![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: American Architecture?

Architecture is the best expression of a society, where it is and where it hopes to go.

—Vincent Scully

Buildings spoke to Henry James. When James, a towering figure in the world of American letters, returned to the United States in 1904 after an absence of nearly twenty-five years, he toured his old haunts, the places of his growing-up, and the buildings whispered to him. It is not important here what they said. James’s record of his visit, published as The American Scene, serves as a reminder that buildings, cities, landscapes—the totality of our built environment—speak to all of us.

In this sense, architecture is the one fine art that cannot be escaped. Many Americans go their whole lives without ever reading James, or Edith Wharton or James Baldwin, without ever listening to a symphony orchestra or hearing live jazz. But no one lives a life outside and apart from architecture. Regardless of where we live or what our work might be, we live our lives and do our work within spaces shaped by human imagination and human hands. Architecture thus stands as the one indispensable cultural production.

No less than Egypt, Rome, or the Ottoman Empire, the United States has, since its founding, relied on its buildings and its landscapes to reflect, define, and contest a national identity. Debates over what constitutes an American architecture, and what architecture’s role in the nation’s life should be, have therefore stood at the center of public life. As Americans have wrestled with issues of architectural form and style, with the nature of their cities, and with their relationship to the natural environment, they have evaluated and reevaluated the state of their democratic experiment and the meaning of participation in it by critiquing the design of their homes, their institutions, their urban spaces, and the landscapes that have surrounded them.

We offer here a window onto some of these debates over America’s “built environment.” By that term we mean all the ways in which people shape their surroundings—from formal architecture, to informal, vernacular buildings, to town and city planning, to the design of parks and the manipulation of the natural landscape—and the reasons they have done so. Building the Nation is a critical anthology of American writings about the built environment from the founding of the nation until the close of the twentieth century.

Our approach is to heed the insight of the old Shaker proverb “Every force evolves a form.” Every force in American life—whether the Civil War, the rise of industrial capitalism, the Great Depression or, more locally, the desire of people to live in better homes or of a town to have a public library—has left its mark on the built environment. To the proverb we add, “Every form evolves a force.” American buildings and places, once built, become social and cultural actors in their own right, shaping how Americans understand themselves and their place in the world.

Our aims are several. We want to give readers a glimpse into the lively public conversations that have taken place over the course of the nation’s history about the built environment. More boldly, we want this anthology to help reimagine American architectural history by tying it to the broader themes in American social, cultural, and intellectual history. Perhaps most important of all, we hope that this collection gives readers the critical tools with which they can not only evaluate the state of their own built environments but also start to change it. Our premise, though it may sound straightforward, is that architecture should serve the needs of a larger society and should advance its ideals—in the words of Ralph Erskine, “The job of buildings is to improve human relations: architecture must ease them, not make them worse.” The selections we have made all wrestle in one way or another with that fundamental issue.

We begin late in the eighteenth century with the ratification of the Constitution and the founding of the nation in order to make clear this assertion: The quest to define a unique and distinctively American approach to the built environment has undergirded the designing of homes, the building of cities and towns, and the way nature and human activity have been merged. While the traditions of earlier architectures were not forgotten or abandoned, the political, military, and intellectual acts that culminated in 1789 did create a new context for the discussion of architecture and its meaning. We bring our consideration up to the end of the twentieth century both to chart the ways in which the discussion of architecture has shifted over the course of two centuries and to notice how many of the issues raised at the birth of the republic remain live today.

That there is not now nor has there ever been a final answer to the question “What is an American architecture?” goes almost without saying. What the voices collected here demonstrate, disparate as they are, is that the search for an “American architecture” has been the central idea animating what Americans have built.

To illuminate these questions, we have relied a great deal on newspaper clippings, articles from popular magazines, travelogues, and even the occasional novel. Absent, or nearly so, are pieces written by architects speaking to other architects. It merits remembering that while building is eternal, architecture as a profession is quite young. The vast majority—upwards of 90 percent according to some estimates—of buildings and designed landscapes in the United State have been built without professional assistance. They are the products of pattern books, local builders, and individual imaginations. Since our interest is in the relationship between the built environment and other social issues, we have looked to popular, mass venues of communication. The voices here, many of them, are ordinary, largely unknown, and in some cases anonymous. In this way, we hope we have recreated some of the popular conversations that have taken place around architecture and not merely recapitulated the concerns of professionals. In the course of our researches, we have been struck by just how much writing there has been, in all sorts of places, about the built environment; indeed, we collected far more material for this volume than could ultimately fit! We make no claim that this represents a comprehensive collection, but we do think it will give readers a representative sense of how Americans have discussed their built environment at different moments in our history.

