![]()

1 STATE, BUSINESS, AND REFORM

METHODOLOGICALLY SPEAKING, state-business relations as an object of study can be approached as both a cause and an effect. Although it is difficult to separate the two in practice, they can and should be distinguished analytically if we are to operationalize state-business collaboration. As an effect, or an outcome, the study of state-business relations involves the examination of the interactions of various macrolevel variables. This kind of examination can be carried out by drawing primarily on historical-institutional analysis and structural variables that shape the creation of networks. As a cause, the study of state-business relations aims to operationalize the nexus between state and business in order to determine its impact on economic change and developmental outcomes. Here the outcome to be explained is prolonged economic stagnation with costly developmental outcomes. The analysis proceeds by conceptualizing the category of “business” (for example, business as capital, network, sector, association) in respective contexts, in both time and space. In the Syrian case during the period under study, as in many developing countries with a similar level of development, “business” can be conceptualized as network, for it exhibits network-like structures rather than those of sectors, firms, or meaningful associations.1

As a causal factor, the study of state-business collaboration draws on more microlevel strategic analysis and choice theories that are bound up with rational choice and historical institutionalism. A fruitful explanatory and interpretive analysis would be one that dynamically integrates the study of state-business collaboration as both a cause and an effect; that is, it would examine the origins or causes of the interaction between the state and the business community, and then examine the effects of those interactions. This causal chain represents both the argument and the analytical map of this book, and explains the transformation of the business community in general across time. The starting point is the state of the Syrian economy, followed by the factors that help shape it.

THE STATE OF THE SYRIAN POLITICAL ECONOMY: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

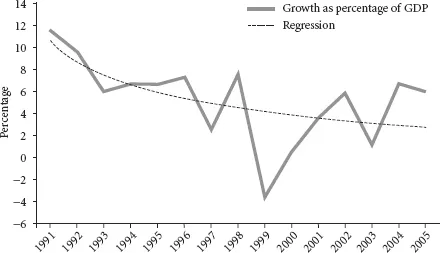

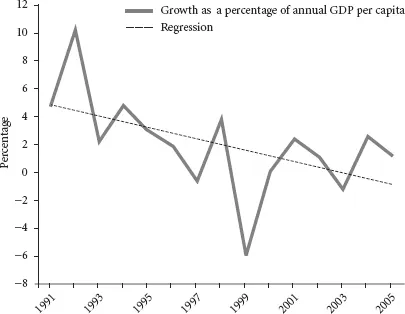

After a brief period of nominal economic growth in the early 1990s—financed largely by a consumption boom and erratic debt-for-commodities substitution schemes with the former Soviet Union and its immediate inheritors—signs of Syria’s decrepit economy began to surface. After peaking in 1992 and 1993, economic growth continued to decline until 2005 (see Figure 1.1). The available data from virtually all sources also denote a considerable decrease in GDP per capita, signaling not just economic trouble but also increasing socioeconomic disparity.2 After its decline in 1994, “GDP per capita growth” through 2005 never again reached 1994 levels (see Figure 1.2). Notwithstanding variables such as rain seasons and oil production, the dominance of privileged rent-seeking networks has contributed immensely to the direction and type of economic and developmental outcomes that obtained in Syria between 1986 and 2005.

Figure 1.1. Economic growth in Syria, 1991–2005. Data from Economist Intelligence Unit, “Syria Country Report,” 1991–2009.

The cracks in the façade spread after 1993 as the result of an inhospitable investment climate and tailored policies that marginalized competitive and production-oriented businesses in favor of protection for well-connected and service-oriented private ones. Invariably, the primary beneficiaries of protection and tailored policies were the same individuals and groups—in both the private and public sectors—who were benefiting from prior state-centered economic arrangements. What changed was the formalization of previously informal partnerships and relations between state officials and private business actors. In some cases, this involved the entry of numerous businessmen into public life through parliament and “subsidized”3 election onto the boards of Chambers of Commerce and Industry. More conspicuous was the formal entry of the regime elite and their offspring into the private sector on a large scale. These new “entrepreneurs” began to crowd out traditional businesses and businessmen, especially in the commercial and transportation sectors, in the mid- and late 1990s.4

Figure 1.2. GDP per capita growth, 1991–2005. Data from World Bank, World Development Indicators Database.

In the late 1990s, economic downturns persisted and collided with the broader political logic of the regime,5 one that subordinates economic rationality to security concerns, although not to the point where economic decline serves neither. It is as though the Syrian regime, by virtue of its exclusionary relations and practices, had hit an institutional dead end: it had lost much of its already modest ability to mobilize collectivities or discipline social sectors6 for the purpose of producing collective gains.7 Instead, the regime could exercise control only by limiting and constraining certain economic activities or, alternatively, by providing rent opportunities for allies—opportunities that did not bode well for the health of the economy as a whole.

