![]()

The Great Contraction, 1929–1933

by Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz

![]()

PREFACE

THE COLLAPSE of the United States banking system during the course of the business contraction from 1929 to 1933 and the failure of monetary policy to stem the contraction had a profound influence on men’s ideas. In the worlds of scholarship and policy alike, these events led to the view that monetary phenomena primarily reflect other economic forces and that money plays at most a minor independent role in economic affairs. The inference was drawn that policy designed to prevent or moderate economic fluctuations must assign major emphasis to governmental fiscal action and direct intervention.

A paradoxical result followed from the influence of the monetary events of 1929–33 in shaping men’s ideas about money. The view that money plays only a minor role in economic affairs led, for several decades, to the virtual neglect of the study of monetary phenomena, including the monetary events of 1929–33. Only recently has there been a renewal of interest in this field of study. Accordingly, we were led to devote a lengthy chapter to the climactic four-year period of the Great Contraction in our book, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Indeed, one-sixth of the book is devoted to just these four of the ninety-four years our analytical narrative covers.

We concluded that the wrong inference had been drawn from the experience of those four years, that the experience was a tragic testimonial to the importance of monetary forces, rather than evidence of their unimportance. The drastic decline in the quantity of money during those years and the occurrence of a banking panic of unprecedented severity were not the inevitable consequence of other economic changes. They did not reflect the absence of power on the part of the Federal Reserve System to prevent them. Throughout the contraction, the System had ample powers to cut short the tragic process of monetary deflation and banking collapse. Had it used those powers effectively in late 1930 or even in early or mid-1931, the successive liquidity crises that in retrospect are the distinctive feature of the contraction could almost certainly have been prevented and the stock of money kept from declining or, indeed, increased to any desired extent. Such action would have eased the severity of the contraction and very likely would have brought it to an end at a much earlier date.

Moreover, the policies required to prevent the decline in the quantity of money and to ease the banking difficulties did not involve radical innovations. They involved measures of a kind the System had taken in earlier years, of a kind explicitly contemplated by the founders of the System to meet precisely the kind of banking crisis that developed in late 1930 and persisted thereafter. They involved measures that were actually proposed and very likely would have been adopted under a slightly different bureaucratic structure or distribution of power, or even if the men in power had had somewhat different personalities. Until late 1931—and we believe not even then—alternative policies did not involve any conflict with the maintenance of the gold standard.

Robert M. Tayler, an undergraduate at Earlham College, who read our book, suggested to us the desirability of reprinting as a paperback the chapter in A Monetary History on “The Great Contraction, 1929–33,” so that it would be readily available as supplementary reading for college courses that deal with that episode. We are grateful to him for the suggestion and to Princeton University Press for acting on it.

Though “The Great Contraction” is reasonably self-contained and can be understood without reading the chapters that precede or follow it in A Monetary History, as a convenience to readers of this paperback reprint, we have included a glossary of terms and full source notes to figures.

One regrettable omission here is acknowledgment of the numerous and heavy debts we incurred to many individuals and institutions for assistance in the course of writing A Monetary History. For a partial list, we must refer the reader to the preface of the book.

Comments by Albert J. Hettinger, Jr., a director of the National Bureau, that appear at the end of A Monetary History are reprinted here, since they deal mainly with this chapter.

M. F.

A. J. S.

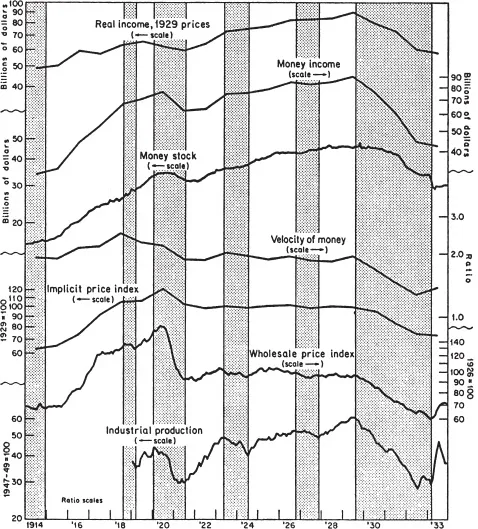

FIGURE 1

Money Stock, Income, Prices, and Velocity, in Reference Cycle Expansions and Contractions, 1914–33

NOTE: Shaded areas represent business contractions; unshaded areas, business expansions.

