![]()

CHAPTER 1

Financial Pain

No one is beyond the pale of human existence, provided he pays for his guilt.

—Karl Jaspers

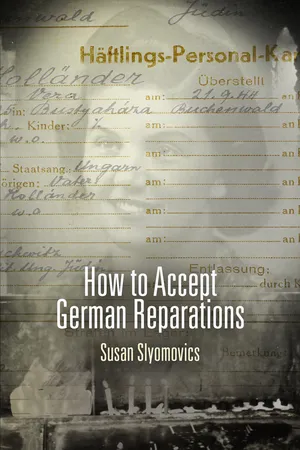

My particular family history illuminates justifications for and against reparations through discussions of indemnification, the anthropology of “blood money,” guilt, and responsibility embedded in the ways these approaches both do and do not shed light on my mother’s refusal to accept reparations for Auschwitz, in contrast to my maternal grandmother’s implacable pursuit of reparations from Germany, Hungary, and the Ukraine for over four decades until her death in Israel in 1999 (Figure 2). My research project investigates aspects of histories and legal instruments of international human rights law relevant to remedies and specifically to a historical moment during which my family and their larger surrounding Jewish community after World War II were forced to confront the perils and possibilities of redress.

Why do people pursue reparations? The effect of financial indemnities as the primary form of reparation to survivors of torture and disappearance and the pursuit, or refusal, of reparation are part of a growing literature in human rights legal studies, with Holocaust survivors an obvious, much-studied group. When human rights violations are presented primarily through material terms for indemnification, acknowledging an indemnity claim becomes one way for victims to be recognized. Remedy and redress are processes that not only afford a vindication to the injured but also assume, or perhaps create, the existence of legal instruments with practical outcomes that determine what is to be done and how to rectify wrongs. When a government commits wrongs against a group, money emerges as the potent remedy to restore justice. In all its varied meanings and typologies, the term “reparations” is currently the preeminent remedy,1 owing much to the unprecedented legal history of the Nuremberg Trials prosecuting the Nazi leadership and to German redress programs for victims of Nazi persecution in the aftermath of World War II. The most recent example to draw on these German precedents is the United Nations guideline on remedy and reparation, dated April 2005 and worth quoting fully:

Figure 2. My mother and grandmother in Prague, 1946, one year after their liberation. Author’s collection.

Restitution refers to actions that seek to restore the victim to the original situation before the gross violations of international human rights law or serious violations of international humanitarian law occurred. Restitution includes restoration of liberty, enjoyment of human rights, identity, family life and citizenship, return to one’s place of residence, restoration of employment and return of property. Compensation refers to economic payment for any assessable damage resulting from violations of human rights and humanitarian law. This includes physical and mental harm, and the related material and moral damages. Rehabilitation includes legal, medical, psychological, and social services and care. Satisfaction includes almost every other form of reparation including measures that halt continuing violations, verification of facts and full and public disclosure of the truth in rights protective ways, the search for the missing, identification of bodies, and assistance in recovery, identification and reburial in culturally appropriate ways. Satisfaction also includes official declarations or judicial decisions that restore the dignity, reputation, and legal rights of the victim and persons connected with the victim, public apology and acceptance of responsibility, judicial sanctions against responsible parties, commemorations and tributes to the victims. Guarantees of non-repetition include measures that contribute to prevention, ensure effective control over the military and security forces, ensure proceedings occur with due process, fairness and impartiality, strengthen the independent judiciary, protect human rights defenders, prompt the observance of codes of conduct and ethical norms, including international standards, by public servants, promote mechanisms for preventing and monitoring social conflicts and their resolution; review and reform laws contributing to or allowing the gross violation of international human rights laws.2

In sum, the reach of reparations as a remedy encompasses restitution, compensation or indemnity, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of nonrepetition.

An early post-World War II German remedy, a legal measure imposed in 1947 during the Allied Occupation of Germany, was the restitution (Rückerstattung) of Jewish properties that the Nazis stole, confiscated, or, according to their racial terminology, “Aryanized.”3 But how to deal with heirless personal and communal property once owned by eradicated Jewish communities? The eventual fate of material goods and assets belonging to a destroyed European Jewry presented complex problems. Because a defeated Germany was the cause of the disappearance and death of Jewish owners, the impetus to formulate laws and administrative practices arose from a fear that any disposition of assets might revert, as was customary, to the benefit of the state, namely, Germany, in this case the acknowledged perpetrator. Assets estimated at $14 billion would otherwise go to enrich Germany. In addition, historian Ronald Zweig summarizes the dilemma of postwar Jewry facing the daunting tasks, both moral and organizational, of how to press claims: “How could Jews negotiate with Germans so soon after the crematoria and the gas chambers of Hitler’s Third Reich? What recompense was possible for the murder of six million people and the destruction of communities hundreds of years old? How was it possible to estimate the value of individual and communal Jewish material assets, which the Germans had plundered between 1933 and 1945?”4 The postwar Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), nonetheless, took responsibility for meeting material claims by Jews in a widely publicized speech by Chancellor Conrad Adenauer addressed to the German parliament on September 27, 1951:

