![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

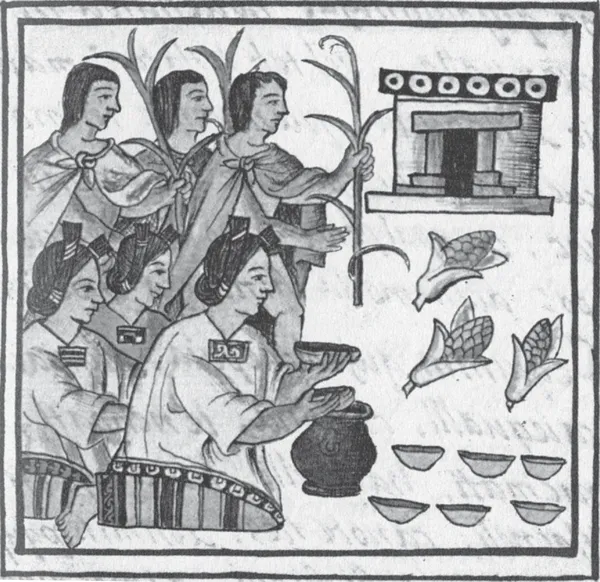

When illustrating the offerings that Nahuas made to the goddess Chicome Coatl at her temple at Cinteopan, the indigenous artist beautifully rendered the complementary and interdependent relations of men and women (see Figure 1.1). His drawing shows young men presenting corn stalks, representing their agricultural labor, and young women carrying atole (a corn beverage), symbolizing their responsibility for preparing food and drink. The gifts highlight men’s and women’s gender duties and mutual obligations to their households, communities, and deities. The distinctive clothing and hairstyles mark their gender, age, and status. The location of the women in the lower register of the image, seated, and of men in the upper register, standing, corresponds to native cosmologies in which the earth (lower) is conceived of as female and the sky (upper) as male. The balanced composition of the image and the symmetry in the presence and number of men and women reveal the parallel and complementary organizing principles of indigenous social and gender relations.

Archival narratives from colonial Mexico both confirm and contradict the idealized view of gender relations in the ritual depicted in the temple of Cinteopan. The rich historical record in Mexico reveals a broad range of Mesoamerican women’s daily activities, which were vital to the social, economic, and spiritual life of the community. As tribute-paying commoners, they can be seen spinning yarn, weaving cloth, grinding corn, making tortillas, and providing service in the homes and on the lands of native elites and Spaniards. They emerge as market vendors, some with significant investments in native and Spanish goods. Many women appear as property owners, who inherited and bequeathed lands and belongings. They stand out as wives who, if necessary, tried to force their husbands to fulfill marital obligations. Some even appear as legitimate native rulers, or cacicas, of their local states. Other indigenous women confronted and fought with outsiders to protect the people and resources of their communities throughout central and southern Mexico. And yet so many of their stories are unknown to us and remain to be told.

This book offers a social and cultural history of indigenous gender relations in colonial Mexico from these many different perspectives, beginning with the Spanish conquest in the 1520s and ending in the first half of the eighteenth century. I examine cross-cultural patterns in women’s roles and status, focusing primarily on four native groups in highland Mexico: the Nahua people of central Mexico, who spoke Nahuatl; the Ñudzahui (Mixtec) people of the Mixteca Alta in northwestern Oaxaca; and the Bènizàa (Zapotec) and Ayuuk (Mixe) peoples of the Sierra Zapoteca in eastern Oaxaca. I do not claim to address the histories of all indigenous groups in highland Mexico. I do not include the Maya of Yucatan, Chiapas, and Guatemala, or the many other culture and language groups of Mesoamerica, such as the Otomi. Nonetheless, at the time of the conquest, the groups that are the focus of the study—the Nahua, Ñudzahui, Bènizàa, and Ayuuk—were among the most populous, sedentary civilizations in Mesoamerica, and they shared countless defining social, cultural, and political traits, despite differences in language and sociopolitical organization. The peoples of highland Mexico also shared a common history under colonial rule. In the first two or three generations after the conquest, the Spaniards introduced far-reaching changes in native communities by establishing town councils, parishes, and a new tribute system, and by bringing a new material culture, domesticated animals, and diseases. Much of this history of native women and men under colonial rule considers, on the one hand, pragmatic acceptance, adoption, and adaptation of Spanish institutions, concepts, and practices and, on the other hand, rejection and resistance that has often been overlooked.

