![]()

CHAPTER 1

OSSOMOCOMUCK

In the summer of 1584 Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe, soldiers and sailors both in the service of Sir Walter Ralegh, first reached the Outer Banks of what is today the state of North Carolina. The new land, the home of Wingina and his people, impressed Barlowe. “The soile,” he wrote, “is the most plentifull, sweete, fruitfull, and wholesome of all the world.” The Indians welcomed the English, Barlowe noted. They entertained the explorers “with all love, and kindnes, and with as much bountie, after their manner, as they could possibly devise.” Barlowe “found the people most gentle, loving, and faithfull, void of all guile, and treason, and such as lived after the manner of the golden age.”1

And so it is here, in this New World Eden, where most stories of English colonization begin. History, in this sense, is all too often depicted as commencing with the arrival of the newcomers on American shores. But we are interested in a different story. In order to understand the murder of Wingina and its consequences, we must recognize that the peoples Barlowe and the sailors who accompanied him encountered had long histories of their own on this continent. Wingina’s story begins well before Ralegh’s ocean-weary settlers clambered out of their ships’ boats onto the sands of the Carolina Sounds. It is time for us to establish the setting, and the scene of the crime. In order to understand why a young colonist beheaded Wingina and why this act of violence mattered, we must understand something of the beliefs and values Wingina and his people carried into their encounter with the English newcomers. The Indians of the Carolina Outer Banks, these peoples of rivers, sounds, and sea, did not consider the place they lived a new world, and the English explorers intruded into an environment where Indian rules prevailed.

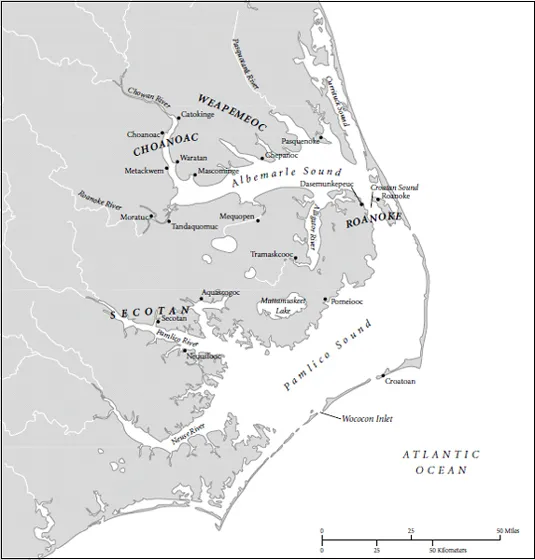

FIGURE 1. Map of Ossomocomuck.

At first, the English thought that the Indians called this new land Wingandacoa. The newcomers placed that name proudly in patents and documents and proclamations once they returned home, until they learned that it did not refer to a place at all. As Sir Walter Ralegh remembered later, “when some of my people asked the name of that Countrie, one of the Salvages answered Wingandacon which is to say, as you weare good clothes, or gay clothes.” The natives’ own name for the region into which these oddly-attired Englishmen had intruded was Ossomocomuck, a term that cannot be translated with certainty, but may mean something as appropriate and simple as the land that we inhabit, the dwelling house, or the house site.2

Ossomocomuck consisted of the coastal region of the North Carolina mainland, from the Virginia boundary south to today’s Bogue Inlet. Its limits to the east included the thin barrier islands of the Outer Banks and a number of larger islands located on the sounds between the two. Roanoke was one of these sheltered islands. It extended westward along a line that ran with the Chowan River south through the present-day locations of Plymouth, Washington, and New Bern.3 The geography of this region shifts constantly. Grasses cover the islands. In places there is soil suitable for agriculture, as well as stands of timber for housing and fuel. Still, wave and wind continually reshape the Carolina Sounds; they always will. Rain in the Carolina interior can swell rivers, and as these waters flow out to sea they deposit sand and sediment that close old inlets between the barrier islands and open new ones. Severe storms, the famous Atlantic hurricanes, only intensify the mutability of the Outer Banks. According to one study, Roanoke Island has seen its northern shoreline recede nearly a quarter of a mile since the late 1500s, and the federal government today devotes significant resources to preserving and maintaining the basic geographic shape of the Carolina Outer Banks. It is and was a world of water, and the relationship of the people who lived there to estuary, sound, and shore played a critical role in shaping their identity. The names of places all bore the mark of their relationship to water: Secotan, the town at the bend of the river; Aquascogoc, the place for disembarking; Weapemeoc, where shelter from the wind is sought; Dasemunkepeuc, where there is an extended land surface separated by water. Roanoke was named for the people who rub, abrade, smooth, or polish by hand, a reference, most likely, to the shell beads produced by the island’s inhabitants.4

Wingina’s people lived in some of the dozens of autonomous Indian communities lining the waters of Ossomocomuck. They were Algonquians, in that they spoke a language and practiced cultural forms related to those of other Indian communities along the Atlantic coast from Maine to the Carolinas. All the Indians in Ossomocomuck spoke closely related languages, a factor that facilitated exchange and interaction between the region’s peoples.5