Unspeakable crimes have been committed in the name of the German people calling for moral and material indemnity, both with regard to the individual harm done to Jews and to the Jewish property for which no legitimate individual claimants still exist. . . . The Federal government is prepared, jointly with representatives of Jewry and the State of Israel, which has admitted so many stateless Jewish fugitives, to bring about a solution of the material indemnity problem, thus easing the way to the spiritual settlement of infinite suffering.5

A year later, September 10, 1952, the Federal Republic of Germany signed Protocol No. 1 “to enact laws that would compensate Jewish victims of Nazi persecution directly” and Protocol No. 2 that would “provide funds for the relief, rehabilitation and resettlement of Jewish victims of Nazi persecution,” laws both confirmed and partially extended on the unification of East and West Germany in 1990.6 Policies enacted were based on sincere government apologies and the principles of restitution, indemnification, and reparations: restitution as the restoration of actual individual assets, indemnification as compensatory payments, and reparations in the form of collective payments made by one state to another, in this case to the Jewish people and eventually to the State of Israel after its establishment in 1948.

German reparations are called Wiedergutmachung—literally, “making good again.” Germany has created the largest sustained redress program, amounting to more than $60 billion in payments, a landmark process that set into motion a global legal transformation in how abuses by a state may be evaluated. In contrast to this German model, the absence of governmental atonement and apology is assumed to signal that a more common legal category is operating, one in which parties agree to a settlement: one side pays without acknowledging or apologizing for violating any laws, and the other side, the aggrieved party, receives a cash award; no liability is implied or assumed.7 Therefore, ways to gauge the worth of reparations in the case of Germany were based on a government that admitted to harm committed in the name of Germany and that sought to atone for past injustices, in part by paying victims money.

Money and Suffering

Money is looked upon as an impersonal, colorless social abstraction, according to Georg Simmel in his foundational 1878 treatise on The Philosophy of Money:

Money is the purest reification of means, a concrete instrument which is absolutely identical with its abstract concept; it is a pure instrument. The tremendous importance for understanding the basic motives of life lies in the fact that money embodies and sublimates the practical relation of man to the objects of his will, his power and his impotence; one might say, paradoxically, that man is an indirect human being. I am here concerned with the relation of money to the totality of human life only insofar as it illuminates our immediate problem, which is to comprehend the nature of money through the external and internal relationships that find their expression, their means or their effects in money.8

Exemplifying Simmel’s notions about money’s abstract, neutral, and rational qualities is the use of cash payments between individuals and collectivities to atone for murder, torture, and disappearance. Although Simmel described the frequency of compensatory money payments before the twentieth century, since World War II, a plethora of mechanisms has emerged most prominently to promote the concept that a life damaged or lost as a consequence of violence can be paid for. This chapter draws on aspects noted in Simmel’s survey of the complex properties of money payback, especially the ways in which he was forcefully struck by the “intensity with which the relationship between human value and money value dominates legal conceptions.”9 Buttressed by numerous cross-cultural examples from the anthropological literature, Simmel concluded in relation to an omnipresent “intensity” that offenders who pay money to resolve murder cases constitute a clear and public admission of guilt to the surrounding society.

Some conclusions based on Simmel’s key insights are, first, that an admission of guilt accompanied by cash underpins the historical basis for any legal system of fines and, second, that such a system evolves effectively into mechanisms with which to buy social peace and avoid endless retribution and feuding.10 Systems of fines and payments—grouped by sociologist Viviana Zelizer under the rubric of “the monetization of guilt”—in turn produce varied and unintended consequences. An objective monetary value may be attached to human beings, just as Simmel taught, but also dynamically and reciprocally, money involved in such an exchange becomes endowed with social significance. What are new meanings attached to special purpose money payments?11 Especially following the work of scholars Daniel Levy and Natan Sznaider and expanding on Simmel’s insights, how are we to understand the politically charged realm of financial reparations disbursed not by individuals but instead emanating from the state? What is different when the state bestows funds on recipients who are its current or former citizens? Levy and Sznaider provide some answers:

At the level of states and ethnic collectivities, money is exchanged for forgiveness. Legal and politically consequential forgiveness are distinct from feelings of forgiveness. And at the level of individuals, the act is one of closure. Money symbolizes the irrevocable admission that a crime has been committed. As Marcel Mauss had already stated in 1925 in his analysis of The Gift, symbolic exchanges are relations between people as much or more than they are relations between objects. In the case of restitution, the acceptance of the money symbolizes the acceptance of the giver. And that is an acceptance that would never be possible on the basis of personal relations.12

Drawing on aspects of financial reparations raised by Simmel, Zelizer, Mauss, and Levy and Sznaider, I investigate several related themes throughout this book. (1) How are current reparations related to “blood money”? (2) Can Simmel’s “intensity” be understood in relation to the ways in which money is “sacralized,” that is, made sacred, both by an association with the damaged, tortured or missing body of the citizen and by means of the state’s financial reparation procedures? (3) While the acceptance of money may signal the acceptance of guilt by the giver, does it truly signal any kind of acceptance by a recipient designated the injured party, as Levy and Sznaider suggest? Finally, and what lies at the heart of my inquiry, (4) why are restitution and reparation necessary but never enough, at least not always and not uniformly everywhere? What, if anything, does my intimate knowledge of Holocaust survivors’ sufferings grant me? Beyond the subjective language of daughterly empathy, what should I do as an anthropologist caught up in the contemporary concerns of social scientists who are shifting away from the abstractions of money toward the impact of moral sentiments?