SOURCE: Industrial production, seasonally adjusted, from Industrial Production, 1959 Revision, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 1960, p. S-151 (manufacturing and mining production only). Other data, same as for Chart 62.

![]()

THE GREAT CONTRACTION 1929–33

THE CONTRACTION from 1929 to 1933 was by far the most severe business-cycle contraction during the near-century of U.S. history we cover and it may well have been the most severe in the whole of U.S. history. Though sharper and more prolonged in the United States than in most other countries, it was worldwide in scope and ranks as the most severe and widely diffused international contraction of modern times. U.S. net national product in current prices fell by more than one-half from 1929 to 1933; net national product in constant prices, by more than one-third; implicit prices, by more than one-quarter; and monthly wholesale prices, by more than one-third.

The antecedents of the contraction have no parallel in the more than fifty years covered by our monthly data. As noted in the preceding chapter, no other contraction before or since has been preceded by such a long period over which the money stock failed to rise. Monetary behavior during the contraction itself is even more striking. From the cyclical peak in August 1929 to the cyclical trough in March 1933, the stock of money fell by over a third. This is more than triple the largest preceding declines recorded in our series, the 9 per cent declines from 1875 to 1879 and from 1920 to 1921. More than one-fifth of the commercial banks in the United States holding nearly one-tenth of the volume of deposits at the beginning of the contraction suspended operations because of financial difficulties. Voluntary liquidations, mergers, and consolidations added to the toll, so that the number of commercial banks fell by well over one-third. The contraction was capped by banking holidays in many states in early 1933 and by a nationwide banking holiday that extended from Monday, March 6, until Monday, March 13, and closed not only all commercial banks but also the Federal Reserve Banks. There was no precedent in U.S. history of a concerted closing of all banks for so extended a period over the entire country.

To find anything in our history remotely comparable to the monetary collapse from 1929 to 1933, one must go back nearly a century to the contraction of 1839 to 1843. That contraction, too, occurred during a period of worldwide crisis, which intensified the domestic monetary uncertainty already unleashed by the political battle over the Second Bank of the United States, the failure to renew its charter, and the speculative activities of the successor bank under state charter. After the lapsing of the Bank’s federal charter, domestic monetary uncertainty was further heightened by the successive measures adopted by the government—distribution of the surplus, the Specie Circular, and establishment of an Independent Treasury in 1840 and its dissolution the next year. In 1839–43, as in 1929–33, a substantial fraction of the banks went out of business—about a quarter in the earlier and over a third in the later contraction—and the stock of money fell by about one-third.1

The 1929–33 contraction had far-reaching effects in many directions, not least on monetary institutions and academic and popular thinking about the role of monetary factors in the economy. A number of special monetary institutions were established in the course of the contraction, notably the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the Federal Home Loan Banks, and the powers of the Federal Reserve System were substantially modified. The contraction was shortly followed by the enactment of federal insurance of bank deposits and by further important modifications in the powers of the Federal Reserve System. It was followed also by a brief period of suspension of gold payments and then by a drastic modification of the gold standard which reduced it to a pale shadow of its former self (see Chapter 8).

The contraction shattered the long-held belief, which had been strengthened during the 1920’s, that monetary forces were important elements in the cyclical process and that monetary policy was a potent instrument for promoting economic stability. Opinion shifted almost to the opposite extreme, that “money does not matter”; that it is a passive factor which chiefly reflects the effects of other forces; and that monetary policy is of extremely limited value in promoting stability. The evidence summarized in the rest of this chapter suggests that these judgments are not valid inferences from experience. The monetary collapse was not the inescapable consequence of other forces, but rather a largely independent factor which exerted a powerful influence on the course of events. The failure of the Federal Reserve System to prevent the collapse reflected not the impotence of monetary policy but rather the particular policies followed by the monetary authorities and, in smaller degree, the particular monetary arrangements in existence.

