![]()

PART I

PAINTING IN THEORY

![]()

FIRST MOMENT

HEGEL’S AESTHETICS

KANDINSKY DECLARED the fundamentally Hegelian nature of his views in the very first lines of Über das Geistige, its opening phrase—“Every work of art is the child of its time”—having been lifted almost verbatim from the Aesthetics.1 In fact, Kandinsky’s entire first paragraph reads largely as a précis of a key passage in Hegel—though, significantly, one that appears at the end of the Aesthetics’s historical narrative, in the section that lays out the dissolution of the romantic arts, and so the decline of art tout court. Here is the relevant passage from Hegel:

Now just as every man is a child of his time in every activity, whether political, religious, or scientific, and just as he has the task of bringing out the essential content and the therefore necessary form of that time, so it is the vocation of art to find for the spirit of a people the artistic expression corresponding to it. Now so long as the artist is bound up with the specific character of such a world-view and religion, in immediate identity with it and with firm faith in it, so long is he genuinely in earnest with this material and its representation . . . only in that event is the artist completely inspired by his material and its presentation; and his inventions are no product of caprice, they originate in him, out of him, out of his substantial ground, this stock, this content of which is not at rest until through the artist it acquires an individual shape adequate to its inner essence. If, on the other hand, we nowadays propose to make the subject of a statue or painting a Greek god, or, Protestants as we are today, the Virgin Mary, we are not seriously in earnest with this material. It is the innermost faith that we lack here.2

Although Kandinsky simplified both the Aesthetics’s grammar and its argument, Hegel’s basic claims persist:

Every work of art is the child of its time, often it is the mother of our emotions. Thus, every period of culture produces its own art, which can never be repeated. Any attempt to give new life to the artistic principles of the past can at best only result in a work of art that resembles a stillborn child. For example, it is impossible for our inner lives, our feelings, to be like those of the ancient Greeks. Efforts, therefore, to apply Greek principles, e.g., to sculpture, can only produce forms similar to those employed by the Greeks, resulting in a work that remains soulless for all time.3

Kandinsky’s decision to begin his text with a passage drawn from the end of the Aesthetics might easily be seen as part of a larger effort to reopen the latter’s closure and thereby revise its historical trajectory. Certainly it was the ending of Hegel’s narrative that posed the greatest challenge to artists of Kandinsky’s generation. In order to understand why Hegel saw it as the necessary conclusion to his story, and also how Kandinsky might have seen things otherwise, we will need to sketch out the general shape and sweep of the Aesthetics’s highly nuanced history of art. It would also be useful to review, however briefly, the structure of Hegel’s larger philosophical system, so as to better grasp the crucial but limited place that art occupies within it.

The idea of spirit (Geist) is the central motif of both the Aesthetics and the Hegelian system at large. By “spirit,” Hegel intended a collective human subjectivity or consciousness, whose development over time could be seen to account for all significant—his phrase is “world-historical”—political, religious, intellectual, and artistic change. The 1807 Phenomenology of Spirit was the first of Hegel’s books to try to describe at least a portion of the circuitous route that spirit had traveled on its path to the present. The text has therefore occasionally been regarded as a sort of Bildungsroman, recounting the growth and maturation of its protagonist over the course and as a result of its various, frequently harrowing experiences. Indeed, that latter term, experience (Erfahrung), is also an important one for Hegel, and is intimately bound up with his conception of the dialectical structure of history. As Frederick Beiser explains,

Hegel is . . . reviving the original sense of the term, according to which ‘Erfahrung’ is anything one learns through experiment, through trial and error, or through en-quiry about what appears to be the case. . . . [It] is therefore to be taken in its literal meaning: a journey or adventure (fahren), which arrives at a result (er-fahren), so that ‘Erfahrung’ is quite literally ‘das Ergebnis des Fahrens.’ The journey undertaken by consciousness [or spirit] in the Phenomenology is that of its own dialectic, and what it lives through as a result of this dialectic is its experience.4

Crucial to Hegel’s conception of experience is his assertion that spirit never ends its journey in quite the same state or place from which it set off. The dialectic entails a movement outside into otherness, followed by reflection, and then a “return” to a self that has been substantially changed through the process. Of the several means by which spirit has externalized or stepped outside itself, art, according to Hegel, was initially the most important.5 Historically, works of art were above all a way that spirit took sensuous, material form, and so brought itself before itself, for the specific purpose of its conscious self-reflection. Humanity’s increasing self-awareness—and more, its realization of freedom—has come in no small measure, Hegel says, through the experience of art.

