![]()

1

BALANCED OBJECTIVITY AND ACCUMULATED AUTHORSHIP

I’m responsible for the complete picture outfit for this ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Basically I have to follow the news, I have to make sure that we cover breaking stories, that we present a complete picture of the conflict from both sides, from both viewpoints. Before I came here, I thought it might be a problem to be a foreigner. In fact I’ve never found it an issue at all. As a foreigner, you stand above the story. To be in charge of the picture operation, it would not be good if you would either be Israeli or Palestinian, nor [would it] be good to be Jewish or Muslim.

Reinhard Krause, Jerusalem Chief of Reuters’ photojournalism department, in Shooting Under Fire1

In the documentary Shooting Under Fire, a staff of Palestinian and Israeli photographers reflect on perspective and national identity:

Nir Elias, Israeli photojournalist, in a room adorned with photographs: It’s obvious that I have a point of view of an Israeli, and they have a point of view of Palestinians. It’s different.

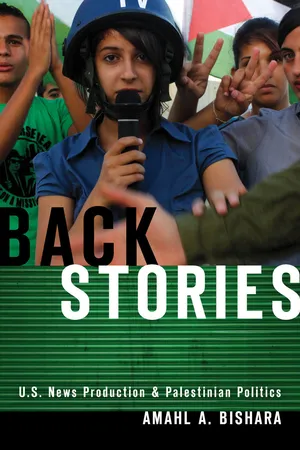

Suhaib Salem, Palestinian photojournalist, wearing a helmet and flak jacket, with displaced people in Gaza: I feel bad, because these people seem like us. We are, all of us . . . Palestinians. OK, I am a journalist, but in the end I am Palestinian.

Gil Cohen-Magen, Israeli photojournalist, in front of the Western Wall: OK, you [on the Palestinian side] believe this, I [as an Israeli] believe this. . . . But we don’t need to fight, we don’t need to kill each other.

Ahmed Jadallah, Palestinian photojournalist, in a living room: Because I am Palestinian, [I am] looking at things in one direction. And the Israeli photographer also. But Reinhard [is] looking at the story from two directions.

Reinhard Krause, editing room: I’m trapped in the middle. I know exactly how it looks like when a bus is torn apart from a suicide bomber, because that happened just a few hundred meters away from our house. And I also have been in Gaza when Gaza was shelled, andI saw [what] it looks like when a missile hits a group of people. . . . And for me, both [are] exactly the same—horrible.2

In these passages the Israeli and Palestinian photojournalists each resign themselves to the provincial perspective of their own nationalities, but Krause is presumed able to “[look] at the story from two directions.” It is from this vantage point that he can conclude that the experience of violence each side suffers is “exactly the same.”

Notably, in this documentary sequence the Israeli, Palestinian, and German photojournalists are not sitting in the same room. Documentarian Mirzoeff has edited together several interviews conducted in different places. Rather than letting the audience hear longer quotes from any of the photographers, he assembles a passage that creates a sense of balance, alternating between a Palestinian and an Israeli. The passage positions Krause, the foreigner, above the fray, giving him the last word at the end of the scene. In this regard, the content subtly mirrors the relationships that made production of the documentary itself possible. Mirzoeff’s assembling of quotes from “both sides” so that they seem to form a mirror image of each other constructs a logic of balance out of material that could be organized in other ways. Both Mirzoeff and Krause are placed in the position of the reasoned outsider between two opposing sides.

This is the logic of what I call balanced objectivity, an incarnation of objectivity characteristic of Western journalism in Jerusalem that at once describes how journalists talk about their work, how their texts are written, and how news bureaus are structured. Balanced objectivity also characterizes an ethic of reporting and writing at this site. Objectivity is what Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison have called an “epistemic virtue,” in that it is a norm “internalized and enforced by appeal to ethical values, as well as to pragmatic efficacy in securing knowledge.”3 Though journalists do not use the term balanced objectivity and instead tend to talk about the related terms of fairness, lack of bias, balance, or objectivity, being objective and creating balanced journalism is regarded as an ethical endeavor, as well as a practical one.

In fact, the Israeli and Palestinian photojournalists in the passage above share more than is suggested by the logic of balanced objectivity, which can tend to polarize and flatten out Israeli and Palestinian viewpoints. In an earlier sequence of the documentary, the Israeli Nir Rosen and the Palestinian Suhaib Salem each independently investigate a new Israeli military fence around a Gaza settlement. They have different visual perspectives on this fence because they see the physical structure from two opposing sides. Since the early 1990s, the Israeli system of closure—made up of checkpoints and other physical means, as well as bureaucratic measures4—has isolated Palestinians from Israelis. The Palestinian photojournalist cannot reach the Israeli side, and the Israeli photojournalist would have to take an uncomfortable and circuitous route to reach the Palestinian side, unless he was with soldiers. This system of closure plays no small role in reinforcing balanced objectivity.

