- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

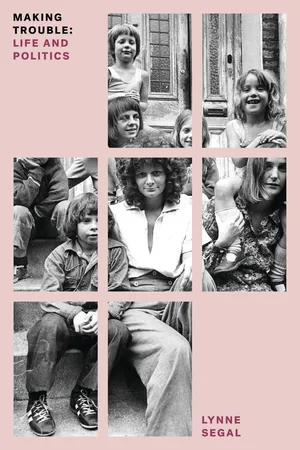

What happens when angry young rebels become wary older women, ageing in a leaner, meaner time: a time which exalts only the 'new', in a ruling orthodoxy daily disparaging all it portrays as the 'old'? Delving into her own life and those of others who left their mark on it, Lynne Segal tracks through time to consider her generation of female dreamers, what formed them, how they left their mark on the world, where they are now in times when pessimism seems never far from what remains of public life. Searching for answers, she studies her family history, sexual awakening, ethnic belonging, as well as the peculiarities of the time and place that shaped her own political journeys, with all their urgency, significance, pleasures and absurdities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Making Trouble by Lynne Segal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Strictly personal

It is all too easy, I find, to tell one’s life as stand-up comedy; all too tempting to amuse with anecdotes which, in their well-rehearsed familiarity, smother self-doubt with self-display. But comic turns are not the usual mode of entry for tales of political belonging, though they might resonate well enough with a few of their less effective tendencies. Nevertheless, it was the appeal and significance of certain shared collective goals that at times helped me move beyond the needy, performing self that emerged from my childhood, forever in search of attention, warmth and affection.

Where did it begin? Of course, literally, and for most women so crucially, it starts with our mothers. That sometimes peculiar presence, the father, was usually somewhere in the background when I was a child; behind the scenes, though in my case much too obtrusive, unwelcome, redundant, disturbing. Feminist reflections still provide the only rational outlook for any shrewd woman. However, I’ve thought for a long time, and heard others agree, that the particular affiliations we espouse vary just a little according to which parent we were closest to, which was most admired, feared, mourned, or seemed in need of protection. As Beauvoir said, ‘the great danger which threatens the infant in our culture lies in the fact that the mother to whom it is confined in all its helplessness is almost always a discontented woman’.1 Discontented? This is far too weak a word to describe my mother’s bitterness and scorn, reciting the litany of my father’s sins.

In the beginning

My parents were both medical doctors, although my mother’s training and achievements were far more distinguished; she had qualified as a surgeon – only the second woman in Australia to do so. From early on she had the busier surgery, much to my father’s annoyance, and before too long she also had the higher remuneration, the greater admiration from patients and colleagues, while working hardest to secure them all. My father’s habitual irritability (which I thought manifest in his strange, jumpy, nervous tics); his miscellaneous infidelity; his small cruelties, hurtful teasing, enduring selfishness, seeming incompetence; these formed the background of my childhood. PAY BY INTERCOURSE was the graffiti my mother said he made her – made her? – scrub off the high walls around our large and ugly suburban house, which doubled as his surgery. ‘What happened to the patient?’ I asked. ‘He had her certified, of course,’ she replied; well, of course. ‘I always knew how to get a woman with an infertile husband pregnant – send her to your father,’ was another of my mother’s scathing asides (though no illegitimate siblings ever surfaced).

Was he really that bad? My sister thought so. My uncle thought so (though he too heard his sister’s shocking stories). I can summon up few contrasting images of him, nor did others praise him in my hearing, to mitigate our mother’s bile: ‘I cried myself to sleep every night after my marriage,’ she said. I tried to sleep every night, praying – literally, to a God that I did not believe in – that my father would stop making her so unhappy, stop being so bad-tempered, stop arguing with her. Things never changed. Nor was it only through my mother’s tales that I shrunk back from his way of being in the world. There was also the tenor of his strangely sadistic humour, face brightening, it seemed to me, only when he could manage to upset one of us: attempting to provoke jealousy between his children, teasingly ridiculing us before friends, trying to heighten our fears of pain before injections or other painful medications. Perhaps it was a type of humour he had known, which I just wasn’t ready for. I cannot say that he had no redeeming features, no ambiguities or goodness; I can only say I did not know them. My brother is a little less critical, believing that our parents were exceptionally badly matched. In his view, our father, the oldest son of first generation, impecunious eastern European immigrants, felt rebuffed and diminished by a wife who was clearly cleverer than him, and better loved by the world, if not by him.