“Blood Money”

Reparations (the plural form routinely used) now mean primarily one thing—money.13 It is not easy to come to grips with the messy realities of those who receive reparations—a group variously called victims, survivors, persecutees, claimants, deponents, litigants, heirs, my extended family, my mother and grandmother. Is the principal problem a central incompatible relationship that posits a link, a direct exchange between money and suffering? Rational choice economic theories that once privileged homo economicus, a self-interested money-maximizing “economic human,” offer little clarity because the intensity of victim emotions plays a salient role. While many victims choose not to speak, and even those who do speak do not speak with one voice, they do pronounce a strikingly consistent reaction to money. Irrespective of an individual’s decision to claim or reject reparation funds, most describe participation in monetary remedies as the calculating, materialist, instrumental monetization of their sufferings. Money received through reparations is, therefore, “morally earmarked,” following sociologist Viviana Zelizer’s descriptor for the social life of money: “In everyday existence, people understand that money is not really fungible, that despite the anonymity of dollar bills, not all dollars are equal or interchangeable.”14 In many historic and legal cases, financial reparations have been morally earmarked as “dirty” sullied money and labeled in diverse cross-cultural settings “blood money.”

Anthropological theories have long posited a progressive evolutionary model from “blood money” to reparations according to which feuding communities without compensation mechanisms evolve into advanced societies with blood money payments that exclude the retaliatory lex talionis, an eye for an eye. The centuries long use of a form of quantifiable scale, either money or goods, to substitute for a life as blood debts also points to the monetization of interpersonal relations in early societies long before our capitalist, state-backed deployment of moneys. A final stage of sociocultural sophistication occurs when, for example, a suprajuridical body is established, such as the tribal assembly or a court to adjudicate damages and specify blood money in cases of death, rape, and violent disputes.15 Thus, for victims to refuse financial compensation precisely because it is “blood money” is to remain mired in the primitive stages of perpetual feuding, revenge, bitterness, and savagery.16

Nonetheless, many refuse. Some fifty years after Germany’s postwar indemnities, recipient responses pronounce the same epithet. “Blood money” has reappeared in widely disparate cases based on financial reparations, whether the atrocity indemnified is ethnic cleansing, genocide, or a state’s ideological war against its own citizens. My mother refused the postwar German Wiedergutmachung compensation program because, she informed me, it was “blood money”: nothing could compensate for her father’s murder in Austria’s Mauthausen Camp. Refusing money had once been her cleansing process:

I didn’t betray my father’s memory by taking money from the killers. Since I started receiving monthly reparation checks in 2004 [for slave labor], they have become a constant reminder of my father’s murder. They prevent healing and building a new life in a new country. Before I was clean, I took nothing. (Vera Slyomovics, interview by author, Vancouver, Canada, June 1, 2007)

Many concentration camp survivors who refused compensation reputedly reasoned, “If I don’t get the money, the Germans will feel more guilty.”17 So, too, the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, the organization of families of those disappeared during Argentina’s “Dirty War,” divided rancorously in 1986. The president of one splinter group, Hebe de Bonafini, rejected exhumations of cadavers (“we will not be contented by a bag of bones”) and government indemnification (“blood money”).18 Similar reactions were voiced in Algeria as a result of disappearances occasioned by the country’s brutal internal war of the 1990s. The head of the Algerian Mothers of Disappeared Children, Nacéra Dutour, disdainfully rejected the extensive 2005 Algerian financial reparations protocols by refusing to file for reparations for her son, Amine Amrouche, forcibly disappeared in 1997. Subsequently, Dutour told me that Algerian reparations were “tribal,” as if the Algerian regime could force a retrogade return to some imagined prelapsarian tribal collectivity that subsumes each victim’s experience on behalf of the public good (interview with Nacéra Dutour, Paris, November 22, 2003). Like my mother, Dutour exemplifies the rights-bearing citizen motivated by her own conscience and unwilling to take into account the persuasiveness of moral imperatives emanating from sources of authority such as the state.19

Cash awards to the living on behalf of the dead are so deeply enmeshed with the repugnant notion of blood money that all those associated with claims processes, even outsiders such as lawyers and administrators, are morally implicated as if by contagion. Kenneth Feinberg, the American lawyer charged by the George Bush administration as the...