But their political analyses of the significance of the fence do not point to dichotomous nationalist narratives. Instead, both see the fence as a means of Israeli expansion of territorial control. Their analyses contrast with the official Israeli logic behind such fences, that they are built for security reasons. Salem explains, “Every day they come at night, they demolish seven, ten houses, then after this they put wire in this area so no one should get in. After a month, they come to take another area and after another month, another area, like this.” Surely drawing on the experience of living in Gaza and having watched similar processes unfold in other parts of the territory, like the southern border between Gaza and Egypt, he concludes, “Anyone who comes to this area after one month, where we are staying here . . . they will shoot him immediately because it’s going to be close to the army post.”5 The Israeli journalist Rosen confirms this argument. “Maybe [the Israeli authorities] want to push a little, to push the crossing . . . a little inside and then stop it, and then say, ‘Gaza finishes there, not there.’”6 Israeli and Palestinian perspectives—and here I mean embodied points of views on the world—are divergent, because geographic separation between them has been so stringently executed, but that does not mean that their political analyses are always dichotomous. Perhaps because Mirzoeff’s documentary allows us to hear at length from Israeli and Palestinian photojournalists, it permits this brief disruption of the norm of balanced objectivity.

“BALANCED OBJECTIVITY” AS VALUE AND STRATEGY

What does it mean to qualify the term objectivity as “balanced”? Objectivity might be considered one of what Timothy Mitchell has called the “principles true in every country,” a bedrock of modern science and government, even though in fact it has a particular history, like other such ideas.7 He aims to question the universality of such principles as the economy and development. Similarly, objectivity has authority because of its apparent unity as a concept. In this way, objectivity is like other seemingly universal categories that have seemed to originate in abstract Western thought, but that in fact have taken shape by way of the execution of real world projects in colonial and postcolonial contexts.8 Indeed, there has been great variation in how those in different fields have defined objectivity. Historian Lorraine Daston has demonstrated that the concept of objectivity hardly refers to a clear standard or a single coherent idea. Its meanings over different historical periods have included aperspectivity, multiperspectivity, suppression of judgment, rejection of aestheticization, and reference to an ontological bedrock.9 As Charles Briggs has found, these disparate meanings are linked by a deeply engrained “folk epistemology [that conceives] of ‘the truth’ as being singular, unequivocal, and semantically transparent.”10

Likewise, the methods of producing objective knowledge vary across fields like the social sciences, biology, and journalism. Max Weber argued that objectivity in the social sciences is not value-free, writing that “an attitude of moral indifference has no connection with scientific ‘objectivity,’”11 but, he proposed, objective knowledge should be universal, unconnected to culture or nationality: “A systematically correct scientific proof . . . must be acknowledged as correct even by a Chinese.”12 In visual anthropology, Margaret Mead asserted that using a tripod and taking long shots produced suitably “scientific” footage that would serve anthropologists for generations to come.13 In their study of visual representation in scientific atlases, Daston and Galison demonstrated that objectivity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries entailed, for some scientists, the use of instruments like cameras to forge a “mechanical objectivity” that met “the insistent drive to repress the willful intervention of the artist-author” with procedures and protocols;14 while mathematicians of the same period found objectivity in drawing abstract charts and illustrations whose meanings could be “conveyed to all minds across time and space.”15

Journalism adopted objectivity as an epistemic virtue on the coattails of other fields of knowledge production. Objectivity started to become a central value of American journalism in the mid–nineteenth century, around a time when much of American public culture was orienting itself around science as opposed to faith. Emulating scientific values was a means by which journalists acquired public respect.16 Objectivity also became dominant because of commercial developments in journalism. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, media consolidation left cities and towns with one or possibly two major newspapers rather than the previous era’s multiple papers, which each had a distinct point of view. Publishers thus preferred to attract larger audiences with “objective” news that would sell to people of a variety of political viewpoints.17 Yet objectivity, often parsed as a belief in a single, knowable, and representable truth, was never an ironclad standard. According to historian Michael Schudson, it “seemed to disintegrate as soon as it was formulated,” perhaps because it became the prevailing approach to U.S. journalism in the wake of controversies about World War I propaganda and postwar publicity.18 Even discoveries in the physical sciences—like the Heisenberg uncertainty principle—undermined people’s faith in the human ability to find one complete truth. Objectivity was the accepted value that gave journalism public credibility, even as many practitioners and scholars recognized that objectivity in journalism was hard to define.

