![]()

PART I

THE COLONIAL SETTING

![]()

CHAPTER I . A SUMMARY VIEW OF THE EASTERN SEABOARD IN 1750

The first permanent English settlement on the Atlantic Seaboard was begun in 1607. During the following century and a half the process of colonization resulted in the emergence of the thirteen colonies that were subsequently to join together to form the United States. What had begun as a handful of settlers insecurely seated on a forbidding neck of land had become, by 1750, a more or less continuous belt of settlement stretching for a distance of over 1,000 miles, and containing about 1,171,000 inhabitants.1

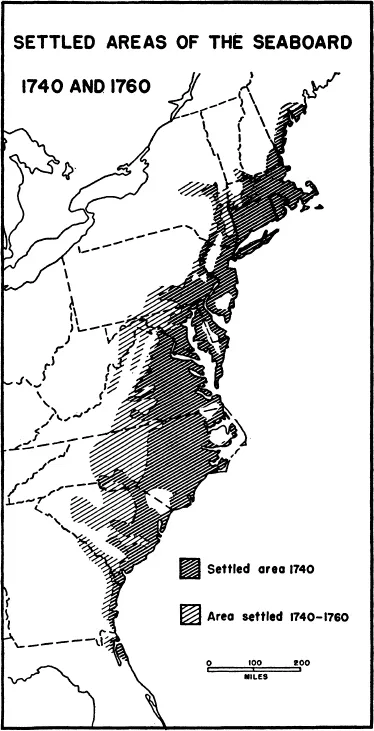

Each one of the thirteen colonies developed its own marked individuality and its own internal diversity. The distinctiveness of the colony of North Carolina is the chief subject of the chapters that follow. To place its unique qualities in an appropriate perspective it is necessary first to survey the geography of the other twelve colonies at the middle of the eighteenth century. Traditionally, historians have distinguished between the New England, Middle, and Southern colonies, a division which will serve as a suitable framework for this introductory survey of the geography of the colonial scene in 1750. Fig. 1 is a guide to the distribution of the areas settled and illustrates the expansion that was taking place around the middle of the century.2

NEW ENGLAND COLONIES

New England in 1750 contained about a third of the total population of the mainland colonies. The proportion of Negroes in this population was small, since slavery was practiced on a much smaller scale than in the Southern colonies. The prevalence of townships in the region contributed much to its individuality. The township system was used as a method of survey, as the basis of land granting, and as a form of local government; it gave rise to distinctive settlement patterns that still persist as a feature of the area.

FIG. 1

Most of the inhabitants of New England’s townships were small farmers. They grew a variety of crops and produced quantities of beef, pork, and livestock for export, as well as food and provisions for local villages and towns. Other New Englanders earned a living by engaging in commerce, or shipbuilding, or manufacturing, or fishing, or by exploiting the forest resources, or by combining two or more of these occupations. Occupational diversity was perhaps more common here than elsewhere along the Eastern Seaboard. But in this, as in other respects, there were considerable differences among the four New England colonies.

In Massachusetts, by 1750, settlement had spread far from the original coastal centers, both to the west and north. Settlements in the form of single dispersed farms had increased and it would be difficult to say whether these or the compact farm villages were the more typical form of settlement. Not all of the inhabitants were rural folk, and among the urban settlements in the colony Boston was pre-eminent.

The metropolis of Boston had a population of about fifteen thousand by the middle of the century. It was still of major importance as a commercial and shipping center of the overseas British Empire and the city’s merchants carried on trade with many ports on both sides of the Atlantic. It was also the focus of the political, economic, and cultural life of Massachusetts. Many of the products of Massachusetts’ fields and forests were exported from Boston, as were the products of its distilleries, iron works, and shipyards; the population of the city furnished an important consuming market for its agricultural hinterland, and additional grain was imported from other colonies to augment the food supply. Salem, too, was an important urban center in Massachusetts; founded earlier than Boston, it remained primarily a seafaring community, whose members were chiefly concerned with shipbuilding, fishing, and maritime trade.

New Hampshire, by contrast, did not have any large or important urban center. The total population was less than twice as large as Boston, and it was the least populous of the New England colonies. The utilization of forest resources was of special significance in New Hampshire, where the drastic harvesting of the magnificent stands of white pine was underway and constituted the basis of an important trade in ship timber. Most of the people, however, were farmers. The undramatic but steady process of extending the settled area absorbed much of their time and labor, and gradually transformed the landscape.