The freedom at issue here is principally a freedom from nature’s determinacy.6 In the Aesthetics, Hegel argues that the earliest works of art gave form to a consciousness or spirit that was still trying to extricate itself from its subservience to nature, and so was not to be fully reconciled with sensuous materiality. As yet vague and undeveloped, with no sense of its own autonomy, spirit could express itself only indirectly; works of art could do nothing more than point to their spiritual content through their obdurate material form. This is presumably what Hegel has in mind when he refers to art’s earliest period as symbolic,7 and designates architecture as its predominant and most characteristic form. Hegel argues that the material used in these early works was inherently non-spiritual—mostly heavy stone whose shape was limited by the law of gravity—and that whatever meaning the works themselves may have had was carried by, or in some cases merely stamped onto, their external surfaces (see Figure 1).8

FIGURE 1. Temple of Amen-Re, Karnak, Egypt, Dynasty XIX, ca. 1290–1224 BCE. © 2013 Robert Harding Picture Library Ltd.

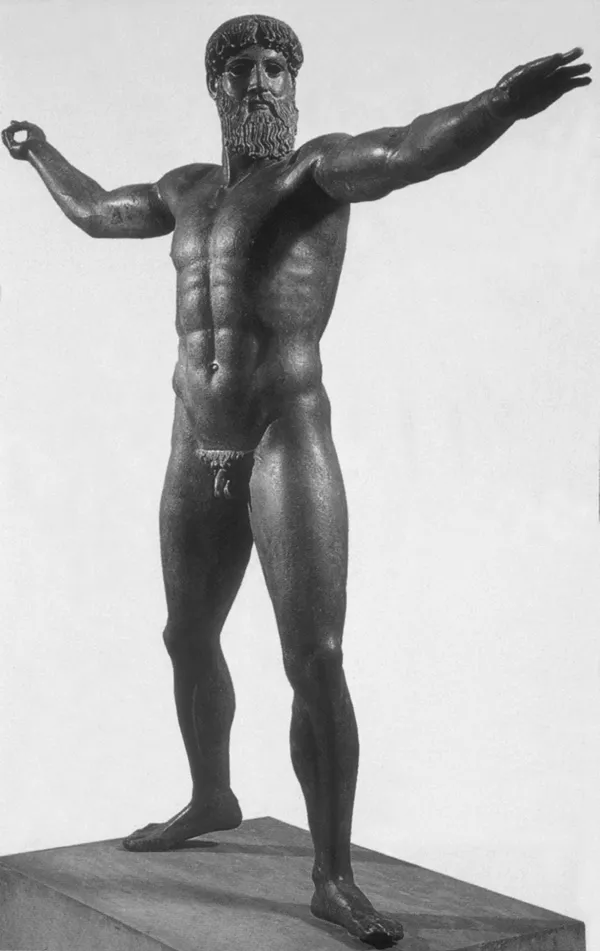

During the ensuing classical period, by contrast, sculpture became the predominant form of art. Classical sculptures were still produced out of heavy matter, of course, but now with little regard for its weight and natural properties (Figure 2). Each work’s form was determined solely by its chosen subject matter, which in this period, Hegel observes, was almost always the human form. The Aesthetics emphasizes that the cultural beliefs of ancient Greece were perfectly suited to sensuous embodiment—witness the anthropomorphism of its gods—so that the figures of classical Greek sculpture seemed thoroughly pervaded by spirit, their form and content fused in an indissoluble unity. In this sense the classical work of art didn’t so much mean (in the way that either a sign or symbol might) as simply exist: a pure self-showing.

FIGURE 2. Artemision Zeus, ca. 460 BCE. Bronze, approx. 6′10″ high. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. © Jack Balcer Image Archive, Ohio State University.