The contraction is in fact a tragic testimonial to the importance of monetary forces. True, as events unfolded, the decline in the stock of money and the near-collapse of the banking system can be regarded as a consequence of nonmonetary forces in the United States, and monetary and nonmonetary forces in the rest of the world. Everything depends on how much is taken as given. For it is true also, as we shall see, that different and feasible actions by the monetary authorities could have prevented the decline in the stock of money—indeed, could have produced almost any desired increase in the money stock. The same actions would also have eased the banking difficulties appreciably. Prevention or moderation of the decline in the stock of money, let alone the substitution of monetary expansion, would have reduced the contraction’s severity and almost as certainly its duration. The contraction might still have been relatively severe. But it is hardly conceivable that money income could have declined by over one-half and prices by over one-third in the course of four years if there had been no decline in the stock of money.2

1 For an interesting comparison of the two contractions, see George Macesich, “Monetary Disturbances in the United States, 1834–45,” unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, June 1958.

2 This view has been argued most cogently by Clark Warburton in a series of important papers, including: “Monetary Expansion and the Inflationary Gap,” American Economic Review, June 1944, pp. 320, 325–326; “Monetary Theory, Full Production, and the Great Depression,” Econometrica, Apr. 1945, pp. 124–128; “The Volume of Money and the Price Level Between the World Wars,” Journal of Political Economy, June 1945, pp. 155–163; “Quantity and Frequency of Use of Money in the United States, 1919–45,” Journal of Political Economy, Oct. 1946, pp. 442–450.

![]()

1. THE COURSE OF MONEY, INCOME, PRICES, VELOCITY, AND INTEREST RATES

Figure 1, which covers the two decades from 1914 to 1933, shows the magnitude of the contraction in the perspective of a longer period. Money income declined by 15 per cent from 1929 to 1930, 20 per cent the next year, and 27 per cent in the next, and then by a further 5 per cent from 1932 to 1933, even though the cyclical trough is dated in March 1933. The rapid decline in prices made the declines in real income considerably smaller but, even so, real income fell by 11 per cent, 9 per cent, 18 per cent, and 3 per cent in the four successive years. These are extraordinary declines for individual years, let alone for four years in succession. All told, money income fell 53 per cent and real income 36 per cent, or at continuous annual rates of 19 per cent and 11 per cent, respectively, over the four-year period.

Already by 1931, money income was lower than it had been in any year since 1917 and, by 1933, real income was a trifle below the level it had reached in 1916, though in the interim population had grown by 23 per cent. Per capita real income in 1933 was almost the same as in the depression year of 1908, a quarter of a century earlier. Four years of contraction had temporarily erased the gains of two decades, not, of course, by erasing the advances of technology, but by idling men and machines. At the trough of the depression one person was unemployed for every three employed.

In terms of annual averages—to render the figures comparable with the annual income estimates—the money stock fell at a decidedly lower rate than money income—by 2 per cent, 7 per cent, 17 per cent, and 12 per cent in the four years from 1929 to 1933, a total of 33 per cent, or at a continuous annual rate of 10 per cent. As a result, velocity fell by nearly one-third. As we have seen, this is the usual qualitative relation: velocity tends to rise during the expansion phase of a cycle and to fall during the contraction phase. In general, the magnitude of the movement in velocity varies directly with the magnitude of the corresponding movement in income and in money. For example, the sharp decline in velocity from 1929 to 1933 was roughly matched in the opposite direction by the sharp rise during World War I, which accompanied the rapid rise in the stock of money and in money income; and, in the same direction, by the sharp fall thereafter accompanying the decline in money income and in the stock of money after 1920. On the other hand, in mild cycles, ...