This wife, our mother, was the once cherished and distinguished daughter of far from wealthy but highly regarded second generation Anglo-German Jews, already at the heart of Sydney’s very respectable Jewish community. My father, from a poorer background of Lithuanian Jews (then seen as more foreign, or ‘oriental’), arrived in Australia in the early twentieth century. However, I learned absolutely nothing about any of this from my parents. They never spoke of their childhoods, nor of the birthplaces of our Ashkenazi forebears, in Prussia, Poland, Lithuania and Britain, although I now see the bitter tensions I was born into as perhaps, in part, condensations of some of that earlier racist friction, fear and defensiveness at a time when, unknown to me, genocidal anti-Semitism had just engulfed most of Europe.

Mother’s dutiful daughters, my sister and I had no positive feelings for our fault-finding, quarrelsome father. Unknowingly, we repeated the story of his sisters, who had despised their own father (apparently also for his philandering, and their mother’s consequent bitterness), refusing to speak to or visit him, even on his deathbed. (This grand-father was another absent presence in our life, along with our maternal grandfather, who died before we could ever know him.) Today, I simply wish I had ways of fathoming what it was that made our father so completely unable to show affection for his daughters. He seemed barely able to approach us, let alone touch us; he did not visit me in hospital following my childhood asthma crises, even when spotted calling upon one of his patients within the very same building. I can only speculate on the demons that may have stalked that infant Jewish boy growing up in a family with parents who were apparently so harshly alienated from each other that they only communicated by using their children as intermediaries.

Born in Cape Town in 1904, my father arrived in the slums of Sydney in 1906 with parents who had fled persecution in eastern Europe. He made his way laboriously out of unhappy, far from respectable beginnings (about which he remained forever silent, forever ashamed) into Sydney’s then still conspicuously anti-Semitic, professional middle class. His unmarried sisters remained factory workers all their working lives, another source of embarrassment to him. What is more surprising, perhaps, is that as children we learned nothing at all about our mother’s background or childhood (apart from her prestigious educational accomplishments), although her much-loved father, Alfred Harris, had been a key, indeed pivotal, figure in sustaining Australia’s Jewish community for most of his life.

Buried pasts

‘Are we Jewish?’ my brother recalls asking our non-Jewish housekeeper as a child. ‘Yes, I suppose you are, dear, but you don’t have to tell people,’ she replied. That must have been one of the very few sentiments she shared with her arch-rival, our mother, who also thought it best, I now realize, to divest herself of any blatant signs of Jewishness. Our mother’s passionate atheism, from which she never lapsed, must have helped distance her from home-grown anti-Semitism, not to mention the nightmare of Hitler’s slaughter of the Jews of Europe. (No known relative of ours was killed.) With her strict rationalism, she thought that only an imbecile could believe in any God, let alone one who allowed such barbarism to befall his self-appointed chosen people. Less judgementally, I find it hard not to agree.

Many Jews thought similarly at that time. All religion is folly, Richard Wollheim recalls his father declaring angrily in Britain in the 1940s, insisting that to classify people as Jews ‘had no basis in scientific fact’, but was merely the first step on the way to mistreating them. As a child, Wollheim did not even know that his father was Jewish, although he later discovered that he had spent a great deal of time and money rescuing not only his own relatives, but also friends and even acquaintances from Hitler’s lethal clutches.2 In much the same way, my mother, although dutifully attending synagogue in her young life, later came to regard all religion as absurd, even evil. My parents were not the only Jews then making their homelands in ‘new’ worlds who came to see complete assimilation as the only answer to it all. My mother’s brother expands on this view today, making me realize that, despite little blatant discrimination, anti-Semitism was a frightening threat in my parents’ early life in ways it has simply never been in mine.

