![]()

1 From Global to Local

CHINESE MIGRATION NETWORKS INTO THE AMERICAS

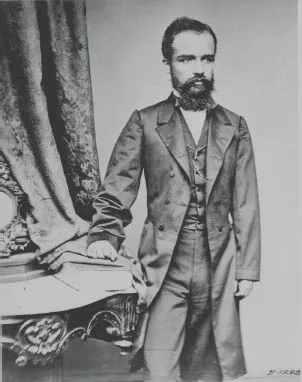

There was nothing in the lofty diplomatic career of Matías Romero to suggest that he would become a tireless advocate of Chinese immigration to Mexico (see Figure 1.1). Romero, a lawyer by training, joined the Liberal Party of Benito Juárez during the War of the Reform (1857–1861), when the influence of military leaders and the power of the Roman Catholic Church were replaced with a constitution-based civil society. In this period, Romero quickly climbed Mexico’s diplomatic ranks.1 At twenty-five years of age, the Oaxaca native had already served as Mexico’s chargé d’affaires and minister to the United States, where he tenaciously lobbied the Lincoln administration to arbitrate the French Intervention, in which France had invaded Mexico in 1862 under the leadership of Napoleon III. A dauntless proponent of liberalism, Romero facilitated U.S. investment in Mexico, earned the respect of Lincoln’s secretary of state, William H. Seward, and engendered a close friendship with General Ulysses S. Grant. Romero proved equally effective as secretary of the treasury, offering, among many suggestions, that the United States assist Mexico in settling its debts with Britain, France, and Spain.2

Neither Romero’s extensive diplomatic résumé nor his trust in free-market solutions inspired the young attaché to turn to Chinese labor. In fact, Romero’s plan transpired from his own frustration with growing coffee in Soconusco, Chiapas, which he pursued after poor health steered him temporarily away from politics in 1872. In his estimation, the tierra caliente, Mexico’s tropical hotlands abutting Guatemala and Belize, held immense potential, but the region lacked a steady workforce to make coffee profitable. After all, Romero’s ambition was not to provide Mexicans with the rich, aromatic drink, but to supply Americans with high-quality coffee beans, produced from the drudgery of Chinese laborers.

When Romero returned to politics as senator of Chiapas in 1875, he conveyed his plans in two essays that were circulated in Mexico City-based newspapers: Revista Universal and El Correo del Comercio. Romero’s writings were consistently optimistic, appealing to the popular belief that where Chinese toiled in cane and cotton fields and filled mining and railroad camps, progress occurred. The former coffee grower stirred optimism that development was possible even in the most remote, most arid parts of the world. “It seems to me,” he surmised, “that the only colonists who could establish themselves or work on our coasts are Asians, primarily from climates similar to ours, primarily China. . . . This is not an idle dream. Chinese immigration has been going on for years, and wherever it has occurred prudently, the results have been favorable.”3 Enamored with China, Romero also added Japan to the mix of countries from which Mexico stood to benefit as a source for immigrant laborers.4

FIGURE 1.1 Portrait of Matías Romero, 1863. Image presented to the U.S.Government in 1863/Civil War Series. http://www.civil-war.net/cw_images/files/images/184.webp

If Romero’s vision represented one possible pathway to modernity, it did so within a global context, one rich in international migration amid competing imperial and national worlds. Within this uncertain landscape, Romero pursued his conviction that the solution to Mexico’s labor shortage lay across the Pacific Ocean. In 1882, an appointment as Mexico’s minister plenipotentiary under the presidency of Porfirio Díaz finally afforded the physically fragile but politically stalwart public servant the influence to promote Chinese immigration.

