![]()

Chapter 1

On Shaky Ground

Early in the evening on Friday, March 10, 1933, ten-year-old Ruth Ashton was sitting by her radio in her Compton home listening to one of her favorite serials when the ground began to shake.1 Windows shattered, doors collapsed, and stores “burst open.” Brick chimneys were “snapped off,” roofs “caved in,” and walls “buckled,” as people ran for safety from their homes and businesses.2 The brutal earthquake rattled California’s southland for thirteen long seconds. Though the epicenter lay off Newport Beach’s shore, Southern Californians from Ventura to San Diego felt the initial tremor. At 6.3 on the Richter scale, seismologists did not consider it a major shock. Residents felt otherwise. The quake left 118 people dead and caused more than $40 million in property damage over a twenty-mile radius.3

According to engineers who surveyed the area, the earthquake hit hardest in Compton, then a small residential community of just over four-and-a-half square miles that housed fewer than fifteen thousand people, the vast majority of whom were white and working class. The earthquake “either razed or severely damaged” almost all of Compton’s three thousand stores, offices, and residences. Long Beach, a port city just south of Compton, suffered the greatest loss of life and greatest total damage, but Compton suffered the greatest proportionate damage.4 Compton’s police station and city hall lay in ruins. Fearful for the integrity of the remaining buildings, many residents refused to reenter their homes, opting instead to pitch tents or move furniture into vacant lots where they cooked over open fires. Amid the chaos, sailors, marines, police officers, deputy sheriffs, and American Legion members guarded the town to keep the peace.5 Yet all of this assistance did not translate into a quick recovery. Even when most students in Los Angeles County returned to school, Compton was one of three locales with unsafe educational facilities. The quake had shattered their town.6

The earthquake was a tremendous setback for Compton, but it alone did not put the town and its schools on shaky ground. In addition to external factors such as the quake, the way Comptonites were developing their town would have ramifications down the line. From early on, Compton’s residents valued local control over drawing boundaries and residential growth, and they resisted building industry. As a result, by the time of the earthquake, the town already had a tenuous infrastructure. Compton was a working-class bedroom community with a low tax base, and Compton schools thus had precious little financial safety net. Once the quake hit, the suburb did not have the resources to rebuild and accrued deep debts that would plague the town and its schools for decades to come.

In its formative years Compton faced in quick succession two major crises: an economic depression and a natural catastrophe. Both of these strained Compton’s meager tax base, resulting in an ill-supported infrastructure. When confronting these combined pressures, services—such as schooling—suffered. The demographic, political, and economic changes created uneasy footing on which Comptonites navigated their educational opportunities.

Life Before the Quake

Compton began as a small farming town. On December 6, 1866, Francis Temple and Fielding Gibson purchased a portion of the Rancho San Pedro from Spanish colonizers.7 Less than a year later, a small band of approximately thirty disappointed gold seekers from the San Joaquin Valley, led by Griffith D. Compton and William Morton, established Compton on this land, making it the second oldest “American” community in the area. These Anglo-American settlers were Methodists, who sought arable farmland and a permanent home where they could maintain their traditions and mores. Founded by devout people, Compton retained its religious tone, even after other denominations moved in.8

Compton soon became known for its farms. An 1887 Los Angeles Times article included the town in its report on “prosperous agricultural settlements,” and described its bounty of corn, pumpkins, and alfalfa.9 In 1893 local farmer Amos Eddy sent seven cuttings of alfalfa to be placed on exhibit at the 1893 Chicago’s World Fair. The height of the crop was so astonishing that Eddy included a sworn affidavit, in order to curb any doubts of its authenticity.10 Agricultural successes like Eddy’s and affordable land drew people to Compton. Savannah Chalifoux’s father moved to the town in 1906 because he was able to buy a farm. His family had recently moved to California from Illinois, after spending some time in St. Louis and Nebraska. Compton fulfilled his dream of owning land. Though the land was “a bad piece of property” for farming, it supported sugar beets, and the family could make a living.11

Compton residents also raised poultry and hogs and produced dairy products. By the end of the nineteenth century, Compton had the largest cheese factory in Southern California, and, due to the town’s proximity to multiple markets, its cheese and butter gained “a wide reputation.”12 A 1909 travel article encouraged tourists in Los Angeles to visit Pasadena, “a thriving business city and health resort”; Santa Monica, “a popular seaside resort”; and Compton, “the center of the dairy district.”13 Agriculture and the tourist industry played the leading roles in Los Angeles County’s early economy, and while each town had its strengths, Santa Monica’s and Pasadena’s proved more resilient as the region evolved into a more urbanized area.14

Settlers in Los Angeles County established independent communities. At first, most were loosely knit agricultural settlements, with the exception of the tourist attractions and harbor communities.15 Compton and Pasadena were two of the earliest, and a comparison of the two offers insight into Compton’s development.16 Built in the same era, Compton diverged from Pasadena in significant ways, not the least of which was that, unlike Pasadena, Compton did not attract regular outside visitors. While Pasadena’s founders immediately set out orange and lemon groves, they also turned the town into a resort community. Pasadena became a favorite place for land speculation, and as a result its population mushroomed during the Southern California land boom of 1886–88.17 The rapid influx of new residents settled into a comfortable stream by 1890. Pasadena’s boosters continued to take advantage of both the town’s stop on the railroad and its isolation from city life, attracting winter visitors with hotels, shops, attractions, and restaurants. Hoteliers built inns and boarding houses, as well as grand hotels in the 1890s, bringing in wealthy patrons. The grand hotels thrived in the warm winter months, serving both overnight guests and locals who sought a night out at a concert, ball, or a multitude of other high society gatherings. Indeed, many of the seasonal residents were millionaires, who spent their time in mansions they had built on and off Orange Grove Avenue.18 By the 1920s, Pasadena had the wealthiest per capita population in the country because of this concentration of extreme wealth.19 The majority of the residents, though, were unable to afford these mansions and instead resided in quintessential Southern California bungalow homes. Pasadena’s incorporation of different classes set it apart from towns like Compton, which never had a wealthy tax base. From these foundations, Compton and Pasadena would take dramatically different directions in their development.

