![]()

CHAPTER 1

Welcome to the Monarchy

You who go through the day

like a wingèd tiger

burning as you fly

tell me what supernatural life

is painted on your wings

so that after this life

I may see you in my night

—Homero Aridjis, “To a Monarch Butterfly”

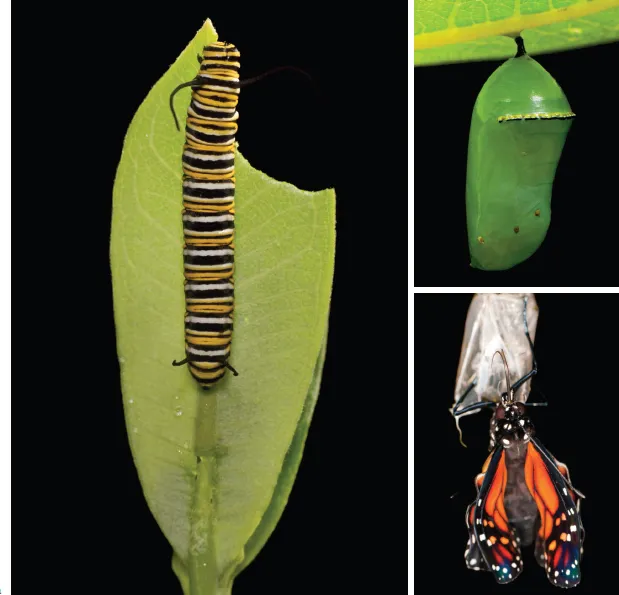

The monarch butterfly is a handsome and heroic migrator. It is a flamboyant transformer: an egg hatches into a white, yellow, and black-striped caterpillar; then a metamorphosis takes place inside its leafy-green chrysalis, which is endowed with gold spots; the adult butterfly that emerges flaunts orange and black (fig. 1.1). In the monarchs’ annual migratory cycle—perhaps the most widely appreciated fact about them—individual butterflies travel up to five thousand kilometers (three thousand miles), from the United States and Canada to overwintering grounds in the highlands of Mexico. After four months of rest, the same butterflies migrate back to the United States in the spring. Come summer, their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren will populate the northern regions of America.

But there is much more to the monarch’s story than bright coloration and a penchant for epic journeys. For millions of years, monarchs have engaged in an evolutionary battle. The monarch’s foe in this struggle is the milkweed plant, which takes its name from the sticky white emissions that exude from its leaves when they are damaged. The monarch-milkweed confrontation takes place on these leaves, which monarch caterpillars consume voraciously, as the plant is their exclusive food source. Milkweeds, in turn, have evolved increasingly elaborate and diversified defenses in response to herbivory. The plants produce toxic chemicals, bristly leaves, and gummy latex to defend themselves against being eaten. In what may be considered a coevolutionary arms race, biological enemies such as monarchs and milkweeds have escalated their tactics over the eons. The monarch exploits, and the milkweed defends. Such reciprocal evolution has been likened to the arms races of political entities that stockpile more and increasingly lethal weapons.

FIGURE 1.1. The monarch butterfly in three stages: (a) a caterpillar eating a milkweed leaf, (b) a chrysalis undergoing metamorphosis, and (c) an emerging butterfly before it expands its wings.

This book tells the story of monarchs and milkweeds. Our journey parallels that of the monarch’s biological life cycle, which starts each spring with a flight from Mexico to the United States. As we follow monarchs from eggs to caterpillars, we will see how and why they evolved a dependency on milkweed and what milkweed has done to fight back (fig. 1.2). We will discover the potency of a toxic plant and how a butterfly evolved to overcome and embrace this toxicity. As monarchs transition to adulthood at the end of the summer, their dependency on milkweed ceases, and they begin their southward journey. We will follow their migration, which eventually leads them to a remote overwintering site, hidden in the high mountains of central Mexico. Along the way, we will detour into the heart-stopping chemistry of milkweeds, the community of other insects that feed on milkweed, and the conservation efforts to protect monarchs and the environments they traverse.

