marull, Pereyra & Ruiz, had a generous social vision in mind. In the library of the Sociedad Central de Arquitectos in Buenos Aires, I looked up the original plans in a faded architectural journal and discovered some artists’ impressions of the estate. They evoke a leafy modern citadel peopled with genteel types promenading or reading the paper – a place not unlike London’s Barbican. It’s a rather sweet vision, with no bearing on reality.

Conjunto Piedrabuena

Villa Soldati, Fuerte Apache and Villa Lugano are all on the southern fringe of Buenos Aires, dotted along the airport highway. But it was a fourth, in the same vicinity, that I decided to inspect more closely. Conjunto Piedrabuena had piqued my curiosity the first time I drove past it. It wasn’t just that it was a monumental relic of a bygone era; it was also not a piece of carbon-copy European modernism. This was oddly exotic. Its huge slabs were arranged in giant arcs, each connected by an octagonal tower like the eye at the centre of a panopticon. Despite the prison metaphor, there was something instantly compelling about the place and the way in which it commanded the landscape. With its scalloped bays, this was not the product of a simple modernist grid, this was more complex, more original. Its heft was softened somehow by the cracked walls and rusting shutters – yet more modern infrastructure become romantic ruin.

Conjunto Piedrabuena, named after the naval explorer Comandante Luis Piedrabuena, was designed in the late 1970s by the acclaimed practice of Manteola, Sánchez Gómez, Santos & Solsona. The architect in charge, however, was a young Uruguayan partner named Rafael Viñoly, who has gone on to be Latin America’s most commercially successful architect. A purveyor of corporate glass and steel, Viñoly is building one of the biggest and ugliest office towers in London. Originally dubbed the Walkie-Talkie, it was renamed the Fryscraper when it emerged that its curved facade had a habit of harnessing sunlight to melt cars. It came as something of a shock that this most corporate of architects had a pedigree in radical social housing. On the other hand, Viñoly’s career is also a perfect illustration of the shift in the architecture profession’s priorities over the last thirty years.

In a bakery at the base of one of Piedrabuena’s housing blocks, I meet Luciano. He is twenty-eight and short but with a stevedore’s build and ginger hair pulled back in a ponytail – he looks more Irish than Argentine. Framed against a fridge full of elaborately iced cakes, he tells me that he has lived here his whole life, along with three generations of his family. This will be true of most of the residents. Family ties are strong in South America, and perhaps more so in a place like Piedrabuena than in central Buenos Aires, precisely because it is isolated, out on the edge of the city. It is more like a small town in some ways, and thus follows more provincial ways. Most of Luciano’s generation will have lived here their whole lives, and there are few new arrivals from outside these family units. There have been plenty of new arrivals within them, however. These 2,100 apartments now house nearly 20,000 people.

The first wave of residents mainly belonged to the military or the police. That may not have been the intention when Piedrabuena was designed, but by the time it was inhabitable, in 1980, the military dictatorship had the country firmly in its grip – and housing was one way of buying loyalty. In fact the complex was never completed. This becomes apparent when we ride the lift up one of those striking octagonal towers. Of the fourteen floors in this block, the lift only stops at the fifth, eighth and eleventh. To save costs, there were no exits built into the lift shaft on the other floors, so most residents have to walk up or down a couple of flights from one of the exits. These were only the goods elevators – Luciano thinks the residents’ lifts weren’t even installed.

The complex is arranged into horseshoe-shaped coves overlooking what, now in summer, are rather parched green areas. The idea behind this arrangement was to organise the estate into neighbourhoods, as if to gather residents into the vast open arms of an embrace. Set within each curved rank of tower blocks are smaller ones, only four storeys high. The gap between these concentric curves creates shaded streets – a novel design that appears to work rather well. Elsewhere there are ramps at the foot of the blocks that were evidently designed to create amphitheatre-style seating for public events. That may be wishful thinking – the plazas have become impromptu car parks – but there are a couple of guys sparking up an oil-drum asado, or barbecue. At the centre of the complex, four raised walkways intersect above the main road. Luciano says that this is where kids in the estate head to when they’re being chased by the police, because it provides escape routes in four directions.