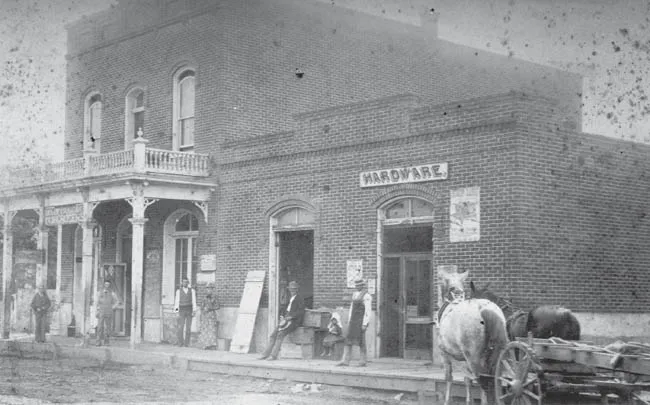

Though Compton did not attract the same number of tourists as Pasadena, a small business district did exist to serve the immediate community. In 1887, Compton’s establishments included a “fair-sized” hotel, two drug stores, two dry goods and grocery stores, one “fancy” grocery, and a jewelry shop. The town also supported hardware, harness, wagon, and blacksmith shops.20 The business district remained minimally developed, however, because it served as a destination for locals only. At the turn of the century, Compton’s population remained small, making it unnecessary to expand the downtown area.21

Figure 6. In 1887, Compton had a block for businesses, including hardware and grocery stores. Courtesy Archives & Special Collections, California State University, Dominguez Hills.

Compton’s location could have helped make it a business hub, but instead it became an affordable place to live for those who worked elsewhere. The small town bordered Los Angeles and Long Beach, the two largest cities in Los Angeles County, and because of their proximity Comptonites did not depend solely on the local economy for their livelihoods. The Southern Pacific Railroad gave Compton residents easy access to both cities, while two major truck highways, Alameda Avenue and Long Beach Boulevard, traversed Compton as they linked downtown Los Angeles with the ports. Compton’s proximity to these modes of transportations made it geographically desirable for working-class residents.22

Many Compton residents worked in Los Angeles or Long Beach. Beginning in the last part of the nineteenth century, both cities had grown rapidly. In 1880, with a population of only 11,000 residents, Los Angeles did not rank as one of the top hundred most populous places in the country. By 1920, however, it had risen to tenth among the country’s urban places, the largest city in California with a population of over 575,000. Just ten years later, the City of Angels had over 1.2 million residents, and the population continued to rise as did the city’s physical size. Through a series of annexations the city grew by approximately 80 square miles. The county population rose from just over 900,000 in 1920 to over 2.2 million in 1930, an average of 350 newcomers a day for ten years.23 Los Angeles had gone from a rural outpost to the West’s leading financial, entertainment, and industrial center.24

Long Beach also transformed during this period. Founded as a seaside resort in 1881, the town came to attract vacationers from across the United States. Among Southern California beach towns, Long Beach came to have it all: a municipal auditorium to host gatherings; upscale and affordable hotels; and a streetcar to transport visitors to the rest of the Los Angeles area.25 The city’s wealth boomed with the discovery of oil, first in 1910 and then with the famous 1921 Signal Hill strike. With oil came increases in real estate prices and land speculation. Like neighboring Los Angeles, the city grew in population and size, as it annexed adjoining land. The business district expanded and the city became more urbanized, with paved streets and large buildings.26

Unlike Long Beach and Los Angeles, Compton was built as a rural town and had little civic infrastructure. Little changed even when, in May 1888, Compton became the seventh town in Los Angeles County to incorporate. This incorporation developed as a response to the Los Angeles region’s real estate boom in the 1880s; Compton residents looked to manage their community and keep its identity in the face of regional change. Incorporation gave residents some measure of power over development and taxes. Residents incorporated the town as a sixth class city, meaning it could elect a mayor and raise municipal revenues, because they wanted “a more efficient government” and believed the county was providing “inadequate control.”27 Residents wanted internal improvements, better police and fire protection, and limits to itinerant peddlers and outside merchants. Desires did not always match reality, however. The town’s central district began the new century without paved streets or public utilities. It also lacked a city hall and fire and police stations.28

Most Comptonites were white, and Compton workers wished to define who worked in their town on racial and ethnic lines, but the town’s government failed to tackle this issue. In 1893, eleven years after the enactment of the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred the entrance of Chinese workers to the United States, the issue of nonwhite workers in Compton came to a head, culminating with “an incipient riot.”29 In this case, white locals demanded a rancher dismiss his thirty Chinese employees. When the rancher refused to “discharge the heathens,” the whites threatened violence.30

Racial violence targeted against Chinese workers affected other places as well. Most notably, an anti-Chinese riot rocked Los Angeles in October 1871, twelve years before the uprising in Compton. Another such example was in Pasadena. Though a majority white town, Pasadena was also home to small populations of Latino, Japanese, Chinese, and black ...