To be sure, this story is about much more than monarchs and milkweeds; these creatures serve as royal representatives of all interacting species, revealing some of the most important issues in biology. As we will see, they have helped to advance our knowledge of seemingly far-flung topics, from navigation by the sun to cancer therapies. We will also meet the scientists, including myself, who study the mysteries of long-distance migration, toxic chemicals, the inner workings of animal guts, and, of course, coevolutionary arms races. We will witness the thrill of collaboration and competition among scientists seeking to understand these beautiful organisms and to conserve the species and the ecosystems they inhabit.

FIGURE 1.2. An unlucky monarch butterfly caterpillar that died after taking its first few bites of milkweed, the only plant it is capable of eating. In a violent and effective defense, toxic and sticky latex was exuded and drowned the caterpillar. A substantial fraction of all young monarchs die this way.

FROM SIMPLE BEGINNINGS

From a single common ancestor, milkweeds diversified in North America to more than one hundred species. And the monarch lineage is no slouch, with hundreds of relatives we call “milkweed butterflies” throughout the world. Although monarchs are perhaps best known in the northeastern and midwestern United States, they occur throughout North America, and self-sustaining populations have been introduced to Hawaii, Spain, Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere (fig. 1.3). Interactions between butterflies and milkweeds now occur throughout the world, but this account focuses primarily on what happens in North America. The reason is quite simple: eastern North America is where the monarch (Danaus plexippus), considered by most to be the pinnacle of milkweed butterflies, coevolved with milkweeds.

The monarch’s annual cycle in eastern North America involves at least four butterfly generations, with individuals crossing international borders several times. In spring, butterflies migrate from Mexico to the southern United States. Flight is fueled by nectaring on flowers and is punctuated by laying eggs on milkweeds. To grow and sustain each generation, milkweed is the only food needed. Three cycles—from egg to caterpillar, to chrysalis, to butterfly—occur as monarchs populate the northern United States and southern Canada each summer. And while nearly all mating, egg-laying, and milkweed eating occurs in the United States and Canada, each autumn monarchs travel to Mexico. At the end of summer, southward migrating monarchs fly thousands of kilometers and then rest for some four months before returning to the Gulf Coast states in the following spring. How and why they do it is a story that continues to unravel, and it no doubt will keep scientists busy for centuries.

The energy that builds a monarch butterfly’s body ultimately comes from plants—as it does for all animals. For most butterflies and moths (collectively, the Lepidoptera), the caterpillar stage is essentially a leaf-eating machine. Perhaps it is not surprising then, that caterpillar feeding has led to the evolution of armament (or “defenses”) in plants. The leaves of nearly all plant species are not only unappetizing to most would-be consumers; they are downright toxic. Milkweed’s toxicity has long been known, and foraging on milkweed has surely killed countless sheep and horses. Most other animals avoid this milky, sticky, bitter weed, and yet monarchs came to specialize on it. While the toxic principles of milkweed keep most consumers at bay, monarchs and a few other insects have craftily adapted to the plant. Humans have used the chemical tonic of milkweeds as medicine for centuries, and so too have monarchs exploited their medicinal properties—at least at low doses. As the great Renaissance scientist Paracelsus noted five hundred years ago, “dose makes the poison”; there is often a fine line between poison and medicine. Much of this book is devoted to unraveling the evolution of poisonous and medicinal properties in plants that are habitual fodder for animals.

The evolutionary war waged between monarchs and milkweed is a product of their intimate relationship. Monarchs not only tolerate milkweed’s toxicity but have evolved to put it to work. For more than a century, insect enthusiasts have observed that most bird predators leave monarchs alone, presumably because their bright coloration signals a toxic body. Nonetheless, monarchs are not free of enemies. Flies and wasps consume them from the inside and eventually burst out. Tiny protozoan parasites infect their bodies, and monarchs medicate themselves with milkweed’s toxins.

FIGURE 1.3. The worldwide distribution of monarch butterflies. Although native to the Americas, they have been introduced to the South Pacific, Australia, and Spain over the past few hundred years. The introduction of weedy milkweeds to these new regions, mostly the tropical milkweed Asclepias curassavica, preceded the establishment of monarchs. Monarchs are most abundant in North America.

The milkweed plant is not a passive victim being devoured by monarchs. When the plant is attacked, its entire physiology, expression of genes, and toxicological apparatus kicks into high gear like an immune system. Milkweeds may lack an animal’s central nervous system, but they possess all the other attributes common to the sessile sugar factories we call plants. They actively engage in strategies that defend against, tolerate, and when possible, manipulate insect enemies like the monarch butterfly.

