![]()

BOOK TWO

AT HOME

![]()

PART III

THE SECOND COMING

![]()

9

THE ETERNAL HOUSE

In September 1929, the “proletarian” literary journal October published Andrei Platonov’s story “Doubting Makar.” Makar is a peasant who, like all peasants, “does not know how to think because he has an empty head over clever hands.” Makar’s village chairman, Comrade Lev Chumovoi, on the other hand, does a lot of thinking because he has “a clever head, but empty hands.” One day Makar makes iron ore out of mud, but soon forgets how he did it. Comrade Chumovoi punishes him with a large fine, and Makar sets off for Moscow “to earn himself a living under the golden heads of all the temples and leaders”:

“Just where exactly is the center around here?” Makar asked the militiaman.

The militiaman pointed downhill and informed him:

“Next to the Bolshoi Theater, in that gully down there.”

Makar descended the hill and found himself between two flower beds. On one side of the square was a wall, on the other, a building with pillars. These pillars were holding up four harnessed iron horses, but they could have been a lot thinner since the horses were not very heavy.

Makar looked around the square searching for some kind of pole with a red flag, which would indicate the middle of the central city and the center of the entire state, but instead of a pole there was a stone with an inscription on it. Makar propped himself against the stone in order to stand at the very center and experience a feeling of respect for himself and his state. Makar sighed happily and began to feel hungry. He walked down to the river where he saw an amazing apartment building being built.

“What are they building here?” he asked a passerby.

“An eternal house of iron, concrete, steel, and clear glass!” responded the passerby.

Makar decided to drop by in order to do a bit of work and get something to eat.

There was a guard at the door. The guard asked:

“What do you want, blockhead?”

“I’m a bit on the hollow side, so I’d like to do a little work,” declared Makar.

“How can you work here when you don’t have a single permit?” said the guard sadly.

At this point a bricklayer came up and started listening eagerly to Makar.

“Come to the communal pot in our barracks—the boys there will feed you,” said the bricklayer to Makar helpfully. “But you can’t sign up with us right away because you live on your own, which means you’re a nobody. You’ve got to join the workers’ union first, and then undergo class surveillance.

And so Makar went to the barracks to eat from the common pot in order to nurture himself for the sake of a better future fate.1

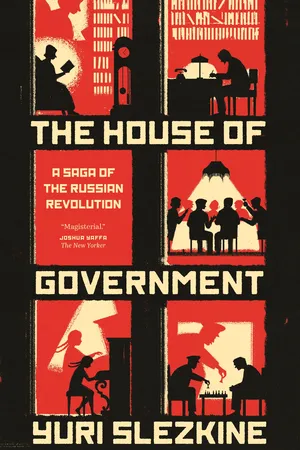

The eternal house they were building was officially called the House of the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars, commonly known as the House of Government. It was designated for leaders with golden heads and designed by a man named Boris Iofan.

For most of the 1920s, top-ranking Soviet officials had been camping out in hotels and palaces converted into dormitories (Houses of Soviets). Everyone knew that the arrangement was temporary: the Left expected the imminent death of all domesticity; the Right looked forward to turning the Houses of Soviets into proper homes; and the growing contingent of foreign visitors required “large, well-appointed hotels with large comfortable suites of two to three rooms, with a bath, etc.” (The most desirable were the First and Second Houses of Soviets, formerly the National and the Metropol Hotels.)2

In January 1927, when the Right was still on the rise, Rykov, in his capacity as head of government, formed a Commission for the Construction of the House of the Central Executive Comittee and Council of People’s Commissars and appointed Boris Iofan head architect. Iofan was born in an Odessa Jewish family in 1891, received an Odessa Art School diploma in 1911, worked as an assistant architect in St. Petersburg, and, in 1914, emigrated to Italy, where he graduated from the Higher Institute of the Fine Arts in Rome and started practicing as an architect. In 1921 he joined the Italian Communist Party and, in 1924, acted as cicerone to the visiting Rykov family. Later that year, he had accepted Rykov’s invitation to return to Russia. His first two projects were a garden city for the workers at the Shterovskaia Hydroelectric Dam in Ukraine (1924) and a communal workers’ settlement on Rusakov Street in Moscow (1925). No other architect was considered for the House of Government commission.3

At its first meeting on January 20, 1927, the commission, chaired by Central Committee Secretary Avel Enukidze, decided to build the House of Government between the Nikitskie Gates and Kudrinskaia Square. It was to be seven stories: the ground floor was to be occupied by shops, the rest to be divided into two wings: one with three-room apartments, the other, with five-room apartments (two hundred apartments in all). The House was to be “open from all four sides” and to possess “high-quality” facilities, including central heating, parquet floors, hot water, and gas stoves. It was to be built of reinforced concrete, with brick walls and a metal roof; the construction was to be completed by the fall of 1928; the total cost was to be three million rubles.4

A month later, the commission decided to double the overall number of apartments, add some four-room apartments, supply the five-room apartments with special rooms for servants, double the total cost, and move the location to Starovagankovsky Alley, next to the Central Archive (the site of the future Lenin Library). Three weeks later, the commission decided to tear down the Central Archive. Two and a half months later, on June 24, 1927, it made “the final decision” to build the House of Government in the Swamp.5

The new location had some serious disadvantages. Building a large structure in the Swamp meant that the ground level had be raised (by at least half a meter above the level of the 1908 flood, or about 10.57 meters overall), the embankment reinforced, and the building itself supported (by about three thousand reinforced concrete piles, sunk into the bedrock five to fifteen meters below). The extra cost and effort were deemed justifiable, however, because of the site’s proximity to government offices and its relatively low density of development. The clearing of the area involved the closure of the Wine and Salt Yard, the relocation of the Regional Courthouse (the former Assembly of the Justices of the Peace), the tearing down of three residential buildings and more than twenty warehouses, the eviction of approximately one hundred permanent residents, and the transfer of the lumber yard belonging to the Electric Tram Power Station to the territory of the former Smirnov Vodka Factory.