Indeed, till very recently, Jewish identity would remain a largely empty category. My father, feeling only shame for his impoverished past, focused instead on various recreational activities and hobbies, none of which linked him to any Jewish communities. Along with so many of the people and places she encountered, my mother, I see in retrospect, had internalised not only the intense racism of ‘white’ Australians, but also their disdain for ‘foreign’ Jews. The home-grown images etched in the psyches of every Australian child of her generation came from its best-loved fairy tales, written and beautifully illustrated by May Gibbs, in which the light and fluffy Snuggle Pot and Cuddle Pie lived forever in titillating fear and dread of the dangers threatened by scary, thick-lipped, dark and hairy, Big Bad Banksia Men.3 My mother did not like us to spend time in the sun, not yet expressing a fear of its ultra-violet rays, but rather in thrall to light skin. My mother’s more specific distance from Judaism, I now suspect, was also an aspect of her lifelong eagerness to fit in and be well-liked and acceptable, shored up by a positivistic rationality aligned with her medical studies at Sydney University and the general intellectual climate she encountered at the time. Her heroes were always the great humanists, Bertrand Russell and George Bernard Shaw. The flight from her family roots was also encouraged by my mother’s shame at the emotional frailty of her own mother (my grandmother, who suffered, I heard only recently, from serious bouts of depression), as well as embarrassment at her father’s relative poverty, compared with the wealthy Anglo-Jewish establishment he was part of. These wealthy Jewish families were eager to court her, so she told us, only after she graduated at the top of her year in medicine and was, briefly, a celebrity. Finally, her distance from her Jewish past was also, no doubt, amplified by her enduring marital disappointment, after a lavish Jewish wedding entered into, she said, at the behest of my grandfather when he discovered his daughter ‘in bed’ with the man who would become my father.

It is only after my mother’s death, in my middle age, that I can grasp something of the sadness and loss in her repudiation of her own past, with its very particular and significant Jewish heritage. As an unregenerate bragger, there was much she might otherwise have been proud to affirm. In childhood she was the devoted daughter of a self-educated man, who spent almost all his life attending to Australia’s Jewish community as its writer and reporter. Alfred Harris, leaving home and school at fourteen, managed with his father, Henry Harris, to set up the first successful Jewish weekly in Australia, The Hebrew Standard, in 1895. Against enduring odds, he edited the newspaper for almost fifty years – despite the chronic financial worries, overwork and emotional exhaustion that many thought helped to shorten his life. He is described in Australian Jewish history books as an unusually gentle, humane and selfless man, who saw his life work as preserving the spirit of orthodox religious life, while encouraging both friendship across all faiths and patriotic citizenship from Jews, in whatever countries they lived.4 He also used his paper, from the early decades of the twentieth century, to oppose the growth of political Zionism, a project he believed to be ‘unjust, dangerous to a degree, even cruel in its inevitable consequences and, after all, unattainable.’5 Such passionate anti-Zionism would lead Australian Jewry to spurn much of my grandfather’s legacy once Jewish support for Israel became hegemonic after the state’s founding, in 1948. ‘To live in hearts we leave behind, is not to die,’ his friend and mentor, the first Australian-born prime minister, Sir Isaac Isaacs, said in his appreciation of Alfred Harris after his death in 1944: ‘I say unaffectedly his passing has left a void in my life’s experience beyond my power of adequate expression.’6

That my mother was not able to express any appreciation of her father’s legacy, I now think, added to her abiding sense of inner emptiness, her failure to feel good about herself or her life, despite her considerable achievements. It was not easy being a successful professional woman in mid-twentieth-century Australia, and many women I would later meet described my mother as an inspiration to them. Nevertheless, a sense of bitter loss and futility dogged her. Whatever its intricate source, this sense of emptiness was something I too seemed to absorb from my mother, or often feared I had. It would be over fifty years before I came to reflect upon the nature or significance of my family’s Jewish heritage. As ever, it was politics that finally led me back to the question of what it might mean to be a Jew, in a world where our putative ties with Israel and its continuing Zionist project seemed to matter more than ever, aligning me with the buried maternal legacy. That ambivalent Jewish identification, however, would prove just as elusive as the various other identities I have acquired or grappled with throughout my life.

Household shadows

Back in the 1960s, I had trouble accepting any of the roles that awaited me on leaving school. It was not merely that many women coming of age in the Sixties had no inspirational guides or mentors – we had the reverse: danger signs everywhere, anti-models galore. Even our mothers, and not only my mother, wanted our lives to be different from their own. Why had so many of them become bitter, or disenchanted, with their lot? It’s a complex story, which I’ll return to again, encompassing the aftershock and disruptions of wartime, the orchestrated charade of a supposedly ‘conflict-free’ peacetime, and the extraordinarily repressive nature of mid-century Australian society. I have come across its strange legacy over and over, the sham barely concealing the gloomy truth inside those Fifties families. Happy families are not all alike, but an unhappy family is certainly unhappy after its very own fashion. My mother was not a bored and frustrated housewife, unable to put her skills, training and intellect to use (like the mothers of many of my friends). She was an admired, successful, endlessly busy gynaecologist, doing a job she seemed to enjoy. Always alert for that phone call that would whisk her away from the argumentative husband, three obedient children and the working-class mistress our father had installed as ‘housekeeper’ (just before her marriage), it was coming home that was her problem. The phone call usually came. That was my problem. I was always happiest when she was somewhere around, at least when she was not too unhappy, and she could ignore us all as she tried to impress some – any – passing visitor, worker, or stranger. Another, better world always beckoned, where she could forget her conjugal miseries.