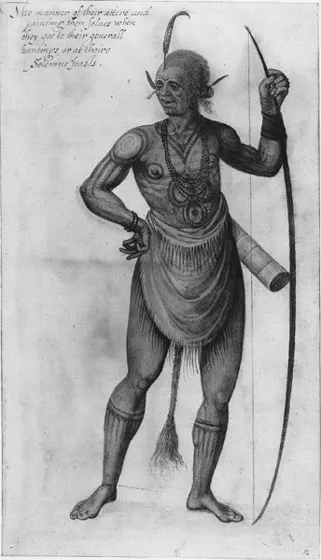

At the time he first encountered the English, Wingina was a man of middle age. Indian leaders on the Carolina Sounds and elsewhere denoted their high status through clothing, body ornamentation, and manner. Some of the neighboring weroances went to elaborate lengths, the English reported. “They cutt the top of their heades from the forehead to the nape of the necke in manner of a cokscombe,” wrote the scientist Thomas Harriot, with a long feather “att the Beginninge of the creste uppon their fore heads, and another short one on bothe seides about the eares.” They wore in their ears “either thicke pearles, or somewhat else, as the clawe of some great birde, as cometh in to their fansye.” Some wore, as well, “a chaine about their necks of pearles or beades of copper, which they most esteeme.” They tattooed their bodies, face, chest, arms, and legs, and painted themselves in patterns of red and silver and white. These images probably represented clan affiliations, and the close relationship in the Algonquian cosmos between human and other-than-human beings.

William Strachey, a secretary for the Virginia Company of London who arrived at Jamestown in 1610, observed a similar practice among the culturally analogous Powhatans of Virginia. These Indians made paint from a root they called “Puccoon,” which they “brayed to poulder mixed with oyle of the walnut, or Beares grease.” Strachey thought that this paint “in Summer doth check the heat, and in winter armes them (in some measure) against the Cold.” This may have been the case, but the painting probably had a ritualistic function as well. Harriot suggested that the individual he described dressed in so elaborate a manner for war, or for “their solemne feastes and banquetts.”6

Wingina’s wives and other elite women dressed up as well. They covered their lower torsos with “skyn mantels, finely drest, shagged and frindged at the skirt, carved or coloured, with some pretty worke or the proportion of beasts, fowle, tortoises, or other such like imagery as shall best please or expresse the fancy of the wearer.” High-status women engaged in elaborate displays of body ornamentation. The women, William Strachey recalled, “have their armes, breasts, thighs, showlders, and faces, cunningly imbroydered with divers workes, for pouncing and searing their skyns with a kind of Instrument (heated in the fire, they figure therein flowers and fruicts of sundry lively kyndes, as also Snakes, Serpents, Efts, etc.,) and this they doe by dropping upon the seared flesh, sundry Colours, which rub’d into the stampe will never be taken away agayne because it will not only be dried into the flesh, but grow therein.” Women wore their hair short in front, long in the back, and gathered up at the back of the neck.7

FIGURE 2. John White, Indian in body paint. White’s caption reads, “The manner of their attire and painting them selves when they goe to their generall huntings or at theire Solemne feasts.”

COURTESY OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

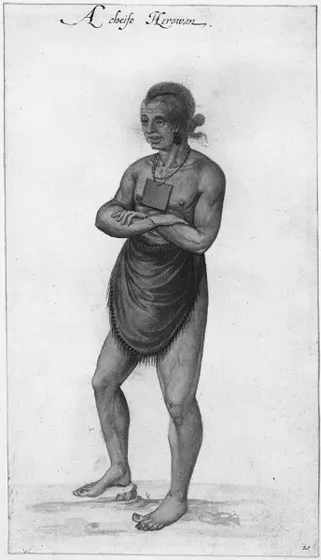

Viewed in the context of these descriptions of the Indians on the Carolina Sounds, the artist John White’s painting of Wingina stands apart. As White depicted him, he was a muscular man, with large eyes and full lips, and appears comparatively unadorned. Perhaps White depicted him without his ceremonial attire. Or perhaps the simplicity of his dress was a matter of style. According to Harriot, Wingina and his advisors cut the hair “like a cokes combe,” with the longer hair in the back gathered at the base of the neck. Wingina and his close advisers also hung stringed pearls and copper beads from their ears, and wore “bracelets on their armes of pearles or small beades of copper or of smooth bone called minsal.” Wingina did not paint or tattoo his body. Rather, he and his advisers “weare a chaine of great pearles, or copper beades or smooth bones abowt their necks, and a plate of copper hinge upon a stringe.” They wore “from the navel unto the midds of their thighs as the women doe . . . a deereskynne handsomely dressed, and fringed.” His manner was grave; leaders like Wingina “fold their armes together as they walke, or as they talke one with another in signe of wisdome.” His followers wore a tattoo on their left shoulder, four vertical arrows, signifying that they were Wingina’s men.8