Yet the introduction of subjectivity into both the content of the work and the form of its presentation signaled the demise of the classical era. According to Hegel, in the ensuing romantic period, which arose with the advent of Christianity, spirit came to be characterized by a profound and ever-growing inwardness that, unlike the spirituality of the ancient Greeks, was only imperfectly expressed in the sensuous externality of art. Clearly sculpture was no longer up to the task, as it was unable to present consciousness as something withdrawn out of the sphere of material embodiment into self-reflection. It was instead in the painting of the romantic era (Figure 3) that inner subjectivity first found its adequate expression. Painting accomplished this by presenting its subjects in an artificial or “unnatural” space, one that had been created by subjectivity itself, for the purpose of its own self-contemplation. This was the space of visual illusion—the term Hegel uses is Schein—and it effectively dissolved the sense that what one beheld in the work was something objective, independent, and solidly material.

The work of sculpture has to retain [its independence] because its content is what it is, within and without, self-reposing, self-complete, and objective. Whereas in painting the content is subjectivity, more precisely the inner life inwardly particularized, and for this very reason the separation in the work of art between its subject and the spectator must emerge and yet must immediately be dissipated because, by displaying what is subjective, the work, in its whole mode of presentation, reveals its purpose as existing not independently on its own account but for subjective apprehension, for the spectator. The spectator is, as it were, in it from the beginning . . . and the work exists only for this fixed point, i.e. for the individual apprehending it.9

In its presentation of a space that was only apparently three-dimensional—that existed only through and for human consciousness—romantic painting was to be seen, Hegel argued, as a direct manifestation of spirit’s increasing inwardness and autonomy. Painting’s illusionistic space was one, moreover, in which human drama could unfold, and during the romantic era gesture and facial expression—along with other means for suggesting the interior life of the figures portrayed—were similarly perfected over time (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 3. Jan van Eyck, Madonna with Canon van der Paele, 1436. Oil and tempera on wood, 122.1 × 157.8 cm. Groeninge Museum, Bruges. The Art Archive at Art Resource, New York.

The romantic era differed from its predecessors, however, in that no single art form could be seen to predominate over its entire duration. At a certain moment, as Hegel tells it, spirit achieved a state of subjective inwardness no longer suited to even the most subtle of paintings, at which point first music and then poetry (with their still greater immateriality) rose to prominence among the arts. Already with the romantic era, then, we witness the dissolution, and so the beginning of the end, of art. Not that buildings, sculptures, paintings, musical compositions, and poems wouldn’t continue to be produced. They would, but they would no longer function as the primary vehicle of spirit—which is to say that they would no longer serve as the place where humanity realized its deepest and most meaningful truths. That role was given over first to religion and finally to philosophy, from whose vantage point it could be seen that the history of art belonged not, ultimately, to art itself; instead it constituted only a moment (now passed) within the larger history of spirit.

FIGURE 4. Rembrandt van Rijn, Syndics of the Cloth Guild, 1662. Oil on canvas, 185 × 274 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. bpk, Berlin / Rijksmuseum Amsterdam / Hermann Buresch / Art Resource, New York.

Because the story the Aesthetics has to tell is not in the end its own, it doesn’t follow the same dialectical structure of other Hegelian narratives.10 In both the Phenomenology of Spirit and the Science of Logic, for example, thought is seen to progress through three interrelated stages: from the universal (characterized by an inchoate unity), to the particular (in which energies are directed toward the differentiation of parts), and finally to an integration of those two earlier moments in a concrete individuality able to comprehend not only the whole but also the place of the parts within it. If the larger movement from art through religion to philosophy generally follows this pattern, the specifically art-historical narrative of the Aesthetics does not. We are instead presented with an inverted dialectic, an “unhappy” turn of events: art reaches its apex in the second (classical) moment, and then ends its story in the dispersion of its particular forms. The task of gathering those pieces together and reintegrating them into a meaningful whole is left to philosophy—more precisely, to the comprehensive system that Hegel himself articulated in the Aesthetics and elsewhere.

![]()

SECOND MOMENT [PART 1]

KANDINSKY’S ÜBER DAS GEISTIGE IN DER KUNST

ÜBER DAS GEISTIGE IN DER KUNST is aimed above all at restoring a properly progressive shape to the dialectic of art’s history, so as to assert the continuing relevance of painting and the other romantic arts. Admittedly, Kandinsky doesn’t use exactly those terms. We hear nothing of the “rom...