![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Women and Silk

Remapping the Silk Routes from China to France

I BEGIN WITH two stories of women “working” silk: two accounts of female protagonists poised at either end of a long chronological spectrum and a wide geographic expanse that stretches from seventh-century China to twelfth-century France. These culturally diverse fictive women are joined across time, place, and social class by complex threads of silk that connect those who wear and display this costly fabric with those who make and decorate it. The first story is a popular Chinese legend concerning the Silk Princess, a woman who is held responsible, along with her two female attendants, for smuggling the invaluable knowledge of sericulture and silk weaving out of China and into the west.1 The second account, a curious passage in a medieval French romance called Le Chevalier au lion (Yvain), describes three hundred captive women silk workers who transport their knowledge of lucrative silk weaving from the mythic “Isle of Maidens” into the fictive landscape of Arthurian romance.2

Both tales chronicle displaced women and cultural border crossings. Both feature female protagonists as knowledgeable carriers of key technological innovations that can potentially generate significant economic wealth. And yet the skilled women silk workers depicted in the Chinese legend are servants and those in the Arthurian romance outright captives. All are foreign women transported against their will. While the Silk Princess travels to a neighboring country as part of a political marriage alliance, the Chinese silk weavers who accompany her are transferred to ensure the continued production of elegant attire for their mistress. The female silk weavers in the French tale are destined similarly to make lavish cloth for elite members of the courtly household where they are held captive. Silk figures in both accounts as a commodity that travels in tandem with the displacement of women who are skilled at producing it.

As a scholar of medieval French literature and culture, I began this project with the story of captive silk workers in Chrétien de Troyes’s Yvain and came to the Chinese tale of the Silk Princess by reading backward from twelfth-century France to seventh-century China and, simultaneously, by following the historical Silk Road in reverse. My investigation of the abundant references to silk in Old French literature quickly drew me into new intellectual terrain: across the borders of the Arthurian realm and far beyond the frontiers of medieval France, through an extended geography that crosses the Mediterranean to the Levantine coast and continues into Persia, Central Asia, and China, while also traversing the Pyrenees into Spain and North Africa and continuing on to Egypt.3 It is in this expanded and expansive geography, I discovered, that a gendered story of silk production unfolds, a story of silk cultivation and manufacture, distribution, and consumption that is largely occluded in the familiar account of the Silk Road. For most readers, the network of trade routes known collectively as the Silk Road calls to mind an image of lucrative commerce: a story of commercial travel between imperial China and its neighboring provinces, extending west eventually as far as the Mediterranean. It is also, in many historical accounts and in the popular imagination, a story largely without female participants.

Women and Silk

By contrast, women figure as central players in the two stories of silk workers that provide the framework for this chapter. Tellingly, the skilled women represented as smuggling silk in the Chinese legend of the Silk Princess are not cast as silk traders or merchants. Neither do the young women silk workers transferred into King Arthur’s realm in the medieval tale of Yvain some five hundred years later actively exchange silk for profit. Rather, all these fictive women are responsible for transporting across cultural borders the highly specialized skill needed to produce silk itself. Indeed, these mythically inflected accounts of women “working” silk add an important component to the more familiar story of the “Silk Road” as a venue of commercial trade. In fact, the Chinese tale of the Silk Princess and the Old French account of women silk workers offer imagined cartographies of silk making that supplement in important ways the historical accounts of commercial trade routes, whether the initial Asian land routes out of China or later sea routes traversing the Mediterranean. In brief, these stories, and others to be analyzed below, chart cultural iconographies that define the elite classes who wear and use silk in relation to the equally salient issue of the gendered production of silk fabric itself.

Many Silk Roads

The story of silk begins, we are told, in the second century B.C.E., when Zhang Qian and Chinese envoys were sent by the Han emperor Wudi to elicit support of the Central Asian Yuezhi against the invading, nomadic Xiongnu.4 As a result of this foray, diplomatic and economic relations were established and a peace negotiated. The contact then opened a route westward along which a tribute system of exchange developed and flourished under both Han and Tang dynasties (206 B.C.E. to 220 C.E. and 618–907 C.E.).5 What was traded, initially, was silk fiber (raw silk) and silk goods largely in exchange for horses.6

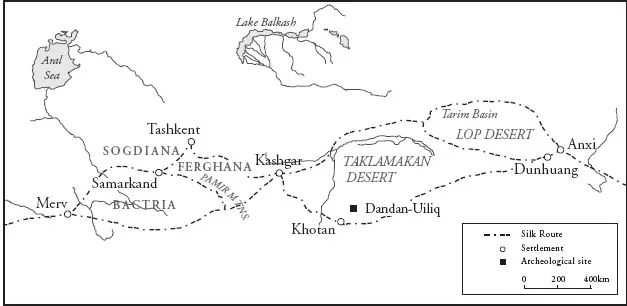

However, silk was not the only commodity exchanged on this route, and goods traded between China and Central Asia did not follow a single path. In fact, the name “Silk Road” was not coined until the late nineteenth century when the Prussian geographer Ferdinand von Richthoven used the term “seidenstrasse” to denote a group of overland routes linking Chang’an (modernday Xi’an) in China to Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan and continuing toward the Caspian Sea and beyond.7 This network of roads facilitated cultural and commercial communications, in some ways not unlike the network of pilgrimage routes that carried medieval merchants, pilgrims, and travelers across France and Spain toward Santiago de Compostela. As the Asian silk routes developed, caravans departed from Chang’an and followed the Great Wall to the northwest, avoiding the Taklamakan Desert in western China by taking either a southern loop through the ancient city of Khotan (Hotan/Hetian) in the Tarim Basin or a northern loop through Turfan (Turpan).8 Both routes converged at Kashgar, and from there crossed the Pamir Mountains into the Central Asian provinces of Sogdiana in modernday Uzbekistan and Bactria in modern-day Afghanistan (Figure 1).9

Figure 1. Asian silk routes. © E. Jane Burns.