While some mysteries of monarchs and milkweeds were only recently solved, much of what I present about the interaction between monarchs and milkweeds was reasonably well known (or at least hypothesized) more than a century ago (fig. 1.4). Searching through old newspapers, one can find beautiful accounts of their relationship. Although the classification of the monarch butterfly has changed over the past 150 years, the intimate interaction with milkweed was observed from the very beginning. Monarch “plagues” have been reported for at least as long, frightening entomophobes (people afraid of bugs). Nonetheless, because milkweed is sometimes considered an undesirable weed, an abundance of monarchs was also said to be beneficial by entomologists who knew the insect, as it might control the plant. There were newspaper reports of “Monarch Invasions from Canada” (as they migrated south past Rochester, New York) as early as the 1880s. Although there was some controversy about whether the butterflies migrated long distances, it was solidly hypothesized early in the twentieth century that this insect followed the seasons, south in the autumn, and with multiple generations moving northward each spring. How and why they migrate, and how and why they feed exclusively on milkweed, were discoveries made over the next hundred years. Honestly, they are not fully solved mysteries, but we have made great progress, and this book is about revealing the science behind these discoveries.

Monarchs have also been proposed as a sentinel, whose health as a species may be a “canary in a coal mine” for the sustainability of the North American continent. They travel through vast expanses, tasting their way as they go. Although they tolerate milkweed poisons, they are highly susceptible to others, especially pesticides. Summer and winter climates are likely the key drivers of the monarch’s annual migration: feed on spring and summer milkweed foliage, follow the season north as it is progressively unveiled, rest in the chill mountain air in winter. Their time in Mexico is delicately balanced between being physiologically active, but cool, not burning precious energy before spring arrives. Our changing climate is certainly affecting monarch butterflies, although we are just beginning to understand the severity of these effects.

FIGURE 1.4. A newspaper article about the monarchs’ migration from the Washington Post, September 17, 1911.

In some respects, human activities have enhanced habitat for milkweeds and monarchs north of the overwintering grounds. Logging and agriculture have been good for monarch populations in some regions, like the eastern United States, where these pursuits likely made milkweed and its associated butterflies much more abundant. However, farming surely destroyed much of the midwestern prairie, where milkweed had previously been prolific. Now the same processes, combined with the indirect influences of other human activities, have been suggested as drivers in the decline of monarch butterfly populations. I evaluate what is known about the causes of monarch and milkweed ups and downs toward the end of this book. If they are truly sentinels, then much more than the sustainability of monarchs is at stake, and careful study of their biology—past, present, and future—is in order.

GETTING INFECTED

How ecological interactions—plants and insects, monarchs and milkweeds—caught my attention is a story in and of itself. I grew up in a fairly rural area of suburban Pennsylvania, where fields of red clover and foxtail grasses were common, and my brother and I were encouraged to spend much of our time outside. Vacations were spent camping; my mother was, and continues to be, an insatiable gardener; and the corn fields growing behind my home prompted me to want to be a farmer. As a college student at the University of Pennsylvania, I felt the bliss of self-discovery, yet also the pressures of being a child of immigrant parents who were unfamiliar with most academic endeavors outside of medicine and engineering. My parents’ proviso concerning my college education was that, in addition to exploring my interests in social science and the humanities, I take introductory science and math classes, so as not to close too many doors. Fair enough.

As a sophomore, I decided to take introductory biology. But, because the lecture halls were limited in their seating, and because many colleges feel pressure to have smaller classes (after all, small classes enhance students’ learning, as well as college rankings), there were two offerings of the course that semester—similar classes, covering much the same material, but taught by different professors. To choose, I did what many students did, and still do: I consulted what was known as a “skew guide,” a “for the students, by the students,” survey of courses that outlined the degree of difficulty, what was liked and disliked by students who had taken the course previously, and unashamed caricatures of the esteemed faculty—the clothes they wore, comments about their hygiene, and notes about their traits, usually having little to do with their ability to impart scholarly information. Sad but true, what sealed the deal for me was the characterization of one of the professors: “typically comes late to class and leaves early.” I actually don’t remember if that ended up being true, but the course, and his approach to biology, caused a profound shift in my own development as a student. Dr. Daniel Janzen presented biology as a set of stories, far stranger than any science fictio...