As we walk around I am conscious of people noticing us, keeping one eye on me, speculating on who I might be with my notebook in hand. But accompanied by Luciano, I have privileges. Everyone knows him here – everyone knows everyone. This microcosm is Luciano’s universe, the backdrop to his entire life. And he is proud of it. He has a tattoo of Piedrabuena across his lower back. This place is not just his second skin, it is his skin.

Luciano describes himself as an artist, and when he’s not doing odd jobs to get by he makes short documentary movies about the estate and posts them on YouTube. When I ask him how Piedrabuena has changed in his lifetime he responds with a catalogue of degradation. Most recently a staircase collapsed. Before that there was a gas explosion that left most of the complex without heating or water. You can see where it happened because one of the blocks is being supported by a timber buttress. The surfaces of the buildings are now criss-crossed with a circuit board of new gas pipes, and yet there are still 700 people left unserved.

To get anything done here, residents have to kick up a fuss: they demonstrate and barricade the roads. ‘But they’re workers,’ says Luciano. ‘They don’t have time or energy to do this for every basic need.’ And this is the story of how the great social housing projects went wrong – not on the architectural side, whatever one may think of such complexes, but on the political front. These megaprojects were treated as one-off expenses rather than long-term investments. Of course three decades with no maintenance would lead to degradation.

One can’t help but wonder what the future of this place is – or, rather, how long before that future comes to pass. There is a Pruitt-Igoe moment coming, the only question is when. Up underneath one of the water towers that crown the elevator cores, I notice whole chunks of concrete coming away. The walls generally are fissured. Piedrabuena is a prime site for lovers of modernist ruins. Inevitably, they shoot hip-hop videos here. Part of the appeal must be the murals. Luciano takes me on a tour of them, mostly passable renditions of art-historical masterpieces. Guernica and Hokusai’s wave are here, as are Dalí’s melting clocks. They are the works of a local artist known as Pepi, who has since moved out of Piedrabuena. In front of an ersatz version of Goya’s Execution of the Defenders of Madrid, Luciano says: ‘Normally if you want to see this painting you have to pay to get into a museum, but we can just sit here and enjoy it with a beer.’

‘Follow the money’

One Friday morning, thirty years after working on Piedrabuena, Rafael Viñoly is sitting in his London office trying to recall what it was like. He has just flown in from New York, and will be flying back there this very evening – a fact that, on its own, reveals one way in which the architecture profession has changed since he began his career. I want Viñoly to summon up the atmosphere of the late 1970s. I’ve set up Piedrabuena as a heroic failure, a relic of a time when political idealism and architectural ideology were aligned. But perhaps I am taking too rosy a view of a time when social housing still featured so prominently on the political agenda, and when politicians still trusted architects. From the point of view of today, with a clear view of the free market’s failure to provide an answer, it looks like idealism. Am I being naïve?

‘It was idealistic in the sense that we weren’t thinking about branding,’ says Viñoly. ‘We weren’t conscious of the buildings as a support for political advertising. The thing about Latin America, and Argentina in particular at that time, was that this subject was used as a political tool.’ Straight away, a picture emerges of social housing as a vote-buying exercise. ‘Follow the money,’ says Viñoly, like Deep Throat, the garage-lurking Watergate source in All the President’s Men.

If you follow the money in Piedrabuena’s case, the trail ends at a repressive dictatorship waging a ‘Dirty War’ against any form of political opposition. It’s a thought that rather takes the shine off the idea of social housing as an idealist product of the welfare state. Piedrabuena was a perfect example of housing being used to create a politically homogenous community – in this case of military and police families – loyal to the government.