The limits of economic change in Syria coincided with the limits of state-business collusion (that is, cronyism) as manifested by networks of capitalists and “bureaucrats.” After half a dozen years of stagnation, it took a succession crisis in June 2000 to shake the stalemate: immediately after the death of President Hafiz al-Asad, several prominent members of these networks were cast aside and many others were arrested or hassled under charges of corruption, such as the businessman and former parliamentarian Ma’moun al-Homsi.8 But such reshuffling had limited effects as it was also intended to consolidate the rule of the new leadership under Bashar al-Asad, a challenge that was accomplished in 2005 with the holding of the tenth Ba‘th Regional Command Conference. By 2001, the Syrian economy began to witness some change in the cornerstones of central economic planning at the macroeconomic level, including the financial sector. Bashar’s first ministerial shuffle brought new faces into key economic posts, and this new team undertook such tasks as overhauling the outdated state banking system, creating new, highly lucrative opportunities in the telecommunications sector, and expanding free trade zones around the country.9 The finance and banking sector in particular has seen a slew of ostensible liberalizations, beginning with the process of legalizing private banking in 2001—the first private banks opened in 2004, and the private banking sector has claimed 20 percent of the financial services market share in four short years.10 In 2005, the regime established the Syrian Stocks and Financial Markets Authority to oversee the Damascus Securities Exchange, which opened in March 2009. The first years of Bashar’s rule also saw the legalization of private currency exchange, lowering the financial barriers to trade. Midway into the first decade of Bashar’s rule, these developments mobilized the upper echelons of the private sector irrespective of their membership in privileged networks. In 2007, private sector interests banded together to form two holding companies—Cham Holding and Syria Holding11—which have since invested in a new domestic airline and pursued development projects alongside Gulf investors. During the same year, some of the same investors formed the Syrian Business Council, a new and self-proclaimed “modern” business association that looks after their interests while addressing the needs of a new, information- and communication-driven economy.12 Though such developments are beyond the confines of this study, they indicate the decline of privileged networks as the dominant route to economic “success” after 2005, and for good reason.

Regime-Business Mistrust

I argue that public-private networks emerged as a result of the state elite’s security concerns shortly after the 1970 coup, launched by the more pragmatic wing of the Ba‘th party, and led by then defense minister Hafiz al-Asad. By 1970, the helm of the Ba‘th regime was dominated by an increasingly rural-minoritarian leadership. This social stratum was embattled by the social and political struggles of the 1950s and 1960s, and was seeking both to moderate the politically unsustainable radicalism of the Ba‘th and to establish détente with the weakened but potentially destabilizing traditional sectors (primarily urban-Sunni sectors). Not lacking social historical roots, this adversarial legacy between a radicalized rural-minoritarian regime and a conservative urban-Sunni business community bred mistrust and antagonism between those who held power and those who held capital.13 At the same time, however, the two parties needed each other: state intervention in the economy required the cooperation of the private sector, or parts of it; and the disempowered business community was looking to rejuvenate itself. From the perspective of a quasi-socialist regime that places a premium on statist development and decisional autonomy, a formal incorporation of the entire business community was politically risky and untenable. Alternative forms of incorporation had to be sought.

On the eve of the 1970 coup, state-business antagonism and mistrust were already a deep-seated legacy. Initially, this legacy prevented Hafiz al-Asad’s regime from dealing formally with the business community as a whole, and from legitimizing the role of the private sector. Unable to discipline the private sector as a whole, the Syrian regime resorted to the creation of informal ties with particular members of the existing business community, some of whom acted as the unofficial partners of state elites (later called the “state bourgeoisie”). Thus, in contrast to the post-Nasir Egyptian regime, the Syrian regime opted for maintaining its principal cornerstone, a weakened Ba‘th party, and replacing a politicized army with a massively refurbished security apparatus that constituted a strong backbone for public-private ties. Emerging state-business networks served as an alternative agency for capital accumulation and, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as an alternative support base during times of political crisis—particularly when the Muslim Brotherhood sought to undermine the authority of the regime.14

Over time, these informal webs of state-business ties formed and reformed rent-seeking networks that developed a life of their own, as demonstrated by their impact on economic change after 1986, as the regime attempted to handle a major economic crisis. This was even more evident after 1991, when these networks became the basis of the official institutional expression of the private sector. Nonetheless, most changes in economic policy after 1986, including the active resistance to change in some economic policy areas, can be traced back to the influence of these economic networks rather than to either the aspirations of the business community as a whole or the statist logic that guided economic policy until 1986.

Oil and Strategic Rents

At the macroeconomic level, the policies promoted by state-business networks involved massive misallocation of resources and a lack of comprehensive vision for reform and constitute...