Wingina spent most of his time at the village of Dasemunkepeuc, on the mainland shore of Roanoke Sound opposite the island, not far from present-day Mann’s Harbor. Here there was access to the great variety of resources in the area, including fertile soil for maize agriculture. Wingina and his people could have moved easily back and forth from Dasemunkepeuc to the village on the northern shore of Roanoke Island. Though its location has not been thoroughly excavated, a consensus exists that the palisaded village of nine houses that Barlowe would visit stood near what is now known as the Dough Farmstead. If so, the village was slightly more than a half-mile from the site of the English fort. The late nineteenth-century archaeologist Talcott Williams found a number of skeletons in a group burial there, and the respected historical archaeologist Jean C. Harrington recovered additional evidence pointing to an Indian town at Dough’s Point. It is unlikely that the island’s thin soil could have supported a large population, and the majority of Wingina’s people must have spent most of their time across the sound on the mainland. Wingina’s followers also interacted closely with Indians from a village farther south on Croatoan Island. Croatoans appear frequently at Dasemunkepeuc, and the evidence suggests that the Indians of Roanoke, Croatoan, and Dasemunkepeuc were unified in some sort of greater community under Wingina’s authority.9

FIGURE 3. John White, Wingina. White’s caption reads “A cheife Herowan.”

COURTESY OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

But what to call this community? I shall use Roanokes in this book, but any name is rife with problems and obscures perhaps as much as it clarifies. We still must ask how these Indians saw themselves. How did they perceive the community or communities to which they belonged? For generations, historians and archaeologists have rather cavalierly identified the Algonquian communities of the Carolina coastal region as belonging to different tribes, but we need not feel bound by these descriptions. Tribe, after all, is an English word, one that native peoples could not possibly have used to describe any part of the reality of their lived experience. This much seems obvious. A look at the surviving evidence from the region suggests that if we are to understand the world in which Wingina lived, and how his head came to be held one day by Edward Nugent, we must look at the level of the village. It was here that Wingina’s people discussed how to react to the newcomers, and how to make sense of the dramatic changes produced by their intrusion into Ossomocomuck. In these villages, the critical events that led to the killing of Wingina took place.

FIGURE 4. Theodor De Bry, “A cheiff Lorde of Roanoac” (detail), engraving from the 1590 edition of Harriot’s Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia.

REPRINTED WITH THE COURTESY OF DOVER PUBLICATIONS.

Archaeologists tell us that human beings have lived in the coastal region of the Carolinas for many thousands of years. The peoples these archaeologists classify as “archaic” lived along the region’s waterways, hunting and gathering, not planting crops. We know little about them. Most scholars believe that they moved into the Carolina Sounds as long as 15,000 years ago, the southern extension of a broader movement of Algonquian peoples into the Chesapeake region and the Carolinas. For what is called the Mount Pleasant phase of the Middle Woodland Period, an archaeological epoch that ran from roughly 300 B.C. to 800 A.D., more abundant evidence is available. Like their ancestors, Mount Pleasant peoples lived by the waterside. They hunted deer, raccoons, rabbits, turkeys, and turtles. They harvested and processed hickory nuts as well. These activities, however, always remained secondary to shellfish collecting and fishing.10

Yet if archaeologists describe the Indians of the region as the descendants of migrants who entered Ossomocomuck many thousand years ago, and debate among themselves how long ago this movement occurred, we must keep in mind that Wingina’s people had their own understanding of their origins. These explanations—these “creation myths”—made as much sense to the Indians who passed them down from one generation to another as did the Book of Genesis to the English. One of Wingina’s followers described his people’s origins to Thomas Harriot. “For mankinde,” Harriot learned, the Indians of Ossomocomuck “say a woman was made first, which by the working of one of their goddes, conceived and brought fourth children.” In this, Harriot wrote, “they say they had their beginning, but how many yeeres or ages have passed since, they say they can make no relation, having no letters nor other such meanes as we to keep recordes of the particularities of time past, but onely tradition from father to sonne.”11

This is all Harriot wrote on the subject, at best a tantalizing glimpse into the worldview of Algonquian peoples who lived in the Carolina Sounds region. Harriot generally sought parallels between his own beliefs and those of the Indians. Perhaps because the Indians’ ideas about their origins rested on premises so different from his own, he said less about them than he did about other subjects. Still, it is possible to move beyond Harriot’s brief description and develop the story more fully. One evening in 1610, for instance, William Strachey sat aboard a boat in the Potomac River, listening to an elderly Patawomeck weroance, Iopassus, describe how the world came to be. Virginia Algonquians, like the Patawomecks, shared many well-documented cultural practices with Wingina’s people. It is at least possible that Wingina and Iopassus agreed at a fundamental level about how the world began.

Iopassus told Strachey that his people “had five gods: four of them were invisible and represented the four winds and the four courners of the earth. The fifth took the form of a Great Hare.” So the dawn of history for the Powhatans began not with a masculine god in man’s image single-handedly creating all of the cosmos, but with a rabbit, a testament to the closeness of the bond between Algonquian human and other-than-human beings. The Great Hare, Strachey learned, “conceaved with himself how to people this great world, and with what kind of Creature...