It beckoned to me too. ‘We couldn’t take you out,’ the same housekeeper-cum-nursemaid told me, years later, ‘you’d just toddle up to some stranger and wander off with them.’ Rather sensible little steps, it might seem, when her other weird tales included leaving me most of the day alone in my cot, upstairs on the veranda, pulling threads out of my nappy; waving eagerly at those passing strangers out of the window, once I was able to stand. Can I believe these stories? Have I imagined them? Where was my brother, only a year older? I do know that from the beginning, in the housekeeper’s eyes, I took after her rival, that mother of mine: my red hair – a sign of bad temper, she said – was the maternal lineage. The jet black locks of my brother and my sister (born fourteen months after me) were shared with our father. They were the two children with whom the housekeeper always, and quite obviously, enjoyed mutual affection, never with me. Fixated as I was on the fleeting maternal presence, I didn’t seem to mind, although scolded by the housekeeper as my mother’s favourite. ‘Why do they say I am your favourite?’ I questioned my mother (who would invariably visit me in hospital whenever I was rushed there after some bronchial crisis). I asked the question knowing, of course, and agreeing also, that only my brother, the budding ‘genius’, could hold that position. ‘Well,’ she replied, or I dreamt she did, ‘you seem to need me most.’

Such were the protocols of the life I recall in this particular unhappy family. But, when not squabbling, I played contentedly enough with my younger sister. I looked forward to the evenings when my mother, in her soft, flowing dresses, put us to bed or, at the very least, arrived at the bedroom door of the girls’ room, to blow us both huge, noisy kisses. I was usually happy in school, occasionally the teacher’s pet, cheerful with classmates. As the children of two doctors, we were received with kindly approval most places we went. I looked up to and admired my clever brother, who was indulged by all (apart from his peers at school) as a gifted, exceptional child, allowed to say or do whatever he liked at home. For the most part, that involved staying in his room, in pyjamas, hairgrip securing his long front lock, while absorbed, apparently contentedly, in his books. In the evening, my mother spent much of her time reading my brother’s homework or listening to him run through or recite by heart things he was learning – perhaps a play by Shakespeare, Russell’s mathematical proofs of modal logics, a Tennyson poem. After puberty, we three children spent most of our time outside school doing homework, or at least, in my own case, often pretending to. It afforded me much time for daydreaming, usually some mildly masochistic, erotic reverie. We did not live in the vicinity of the schools we attended, so had no local friends. At the weekend, our mother might take us to the beach, or on some longer, pleasant trek.

It was at night that my troubles often started: I found it hard to sleep, frequently wheezing and fighting for breath in bed; I was always frightened of the dark, sensing a threatening presence in the air which I felt in some mysterious way linked up with my father, in league with the housekeeper. Yet, even while confronting these bad spirits, it was the good ones emanating from my mostly absent mother that kept me sane and, so often lost in pleasurable daydreams, happy enough – despite suffering chronic asthma attacks from the age of four. ‘It’s because she’s spoilt by her mother’, ‘she only puts it on to get attention’, the two adults who frightened me would pronounce. These two, my father and the housekeeper, were responsible, as I saw it, for packing me off alone to the country at five, or rather, accompanied only by another of my father’s mistresses (how did I know that? I think my mother told me) and then to boarding school for four years at eight. Neither daft diagnosis of my illness, nor the various banishments from home, made a jot of difference to my lifelong asthmatic condition. My mother too, though usually kinder, shared the view that there was something shameful in suffering from an illness that could not be cured by antibiotics: ‘tell them you have bronchitis’ was her instruction, an early lesson in the art of duplicity.

I was thought to be an ‘oversensitive’ child, far too easily disturbed by any news of road crashes or other disasters, over-reacting to books or films that were even mildly scary or sad. Ironically, though, my own daily reveries always involved my undergoing and surviving s...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Preface to the 2017 edition: How do we join the resistance?

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1. Strictly personal

- 2. My Sydney sixties

- 3. Hearing voices

- 4. Escape into action

- 5. Political timelines

- 6. When sexual warriors grow old

- 7. As a rootless cosmpolitan: Jewish questions

- 8. Ways of belonging

- Notes and references

- Index