In Connecticut, signs of the dualism that still characterizes this area today were already evident by the middle of the eighteenth century. While eastern parts of the colony looked to Boston, western parts of the colony found New York best equipped to serve their commercial and cultural needs. There were, furthermore, within Connecticut itself a number of growing urban centers, both on the coast and inland, including Middletown, New Haven, New London, Norwich, and Wallingford. Here as elsewhere in New England by the middle of the eighteenth century both group settlements and single dispersed farms were widespread. Though commerce was important, here again more people were concerned with raising crops and livestock.

Within the small area of Rhode Island there was a considerable amount of diversity. The flourishing town of Newport was both a cultural and commercial center, producing, among other things, nails, rum, sugar, candles, and ships. Foreign trade with many ports on both sides of the Atlantic, in the Boston pattern, was important. While there were many small farms in Rhode Island, there was also a group of “gentlemen farmers,” with substantial holdings of both land and slaves. It was these latter, the Narragansett planters, who were making of the Narragansett country a specialized commercial agricultural area; they produced milk, cheese, butter, pork, beef, and livestock for sale, and based the agricultural economy upon the use of hay and pasture land.

MIDDLE COLONIES

While the New England colonies had a total population of about 360,000, the Middle colonies, comprising New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, had about one-fifth fewer (296,000), or somewhat less than a third of the total population of all the mainland colonies. In some ways the Middle colonies were unlike both New England and the colonies to the south. Whereas settlement in New England initially was on a community basis, in compact groups, in the Middle colonies single farmsteads were a more common form of settlement; and the single units of settlement in the Southern colonies were often large, cultivated through the use of slave labor, whereas in the Middle colonies the individual family farm predominated, and was cultivated and run by the family who owned and resided on the farm. One aspect of the regional distinctiveness of the four Middle colonies is implicit in the alternative name bestowed upon them by contemporaries: they were called “Bread colonies” because their inhabitants produced and sold large quantities of Indian corn, wheat, flour, and breadstuffs.

In New York, the settled area in 1750 was still largely restricted to the Hudson Valley and the small islands at the mouth of the river, although settlers were beginning to move into the Mohawk Valley. The British government continued the early Dutch practice of granting large estates, so that by 1750 large amounts of land were concentrated in the hands of a small number of people. This practice reduced the appeal of the area for incoming settlers and the colony gained relatively few of the many arriving from overseas. The large estates along and to the east of the Hudson were farmed if at all on a tenant basis, or through the use of slave, indentured, or hired labor. The existence of such manorial domains, often equipped with the barns, mills, granaries, outhouses, and other features associated with large-scale production, gave New York something in common with sections of the Southern colonies. The decline in the fur trade and the emphasis on a staple crop for export accentuated the similarity.

At one end of one of the small islands at the mouth of the Hudson River was the metropolis of New York. It functioned not only as the commercial, political, and social center of the province, but also as the trading center for parts of eastern New Jersey and western Connecticut. Although the city was still not as populous as Philadelphia, and possibly not even as large as Boston, the inhabitants formed an important center of consumption. Captain Tibout, for example, was a farmer on the outskirts of New York; in 1757, he obtained three-quarters of his farm income from the sale of cabbages, turnips, and other “Garden truck” to New Yorkers, and manured his land with the mud, dirt, and dung that he carted back from New York each day.3

Pennsylvania was the most popular destination for eighteenth-century immigrants. The province reaped the fruits of William Penn’s early publicity campaign in Europe, and among the many first setting foot in America on Pennsylvania soil Germans and Ulster Scotch-Irish were particularly well-represented. In 1750, for example, over four thousand Germans landed in Philadelphia, and the German influx was at its peak between 1749 and 1754.4

Not all of the immigrants stayed in Pennsylvania. Some of the Scotch-Irish and Germans only stayed long enough to work off their indentures or to earn a little capital before moving south to less crowded areas where land was cheap and easier to obtain. Less than ten years after their arrival in the early 1740’s, the Moravians sent some of their members to North Carolina, there to begin again the laborious work of planned pioneering. But enough of the new arrivals stayed in the colony to make it the most populous of the Middle colonies and to set their distinctive imprint upon it.

One of the first views of America that many of the new arrivals saw was the port city of Philadelphia. From the deck of the ship on which they arrived, exhausted immigrants probably saw little more than the wharves of the city and the crowds gathered there, either to greet them or else to carry them off to servitude of one kind or another. But there was much more to Philadelphia than the port facilities. With a population of about seventeen thousand in 1750, it was the largest city in the colonies, a leading cultural metropolis, and an important retail and wholesale trading center. The large urban population constituted a market for some of the farm produce of the interior and an outlet for shipment of the rest to other colonies or to ports across the Atlantic. The growth and size of the city was reflected in the use of land immediately outside it; so much of the forest in the vicinity of the city was cut, that there was already a shortage of wood in the area, and the land around Philadelphia was of such value that it was cultivated more intensively than elsewhere.5