Figure 1.1. Offerings to the goddess Chicome Coatl at Cinteopan revealing the gendered division of labor in Nahua society

SOURCE: Florentine Codex, bk. 2, fol. 28. Florence: Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Med. Palat. 218, c. 82. By concession of the Ministry for Heritage and Cultural Activities; further reproduction by any means is forbidden.

The broad geographical and temporal scope of this study enables me to trace similarities and differences in women’s roles and status among some of the major culture groups of central Mexico and Oaxaca.1 The long period from 1520 to 1750 corresponds to the periodization of several important works on native society and culture at the corporate level. Furthermore, with some notable exceptions, much of the recent scholarship on Mexican women has focused on either the postclassic period (pre-1519) or the late colonial (post-1750) and Independence (1810–1820s) periods, leaving the first two centuries of colonial rule to a handful of scholars.2 This work seeks to help fill in this gap.

In writing this book, I have five principal objectives. First, I seek to contribute to Mesoamerican women’s history by considering indigenous women from across the social spectrum, both commoners and elites, especially in rural communities where most indigenous people lived in this period. The existing scholarship on gender in the colonial period focuses overwhelmingly on Spanish and casta (racially mixed-heritage) women’s status in the family and marriage, and especially on elite urban women.3 Despite their very significant contributions to the study of women, these works examine women’s status within a framework of Spanish custom and morality and do not specifically address indigenous gender relations. For some groups, including the Bènizàa and the Ayuuk, little or nothing has been written on indigenous women’s lives under colonial rule. This book breaks new ground by integrating their experiences into a broader discussion of gender relations in central Mexico and Oaxaca. My focus on women does not overlook the fact that women’s status must be considered in relation to men’s. In fact, the historical record confirms that the household was the basic social unit in which men and women lived their lives as partners much more so than as individuals.

Second, I examine the formation and expression of gender identity in highland Mexico. I show how a binary gender system was imposed through roles, rituals, and behavior as a way to order and streamline the more complex realities of gender ambiguity, instability of the body, and variation in personal traits. I consider how concepts of femininity and masculinity influenced the idealized roles of women and men, and how gender ideology was tied to social, political, and economic power. I consider how gender dynamics shaped interactions in the household and community and among indigenous peoples and other ethnic groups.

Third, I place social relations in the household at the center of analysis. In doing so, I seek to shift the focus away from colonial institutions, such as the cabildo (municipal council), and predominately male actors, both Spanish and indigenous, in order to better understand the contributions that women made to their societies and cultures and to provide a more intimate, internal view of communities.

Fourth, I consider the impact of Spanish institutions, social customs, and cultural attitudes on indigenous gender relations and women’s status. I am especially interested in how Christianity, monogamous marriage, patriarchal gender attitudes, the colonial tribute system, and legal culture, for example, altered social relations in communities. Spaniards, mestizos, and Africans are not as prominent in this study, reflecting the milieus that I encountered in the sources, which originated mainly in native communities. Nonetheless, this investigation considers the presence and influence of nonindigenous people in cabeceras (head towns) and nearby cities, and thus sheds light on interethnic relations and interactions in New Spain.

Fifth, I show how understanding indigenous women’s history is vital to our understanding of the early modern Atlantic World. Aside from Malinche and Pocahontas, native women are rarely mentioned in narratives on the colonial encounter and the development of new societies in the Americas. Many scholars have not fully appreciated the fact that indigenous women and men produced the wealth in Mexico (and many other places) that stimulated further European expansion, settlement, and immigration; financed the early African slave trade; and established the patterns of economic production based on the exploitation of cheap labor and the extraction of natural resources that were key components of the emerging Atlantic World.