Critiques of objectivity in journalism have endured until today,19 even as objectivity remains central to the public face of journalism in the United States. Foreign correspondents’ professed dedication to objectivity may be surprising in a contemporary American news landscape that increasingly seems to thrive on subjectivity, as on cable news. In fact, my interviews revealed that even foreign correspondents working for media companies known for their partisanship were confident that the reporting they did was distinct from the opinionated talk shows on those same networks.

Still, I argue that objectivity varies across different locations even within the same field of American journalism.20 According to journalism scholar David Mindich, American objectivity has been characterized by five traits that emerged sequentially in relation to political events, technological developments, and changes in newspapers’ economic structures: (1) journalists’ detachment from direct involvement in news events, (2) nonpartisanship, (3) the use of an inverted pyramid writing structure that places the most important information at the beginning of a report and that contrasts with a narrative writing style, (4) a stress on empiricism, and (5) balance.21 Yet, in Jerusalem bureaus, balance clearly trumps the other characteristics of objectivity. Elite foreign correspondents are occasionally reflexive about their work in a way that is uncharacteristic of an attitude of detachment. They may write articles that refer to the effects of their own reporting or to their experiences as foreign correspondents, as when a journalist found himself “up close. Too close” to a suicide bombing.22 On returning to the United States, one reporter reflected that her son encountered the toll booth at the Triborough bridge and “asked if we were at the American border”; in response her daughter “chided him, ‘No, silly, it’s just a checkpoint.’”23 Likewise, in relatively frequent feature stories, journalists cast aside the inverted pyramid model in favor of a narrative approach, or use the opening of an article to heighten suspense or the curiosity or sympathy of the reader. We find lyrical articles about a Palestinian militant whose “skin is the color of roasted pecans” from a bomb-making mishap,24 Jewish activists who monitor checkpoints “armed with . . . notebook, mobile phone, and compassion,”25 and the “ghost town” of Bethlehem that houses “abandoned restaurants” with names like Memories, where people are left to “celebrate Christmas behind a wall.”26 Description and interpretation have long been welcome in foreign correspondence because it is assumed that readers need more background and explanation to understand distant places.27 In terms of internal Palestinian and Israeli politics, U.S. journalists are hardly nonpartisan either. Instead, they often exhibit favor for the Israeli and Palestinian parties seen as promoting the U.S.-sponsored negotiations process.28

This leaves balance as an organizing value, and the apparent contours of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—with one group on each side of the hyphen—seem to justify it as a mode of objectivity at this site. Practitioners of balanced objectivity, who may or may not be true believers, do not have to claim to have found the single truth, as long as they have represented “both sides.” To a certain extent, this is a matter of the structure of the “beat,” or the journalistic assignment and its geographic boundaries. As New York Times bureau chief Ethan Bronner said in a February 2010 lecture at Brandeis University, “In the job I do in Jerusalem, the problem is that I have two completely contradictory narratives: the Israeli Jewish narrative and the Palestinian narrative. It’s not like my colleague in, say, Rome, who covers Spain, Portugal, and Italy. She has a bunch of different stories; she has to get used to them. I have black, white, black, white.”29

Talking about balance is a tactic of allaying criticism in this fraught field. The New York Times’ first public editor Daniel Okrent commented, “It’s this simple: An article about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict cannot appear in The Times without eliciting instant and intense response.”30 Foreign correspondents may point to criticism from both sides as the indicator of good journalism. For example, following criticism of an article he wrote about the separation barrier,31 New York Times correspondent Steven Erlanger responded to activist letter writers who argued he had failed to be sufficiently critical of the separation barrier by addressing some of their specific concerns. Then he stated in his defense that the very same piece had generated a vitriolic accusation that he was anti-Israel.32 Despite what Okrent called the paper’s “effort to stick to the noninflammatory middle and to keep things civil,” the polarized atmosphere regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict means that journalists cannot escape negative responses: “No one who tries to walk down the middle of a road during a firefight could possibly emerge unscathed.”33 Balance is a strategy by which journalists attempt to satisfy these audiences.34 As we will see, though, addressing a mobilized and dichotomized audience is not the only practical reason for balanced objectivi...