One of the interesting features of the megablock approach to housing is precisely that sense of social engineering. The architects could have built the blocks smaller, creating less dense environments, but Viñoly recalls that they wanted to achieve a sense of the collective. In a country where the two primary sources of social cohesion were religion and the unions, the designers of Piedrabuena and other such estates were proposing another form of collective consciousness: the building block. Or, in Piedrabuena’s case, ‘the cove’, that horseshoe arrangement of blocks that constituted a neighbourhood. Viñoly says he still finds a dignity in this approach, and argues that the way he and his colleagues tried to create communities is ‘still valid’.

However, the housing programmes were more than exercises in buying political loyalty. From the early Perón era in the late 1940s onwards, the social housing industry became a major factor in driving the economy, creating employment and contributing a significant percentage of GDP. As such, they had a financial logic as well as socio-political motives, and of course in Argentina that logic was open to considerable abuse. The construction industry was hugely corrupt. Construction companies would inflate the budgets for the utilities, roads and earth-moving and pay off the politicians who got them the jobs. And then there were the conditions in which these projects were procured, with the architects working too fast and aiming the designs straight at the bottom line. ‘There was this incredible confusion of dictatorial, demagogic governments,’ says Viñoly, recalling his mid-thirties. ‘And you were working in an environment where if you stopped two minutes to think ethically, you probably couldn’t stand it.’

It gets worse. From 1977, the junta was on a mission to eradicate the villas miseria, which then accounted for 10 per cent of the population of Buenos Aires. The generals’ motives were largely political, since the slums were hotbeds of Peronist and socialist dissent, though they were also freeing up valuable land for development. After systematically dismantling the system of civil liberties, the regime set about evicting 200,000 people, accounting for 94 per cent of the city’s slums, often without even providing any alternative housing. This ruthless policy merely transplanted the villas miseria to the periphery or to other regions.

So the generation of housing estates to which Piedrabuena belongs was not even accessible to those most in need. Instead, they served the lower middle class. And this was often the case with social housing projects across Latin America. The loans and mortgages needed to afford a new state-provided apartment were beyond the means of the poorest. And when people were forcibly rehoused, it was always on the periphery, hours away from their jobs, in homes they struggled to pay for.

The fact that Viñoly can say that he still finds Piedrabuena ‘valid’ means that there is a thin residue of idealism left from his days designing social housing. But he’s thinking of the architecture, not the disastrous urban policy of building citadels on the periphery that were completely disconnected from the city. He is not thinking of a system that generated housing with no mechanisms for effectively managing or maintaining it, so that inevitably estates became formal slums, overcrowded and run-down. With the slums out of sight, the land freed in city centres was opened up to investment and speculation. Meanwhile, the investment in the new peripheries devalued with each passing year.

The paternalistic system of state-built housing was not always as politically ruthless or as corrupt as it was in Argentina during the dictatorship but, as we shall see, it was quickly abandoned when new ideologies came into play in the late 1970s and 80s. But if the top-down approach to urbanism was destructive and ethically compromised, are there any examples of bottom-up community building that are not slums? Are there any cases of self-organisation with urban aspirations, social amenities and government recognition?

In the far north of Argentina, I encountered a strange yet radical example.

Túpac Amaru

In Villa Lugano I noticed an insignia painted on a wall. More than graffiti, it was a logo several feet across depicting a man’s head in what resembled an American pilgrim’s hat, the crown of the hat forming the apex of the letter ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. From Buenos Aires to San Salvador de Jujuy: Dictators and Revolutionaries

- 2. From Lima to Santiago: A Platform for Change

- 3. Rio de Janeiro: The Favela Is the City

- 4. Caracas: The City Is Frozen Politics

- 5. Torre David: A Pirate Utopia

- 6. Bogotá: The City as a School

- 7. Medellín: Social Urbanism

- 8. Tijuana: On the Political Equator

- Acknowledgements

- Index