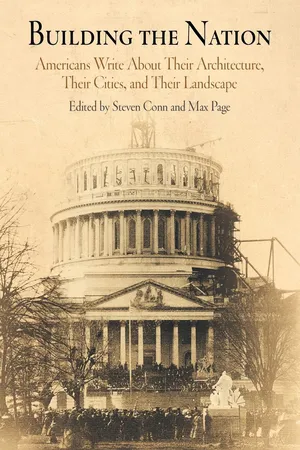

Some readers may be stunned to find that Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater is not discussed here. Nor are most of the buildings we have come to regard as iconic: not Louis Sullivan’s Wainwright Building in Chicago or Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in New York. Where we present a document about the U. S. Capitol, it is not to delineate the classical references in the friezes or to sort out which architect did what on the building. Rather it is to discuss how that building in that city proposed to embody the very ideals of the nation itself. In some senses, this book is a documentary history of the nation’s built environment that joins some of the more recent histories written by scholars like Vincent Scully, John Stilgoe, Dolores Hayden, Gwendolyn Wright, Daniel Bluestone, and others who have broadened our understanding of the built environment beyond a particular set of architects and a canonical set of buildings. Other areas of American history have benefited in recent years from volumes of primary documents, and while there a few fine volumes of documents on architecture—notably Don Gifford’s Literature and Architecture (1966), Leland Roth’s America Builds (1983), and Joan Ockman’s Architecture Culture (1993)—none takes the comprehensive and historically grounded approach to the built environment that we have provided here.

This book is organized into eight chapters, each dealing with a different theme. Documents within each chapter span both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Each chapter begins with our brief introduction, sketching the issues to be considered and tracing their chronological trajectory. These introductions also glance at some larger cultural, social, and intellectual developments relevant to the topic. Readers will find that each document is introduced briefly as well.

We begin, then, in Chapter 1 with a series of writings very broad in their scope, which seek to address the nature of American architecture as a whole. Architecture, perhaps more than any of the fine arts, embodies the values, tastes, and ambitions of a culture: How might one create an architecture that would give physical form to the new nation’s aspirations? Sweeping statements, these writings consider American architecture and its relationship to the state of the nation at particular moments—the country’s founding, for example, or its crisis in the 1930s. As the nation developed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Americans who wrote about architecture believed that the new nation demanded a new architecture, one commensurate with the boldness of the American political experiment. They asked questions about what a “democratic” architecture should be and about how American cities could avoid the “corruption” of their European counterparts. Americans, especially in the nineteenth century, surveyed the history of architecture trying to figure out what, exactly, from architecture’s past could be appropriated to build an American future. Indeed, as architectural critic and historian Joseph Rykwert has pointed out, the most vigorous architectural debates of the nineteenth century revolved around the meanings and appropriateness of different styles. American architects and builders who tried to create buildings to reflect the new nation found themselves relying, perhaps inevitably, on the styles of the past. Later in the nineteenth century, facing a variety of crises—secession and war, chaotic urban growth, the social traumas associated with industrialization—writers continued to talk about architecture as a curative for an ailing nation. In the twentieth century, faced with both the challenges and opportunities of growing national diversity and an increasingly prominent international presence, writers reconsidered how American buildings would reflect the changing populace and democratic ideals.

Americans have always had a strained cultural relationship with Europe, and Chapter 2 provides a window through which to view that. Travel writings of Europeans who visited the United States and wrote, often disparagingly, about their findings have become familiar to readers. Less well known are the writings of Americans who went back across the Atlantic looking for sources of cultural inspiration, hoping to bring European design ideas back to the United States. The essays included in this chapter reveal how, through the nineteenth and much of the twentieth centuries, the cultural traffic went largely in one direction between Europe and the United States, as many Americans felt they lived in Europe’s shadow. By the latter half of the twentieth century, however, writers discuss how American ideas and forms began to proliferate around the globe and the rest of the world began to take on a decidedly American cast.

At some level, America exists more powerfully in the imagination as a landscape. Just as Americans debated the proper way to design individual buildings and how to build better cities, they wondered about how to shape the vast natural landscape they saw stretching before them, and Chapter 3 fleshes out these debates. On one hand, Americans viewed the natural world they saw as their birthright, as an almost limitless arena for the development of cities and commerce, as resources to be exploited. On the other hand, they looked to the landscape, almost reverentially, as the reservoir of moral power and as the source of democracy’s reinvigoration, and they worried about what would happen to America as the loss of landscape continued apace. By the end of the twentieth century, many lamented that, except in a few preserves, the American landscape had been reduced to a homogenized lowest common denominator, a landscape of banality and sameness.