The growth of Philadelphia was partly a consequence of the agricultural productivity of the colony. A usable road network within the province enabled wagons to transport a variety of farm products to the city. One writer ventured an estimate of the volume of this overland trade: “There may be from 7000 to 8000 Dutch Waggons with four Horses each, that from Time to Time bring their Produce and Traffick to Philadelphia, from 10 to 100 Miles Distance.”6 Wheat, flour, bread, Indian corn, beef, and pork were all exported in considerable amounts; agricultural products such as these furnished the basis of the export trade carried on by the five hundred ships annually entering and clearing the port of Philadelphia in the 1750’s.7 Nonagricultural exports included skins and furs, ships and wood products, as well as much of the iron produced by ironmasters in the province.

Western New Jersey and the Delaware counties felt the effects of their proximity to the large collecting and distributing center of Philadelphia. Most of the settlers of the Jerseys, which by midcentury had a population of about 65,000, were so located that they had easy access to either New York or Philadelphia, whence they exported surplus amounts of grain, beef, pork, and forest products to the West Indies and Europe. The alteration of some of the forest land was so effective that by this time much of the white cedar had disappeared from the southeastern swamp lands.8

Confusion concerning titles to land plagued officialdom in the Jersey’s. This was partly because the two proprietary groups retained interest in land even after New Jersey became a royal province, and partly because of the existence of disputed territory in the area adjoining New York. But disputes about land titles did not prevent squatters from moving onto lands in real or feigned ignorance of legal niceties.

On the other side of Delaware Bay from New Jersey were the three counties that constituted the sum total of the colony of Delaware. The area was small, the population was less than thirty thousand, and the colony was chiefly remarkable for its anomalous political status. A traveler who passed through its capital, Newcastle, wrote of the town in slighting terms: “It is … a place of very little consideration; there are scarcely more than a hundred houses in it, and no public buildings that deserve to be taken notice of. The church, presbyterian and quaker’s meeting-houses, court-house, and market-house, are almost equally bad, and undeserving of attention.”9 But Newcastle did have some of the essential attributes of an urban settlement and was also probably of some importance as a port of disembarkation for many of the immigrants to the colonies.

SOUTHERN COLONIES

Adjacent to the Middle colonies was Maryland. Sometimes assigned to them, at other times referred to as one of the Southern colonies, in reality mid-eighteenth-century Maryland fits neither category very well. It is perhaps more appropriately regarded as a transitional area. In the predominance of white rather than Negro labor, in the importance of bar iron and pig iron production, in the increasing emphasis upon wheat, in the variety of crops produced, in the growth of a port city flourishing on the basis of an increasingly widespread use of wagons for carriage to and from the interior—in all these respects conditions in Maryland resembled those in Pennsylvania. The changes that were going on in the early 1740’s caught the eye of one traveler, who remarked upon a development in Maryland that was accentuating its similarity to the Middle colonies: “The Planters in Maryland have been so used by the Merchants, and so great a Property has been made of them in their Tobacco Contracts, that a new Face seems to be overspreading the Country; and, like their more Northern Neighbours, they in great Numbers have turned themselves to the raising of Grain and live Stock of which they now begin to send great Quantities to the West Indies.”10 Tobacco, however, continued to play an important role as an export staple in Maryland, and this with the large number of tidewater plantations and the presence of a political aristocracy were features more characteristic of Maryland’s southern neighbors.

There were about 140,000 people in Maryland in 1750 and urban settlements played an important role in the colony. Frederick, Georgetown, and Hagerstown were incorporated about this time. The increased use of overland trade and transportation bolstered their growth, for they were essentially trading centers. Their beginnings were modest, but their population and size, and the range of services they offered, multiplied rapidly; by 1771, Frederick was said to offer “all conveniences, and many superfluities” and was an important link in trade between the interior and Baltimore.11 The rise of Baltimore was spectacular. The boom that began in the 1740’s was a consequence of the increasing density of settlement in the western and northern parts of Maryland, the greater use of road transportation, and the export trade in farm crops, particularly wheat. In its commercial importance Baltimore soon overshadowed Annapolis, although the latter continued to serve as the cultural and political center of the colony. The inhabitants of Annapolis lived in what was one of the most remarkable of all colonial centers. Builders of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have not entirely submerged its distinctive layout and distinguished architecture.

The Potomac River was the southern boundary of Maryland and beyond this river were the Southern colonies proper, comprising Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Despite differences in area, population, and length of settlement, they all exhibited certain similarities. They contained about 375,000 people, or roughly a third of the total population of the mainland colonies, and Negroes made up a considerable proportion of the population in all of them. There was in each of the Southern colonies a segment of society that constituted something approach...