The network of trade routes across Central Asia connected a series of desert oases that became market towns, extending westward from Kashgar to Tashkent, Samarkand, Merv (in Iran), and later to Damascus and Mediterranean coastal cities.10 Few merchants traveled the entire length of these roads, or even the key portion of the route between Chang’an and Samarkand.11 Most moved back and forth over short distances on limited stretches of a given route.12 Although in the second century the Greek geographer Ptolemy had mapped a complex network of overland trails extending from the Caspian Sea east to the Pamir Mountains and Romans had been using silk since the first century B.C.E., they did not travel to China itself, but seem to have met on the western shore of the Caspian Sea, in Mesopotamia and the Caucasus, to trade with merchants who had journeyed to the west end of what would later be known as the “Silk Road.”13

From its earliest use in China and Asia silk functioned not only as a luxury item, as it did subsequently in the west, but also as a currency and a safe investment. Alongside gold, silver, and jewels, silk fiber was used to pay debts and dowries. It served as ransom and as security against loans, as payment for artists or scholars, and as offerings at Buddhist temples.14 Originally a tax, known as the Tribute of Yu, paid by the Chinese people to the state treasury, silk became so plentiful in government coffers by the fifth century that it was distributed as salary to Chinese civil servants.15 Spices, of course, were included in the Asian silk trade, although spices were traded in greatest quantities on the sea route to India, and, by the sixth century at least, the term “spices” referred to a range of commodities exchanged in small amounts. In addition to pepper, cloves, and nutmeg, the category of spices could include ambergris, dyes, mordants, scents, pigments, gums, incense, other medicinal items,16 and, not uncommonly, silk fiber itself. Like spices, raw silk was compact and lightweight, hence easy to transport, and extremely valuable in small quantities. Thus, in addition to exporting silk fabric, China supplied the west with raw silk or silk fiber that traveled along the extended network of overland caravan routes from Central Asia to the Mediterranean, some of it to be worked into cloth in cities such as Antioch and Alexandria.17

As silk moved eventually down the eastern Mediterranean coast and into Egypt, it continued to function as currency, serving, according to Goitein, as the “coin of the realm” in international exchange, especially in the textile hub of Alexandria. During the Fatimid period, he explains, all merchants carried some silk as a replacement for cash. Silk fiber was traded in pounds and ounces, according to a standardized price that remained stable from the 1030s to the 1150s.18 Less valuable was floss silk or waste silk, the outer layers of fiber surrounding the cocoon that cannot be unraveled and reeled, but must be “peeled off” and spun.19 But silk could also stand in for gold. When Muslim silk-producing states such as Almería sent tribute to the Christian kingdoms in northern Spain, sums specified in gold were often paid, in fact, in silk.20 The perception and use of silk as currency persists through the high Middle Ages in France, recorded, for example, in the Dit des Marchéans, where the extensive catalogue of merchants at the Champagne fairs groups silk together with gold and silver available from “marchéans … de soie, et d’or, et d’argent.”21

In addition to fostering the large-scale transfer of silk and spices, Chinese silk routes enabled the movement of intellectuals, artisans, and technicians, while facilitating at the same time the displacement of prisoners taken in war and conquest, captives exchanged as tribute, and slaves.22 If Buddhism came to China along the silk routes in the first century, with the first Chinese Buddhist monk traveling west to Khotan two hundred years later in search of missing Buddhist scriptures to be translated into Chinese,23 so too did slave merchants travel these routes. In fact, the slave trade is one of the few places that women become strikingly visible in the larger story of silk. Documents recording the sale of slaves along the silk routes, for example, include at least one instance in which a slave girl is exchanged specifically for a debt of silk.24

It is important to note at this juncture that the historical silk trade depended on two distinct processes that did not always migrate in tandem. Sericulture involved the raising of mulberry trees and silk worms that fed on their leaves, and produced cocoons that were unwound and reeled into silk thread and fiber. That fiber was subsequently woven into silk cloth. Both silk fiber and finished cloth are often referred to by the single term “silk,” thus conflating what were actually distinct material products. In fact, however, the ability to weave silk fabric most often preceded the highly prized knowledge of sericulture itself. Initially, the technology of sericulture moved along established silk routes out of China, passing first to the Persians in the third century and then to the Byzantines in the sixth century. But the Persians and Byzantines, like the Romans all enjoyed the pleasure of wearing and using silk cloth long before they were able to produce silk thread.25 The raising of silk worms and production of silk thread spread widely with the Muslim expansion across North African cities and across the Mediterranean (eighth to eleventh centuries) to al-Andalus, Sicily, and Cyprus, reaching southern Spain in the eighth century and Sicily in the ninth. Sericulture was not, however, adopted in France, where silkworm cultivation proved unsuccessful in the Middle Ages.26

Significantly, silk’s long-standing reputation as a coveted fabric that falls and moves elegantly in space results from the labor-intensive process of meticulously unwinding a single thread from silkworm cocoons, each one producing an unbroken strand of six hundred to two thousand meters in length. The secrets of this process and other phases of silk production—cultivation of the white mulberry tree (morus alba) on which the silkworms feed, raising the worms (bombyx mori), and finally unwinding the cocoons—were fiercely guarded by the Chinese, as they would be later by the Persians and subsequently the Byzantines.27 But in Chinese history and legend, the secrets of ...