Too often discussion of American architecture has focused on the buildings of the Northeast, as if this region spoke for the entire nation. Chapter 4 stands as a corrective to this regional bias. Through much of the nation’s history, the United States might better be viewed as three regions—North, South, and West—with numbers of smaller regions within these. By shifting the lens through which we examine questions of the built environment to different regions of the country, we hope to broaden and complicate our thinking about the diversity of American architecture and space. The writings included in this chapter also reveal that regional distinctiveness in architecture, like the American landscape itself, had eroded dramatically by the end of the twentieth century.

Chapter 5 focuses on the debates over visions of America as an urban nation. Central to this debate was both the repulsion and attraction Americans felt—and continue to feel—about their cities. Attempts to reconcile this simultaneous enthusiasm and suspicion included efforts to redesign cities with park and parkway plans, utopian settlements in rural areas, and temporary urban fantasies embodied most powerfully in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and more recently by Disney’s theme park cities.

In Chapter 6, we give special attention to the suburbs, which have come to be the dominant type of housing settlement in the United States since the 1950s. In 1980, the federal census announced that the United States had become a suburban nation, with a majority of us living in these “in between” places rather than in cities or in rural areas. Chapter 6 considers the American suburb. Even as America was building its great cities in the nineteenth century, it was also developing the ideology and forms of a new type of settlement. Originally the suburb was conceived of in the nineteenth century as a place where one could have the benefits of both city and country, where carefully planned picturesque natural beauty might be only a brief train ride from the bustle of downtown. In the twentieth century, the automobile changed profoundly how the suburb was built and how it functioned; after the Second World War, suburban sprawl began in earnest, fueled in part by a perception that American cities were in crisis. Postwar suburbanization has transformed the American landscape—both the physical and the political landscape—more profoundly and more quickly than any other phenomenon in American history. We are only just beginning to tally the consequences.

Chapter 7 looks at the American impulse to reform both individuals and society through architecture. In the nineteenth century, environmental factors replaced essentialist and theological ones as explanations for human behavior, both good and bad. Bad people, once thought to be bad intrinsically, were now believed to be bad because of the circumstances that surrounded them. As a result of this intellectual shift, many Americans became what we might call “architectural determinists.” For them bad buildings produced bad people; good buildings would produce good ones. Schools, properly designed, would generate better students; proper houses led to proper families; prisons built according to the right principles would reform criminals. In the twentieth century, the religious roots of this reforming instinct became less overt, but the belief that physical design would create better citizens and foster healthier communities persisted.

We conclude with a chapter dealing with how Americans have preserved the past in the built environment. It was during the nineteenth century that Americans developed a distinctive historical consciousness. This presented something of a paradox because the United States was both celebrated and derided as a nation without history. The nascent movement for historic preservation was driven by an urgency that the physical remains of America’s history were disappearing, victim in many cases to the very economic “progress” Americans lauded. This movement grew in the late nineteenth century and exploded into a national phenomenon by the mid-twentieth century. The writings in Chapter 8 illustrate how Americans attempted to embody a sense of the past in the built environment, and how Americans debated which pasts were worthy of saving in the first place.

The issues around which we have organized this volume themselves represent certain choices we have made and issues we want to emphasize. Like any categorization, these chapters focusing on these issues are to some extent artificial; they certainly do not mirror perfectly the writings we have included. As a consequence many of these pieces speak to two or even more of the chapters—an essay we have included in the chapter on landscape, for example, might have much to say about regionalism; issues of urbanism and suburbanization are necessarily intertwined. Drawing connections between chapters and issues is part of what we hope will be fun for readers.

Over the course of many centuries, and perhaps more so than any other cultural production, architecture has prompted some angry, vitriolic polemics, couched often in the language of ethics and morality. And although not all the voices that populate this volume ring out with that kind of invective, this collection does have a point of view. Or several. Ostensibly anthologies are merely collections of other people’s work. But in fact every anthology bears the strong imprint of its editors. The selection of documents and the way they are arranged, edited, and introduced all shape an underlying argument the editors want to make. This is as it should and must be. We would like to make the implicit explicit, however, and lay out for readers now some of the motivations that lie behind this book and that prompted us to put it together.

To begin, we are skeptical of the architectural determinism mentioned above if it means that difficult, complicated problems of social justice and inequalities generate only design solutions. We don’t believe that architecture can solve social problems without serious attention to the other causes of those problems. At the same time, however, we share a strong belief in the power of architecture to shape people’s lives, to destroy or invigorate communities. Good buildings will not cure all of what ails this society, but they are surely part of the solution.

We believe that the varieties of America’s natural landscape have been one of the main sources of what is and has been powerful and unique about American life, whether for Henr...