Vigorous discussion ensued between Romero and a range of Qing Dynasty officials. Diplomats traded gifts: chocolate, rope from the fibers of the henequen plant, and Veracruz coffee beans in exchange for porcelain vases, tea, and cloth made from hemp.5 Eventually, Chinese laborers arrived in Mexico under official treaty protection, but not until 1899, twenty-four years after Romero first advocated for such immigration, and one year after the intrepid politician succumbed to an appendicitis attack.6 The delay in China-Mexico diplomacy was in no way due to a lack of effort or forethought on the part of Romero, who had distinguished himself as an astute observer of the mid-nineteenth-century world. The tireless immigration advocate could never, however, have anticipated the dynamic of overlapping empire-states and nation-states that would both produce and delay the very scope and manner of the arrival of Chinese into Mexico and its borderlands with the United States.

Opium Networks and Imperial Unrest

The complexities bearing on Romero’s pursuit of opening up Mexico to Chinese immigration were a reaction to and emblematic of sweeping transformations occurring at the global, national, and local levels in the Pacific world at that time. Within South China and on its adjacent seas, the trading of British commodities and Spanish silver for South Asian opium established durable systems of illegal drug trafficking in the early nineteenth century. Decades later, these systems would evolve into trans-Pacific migration networks to facilitate the labor needs of transitioning imperial and national economies. After the 1820s, as Chinese, British, and American smugglers solidified mutually trusting relationships, the opium trade developed into a tightly organized cartel, the strength of which lay in the structure of its business alliances. To move the drug efficiently and into local and international markets, small, independent opium syndicates formed strong connections with experienced ship captains, who in turn hired large crews of men to help transship opium. The highly organized network also relied on the latest innovations in maritime communication and shipping technology, which made the smuggling of opium from India to South China and into Western markets remarkably efficient. Schooners arrived from Bengal at Kumsing Moon off the coast of Macao in May or June to transfer chests of “black-earth,” “white-skin,” and “red-skin” opium to Chinese intermediaries.7 Opium merchants then made their way into South China’s inner harbors by collaborating with local sailors, who transported opium to their customers through the meandrous and narrow Canton Delta region using agile sampan ships. By late October, the selling and distribution of opium was complete. Schooners anchored at the harbor of Lintin, an island just north of Hong Kong, until late spring of the following year, when merchants and smugglers followed the same seasonal routine to acquire and sell opium.

Heu Kew, a subcensor in the Qing Military Department, described in frustration the scheming of opium cartels, which he was powerless to break: “The traitorous natives who sell the opium cannot altogether carry on the traffic with the foreign ships in their own persons. To purchase wholesale, there are brokers. To arrange the transactions, there are the Hong merchants. To take money and give orders to be carried to the receiving ships, that from them the drug may be obtained, there are resident barbarians. . . . And to ply to and fro for its conveyance, there are boats called ‘fast-crabs.’”8 Within the taut, highly efficient organization of the trade, annual importations in opium rose gradually from two thousand chests in 1800, five thousand in 1820, and sixteen thousand in 1830, to twenty thousand chests in 1838.9

The robust trading networks impressed many, especially those who were profiting from the cartel, but the durability and forcefulness came at a high cost. The strength of the opium networks sowed deep enmity between Chinese natives and British interlopers. Choo Tsun, a member of the council of the Board of Rites, expressed a common viewpoint: “The natives of this place were at first . . . active. . . . But the people called Hung-maou [red-haired], came thither and . . . in introducing opium into this country, their purpose has been to weaken and enfeeble the Central Empire.”10 Repeated bans, the burning of pyres of opium, and harsh penalties for merchants, smugglers, and users failed to end the trade. Whereas the interests of opium smugglers demanded bonds of common trust, the Qing and British officials harbored deep misgivings for one another. For lack of a diplomatic tradition on which to draw and for want of a middle ground on which to meet, the far-reaching evils of opium led to war, and the status quo in China gave way to British imperialism.