A few months later, the Construction Commission also decided to straighten All Saints Street and demolish the Swamp Market (beginning with the stone and metal warehouses and the public toilet). At the same time, Iofan asked Enukidze’s permission to tear down the Church of St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker in order to build a detached kindergarten and day-care center. The State Historical Preservation Workshop, which was housed inside St. Nicholas, put up a strong resistance, claiming that the church was a part of the seventeenth-century Averky Kirillov Residence, and thus a much needed reminder of “the mutually advantageous proximity of religion and the ruling class” under the old regime. More to the point, they argued that the territory of the church was not large enough for a proper House of Government children’s facility complete with sunlit gardens and playgrounds. The Central Executive Committee ordered the Historical Preservation Workshop to vacate the premises, but then concurred with the size argument and decided to incorporate the children’s facility into the House of Government No. 2, to be built on the site of the former Swamp Market. The church was spared (and the second House of Government was never built).6

On April 29, 1928, the Moscow Regional Engineering Bureau issued a permit authorizing construction. The building was to be made of reinforced concrete with outer walls of brick. The bureau “considered it possible to allow, by way of exception, the construction of residential buildings ten stories high, instead of six, as prescribed by a binding regulation of the presidium of the Moscow City Soviet, with each stairway serving twenty apartments, instead of twelve, as prescribed by the same regulation.” The proposed complex consisted of seven attached residential buildings varying in height from eight to eleven stories, a movie theater for 1,500 people, a grocery store, and a club for 1,000 people, containing a theater, cafeteria, and various sports facilities. It stretched the length of All Saints Street from the Drainage Canal to the Bersenev Embankment, and was centered on three landscaped courtyards connected by tall archways.7

The residential wings were to include 440 three-, four-, and five-room apartments, not counting the special rooms set aside for the janitors and guards. Each apartment was to have a kitchen with gas stove and icebox, a toilet, a bathroom with hot water and shower, a ventilation system, a garbage chute, hot water radiators in special niches under the windows, and a large entrance hall that could be partitioned into two separate spaces, one of which “could serve as a place where servants could rest.” All garbage was to be burned in basement incinerators, “liquids and feces” evacuated into the municipal sewage system, and snow melted in special concrete pits and drained into the river. The laundry was to be located in a separate building.8

Bersenev Embankment. The building on the right is being torn down in preparation for the construction work.

House of Government construction site (facing the Kremlin)

The sinking of the piles began on March 24, 1928. The piles (3,520 altogether) were delivered to the site by three traveling cranes and lifted onto eight pile-driving rigs by electric winches; the same winches were used for hoisting the steam pile hammers, which ranged from two thousand to twelve thousand kilograms in weight. Cement mixers were placed in special carts and transported as needed. Sand and gravel were sorted and washed on the other side of the Ditch and delivered to the site by means of an aerial tramway. Much of the equipment had been transferred to the Swamp from the newly completed Volkhov Hydroelectric Dam. The workers came from the Moscow Employment Office or just wandered in.9

Makar settled into the life of the building of the house the passerby had called eternal. First he ate his fill of nutritious, black kasha in the workers’ barracks, and then went to look at the construction work. All around, the earth was scarred with pits, people were scurrying about, and machines of unknown name were driving piles into the soil. Cement gruel was pouring from spouts, and other productive events were also taking place before one’s eyes. It was obvious that a house was being built, but not clear for whom. But Makar was not interested in who was going to get what: he was interested in technology as a future boon for all the people. Makar’s commander from his native village, Comrade Lev Chumovoi, would, on the contrary, have become interested in the distribution of apartments in the future house, and not in the steam pile hammers, but only Makar’s hands were literate, and not his head; therefore, all he could think about was what he could make.10

Most workers were like Makar: seasonal laborers who came to Moscow to get away from Comrade Lev Chumovoi and to “nurture themselves for the sake of a better future fate.” This called for special vigilance: the bricklayer who tells Makar that he will have to join the workers’ union first, and then undergo class surveillance knows what he is talking about. The Construction Workers’ Union warned repeatedly that “the presence, among the unemployed, of a significant number of people who are alien to the Soviet order, do not truly need work, have a permanent income from temporary jobs including petty trade and artisanship, retain close links to the peasant way of life, and possess skills that have not yet been classified, … presents the Moscow Employment Office with the task of carefully checking all the unemployed.” Sixty percent of all union members were seasonal laborers who had to be “watched more closely at the time of hiring and then again in their day-to-day work.” In March 1928, when work on the House of Government was just getting under way, the Trans-Moskva District Party Committee declared that “the most common diseases” among the district’s workers were “(a) vulgar egalitarianism with regard to the city and the countryside, different kinds of workers, workers and specialists, etc.; (b) peasant attitudes (in particular, in connection with grain requisitioning); (c) trade loyalties; (d) mistrust regarding the rationality or feasibility of various campaigns (e.g., the rationalization of work, seven-hour workday, etc.); (e) anti-Semitism; (f) religious beliefs, etc.”11

House of Government construction site (facing the power station)

One way to change the workers’ consciousness was to change their “social being”: the construction commission kept asking for mittens, jackets, pants, guards’ uniforms, “permits for goods in particularly high demand,” and, most urgently, living space. (As of late 1927, “the actual average living space of 5.57 square meters per person” in the Trans-Moskva district “continued to decline owing to the growth of the population and the deterioration of the existi...