The spoils of the First Opium War, as codified in the Treaty of Nanking (1842), bestowed British control over the ports of Canton (Guangzhou), Amoy (Xiamen), Fuzhou (Foochow), Ningbo, and Shanghai, and later eleven others, including Shantou (Swatow) and Qiongshan.11 The dealings of the British Empire with the Qing Dynasty proceeded from the conviction that the so-called treaty ports were, and should remain, bastions of unencumbered global exchange in order to benefit the Crown directly and the United States, Portugal, the Netherlands, Russia, France, and China obliquely (see Map 1.1). After the First Opium War in 1842, the emer gence of Hong Kong and Canton as British-controlled treaty ports shifted commerce firmly into South China. Markets gradually reoriented southward from Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Wenzhou, while contraband trade in opium continued unabated.12

MAP 1.1 China Treaty Ports and South China. Drawn by Erin Greb.

Aside from a small number of merchants who applied their management skills from the opium trade to emigration brokering, few Chinese benefited from the new economic configuration. Dislocation and poverty caused by continuous war and village strife constrained the lives of most Chinese. Hong Kong, which was ceded to the British Crown in 1842, quickly acquired a reputation for unfettered commerce and as a hub for opium trafficking.13 The colony’s 21,514 inhabitants—mostly native Chinese and British merchants and their families—seemed well equipped to handle the turbulence of legal and illegal market exchange, until British and Qing authorities called Hong Kong’s status as a duty-free zone into question. With piracy going nearly unchecked in and around the colony, legal trade languished while illicit exchange in opium flourished.

In nearby Canton, the opposite blueprint emerged. Merchants from around the globe descended on the Guangdong capital city to trade and receive goods, paying duties on both imported and exported items. Hongs—Chinese franchised merchants licensed by the Qing emperor to trade with Westerners—mixed and competed with the thirteen European and American commercial houses on China Street. As foreigners and hongs prospered, Chinese boat merchants suffered the inequities of the new trade regime, and some fell into medicating themselves with “poisonous liquors” in the hovels of adjacent Hog Lane.14

The terms of trade positioned the British Empire quite favorably in South China. British envoys worked alongside Qing customs officials to collect duties on imports and exports and to tender fines on wayward merchants. But as relations among Qing and British imperial authorities edged tentatively toward conciliation, efforts at accommodating post-war labor demands brought to bear old tensions from within and introduced fresh problems from without. Overpopulation, the shift to commercial agriculture, and export manufacturing displaced subsistence farmers from traditional landholdings. Cheaper British textiles drove Chinese clothmakers out of business, while many porters and warehouse employees lost their jobs when new treaty ports opened to export exchange.15

Ethnic violence and civil war exacerbated the changing economic regime in South China. Commencing in 1851, the Taiping Rebellion claimed more than twenty million lives by 1864, when Qing forces quashed the advocates of the “Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace.”16 During the same period, the so-called Red Turban Rebellion divided loyalties between the Qing and anti-dynastic Triad organizations in the Canton region.17 More than one million Chinese lost their lives in battle, while the Qing army executed an additional seventy thousand Red Turban sympathizers. To make matters worse, ethnic tensions between the Hakka minority and the Punti majority plagued the Guangdong districts of Xinhui, Taishan, Kaiping, and Enping, known collectively as Siyi or the Four Districts. In 1855, Hakka claims to scarce arable lands set off a twelve-year clan war with Siyi residents, and thousands more Chinese died.18 British imperial control, ethnic violence, and the durability of the opium trade combined to create a national landscape in which migration became an ever-greater probability. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese would take up this path, voluntarily or not.

Between Slavery and Freedom: Migration Networks and Coolieism

The collision of the British Empire and the Qing Dynasty yielded to new arrangements of power that remade South China into a locus of transoceanic migration. The forces of rapidly shifting empire-states and nation-states and their transitioning economies configured transoceanic networks that were initially created from the early to mid-nineteenth century opium trade. In a little less than a decade, opium transportation networks matured to accommodate both the imperial appetite for semi-free labor and the demand for wage labor on the part of nation-states. A...