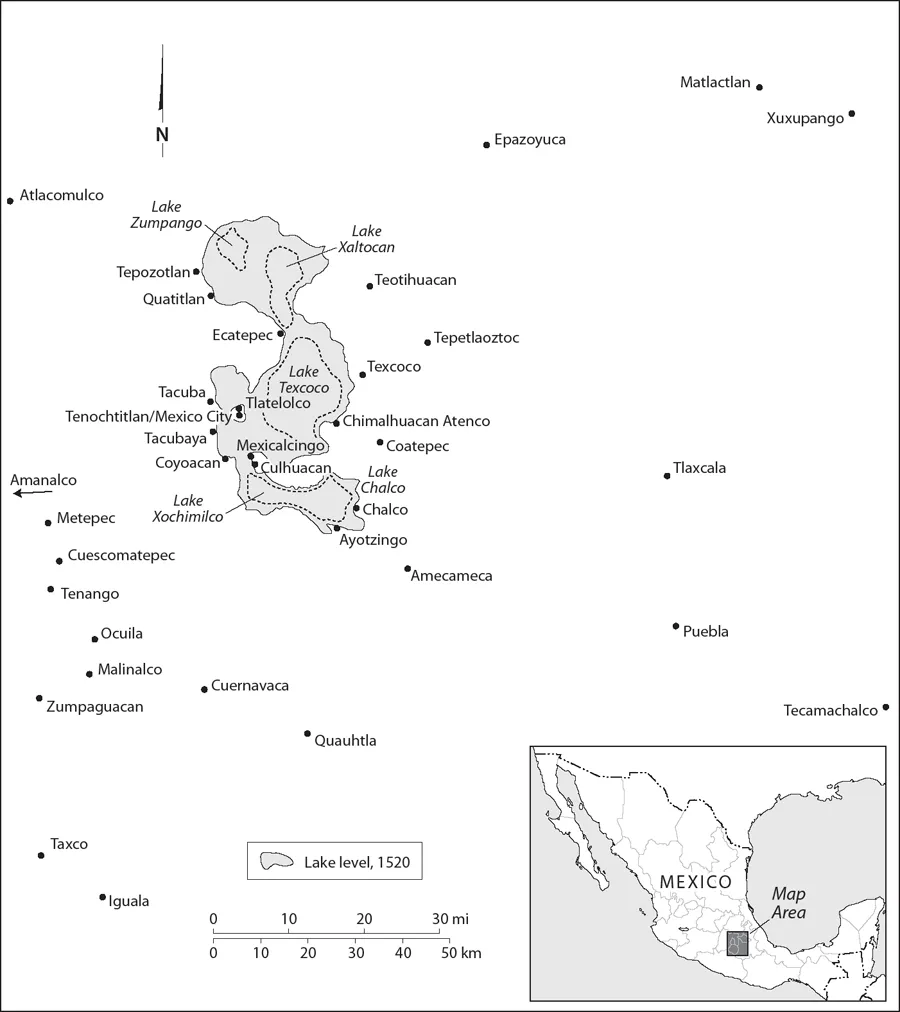

This study draws on a rich collection of archival, textual, and pictorial sources to identify and trace changes in women’s economic, political, and social status in colonial native societies and to consider the extent to which Spanish gender and sexual ideologies influenced native attitudes and practices in the first several generations after contact. These sources represent more than a hundred communities in central and southern Mexico (see Maps 1.1 and 1.2). The records were written in native languages (mainly Nahuatl and, to a lesser extent, Tíchazàa and Ñudzahui) and in Spanish. Native-language sources reveal categories and concepts that are often obscured by Spanish or English translations and therefore are critical to this study. Whenever possible, I have tried to use documents generated by indigenous peoples themselves rather than rely on the commentaries of Spanish observers. My sources include indigenous- and Spanish-language formal texts and speeches, confessional manuals, doctrinas, grammars, criminal records, last wills and testaments, land documents, inquisitorial proceedings, late sixteenth-century questionnaires (Relaciones geográficas), and pictorial writings. Many of the texts, although written after the conquest, refer to ancient traditions, society, and history, contributing a wealth of information on the postclassic and early colonial periods.

Map 1.2. Mixteca Alta and Sierra Zapoteca regions of Oaxaca

Most of the sources used in this study, however, were written at least two generations after the conquest and so reflect some degree of Spanish influence. After the initial decades of contact, most indigenous people of highland Mexico operated in a native-Christian context, often making it difficult to distinguish between Spanish-Christian and native ideals. Still, in most cases the community remained the locale of indigenous cultural practices and Mesoamericans vastly outnumbered Spaniards outside of cities, especially in southern Mexico. Therefore we can reasonably observe many indigenous patterns in the record that reflect native concepts and practices, particularly in regions where few Spaniards settled. Changes in ideology and social relations are less pronounced than changes in native governing institutions. I argue that it is possible to identify and trace patterns in indigenous gender relations and ideologies across the colonial period, aware that native cultures and value systems responded to dynamic, complex processes of change. Indeed, the same ideals and morals that were affirmed in formal speeches and life-cycle rituals were contested in household conflicts and disputes mediated by native and/or Spanish officials.

Since all the sources from this period were written by men, male perspectives color commentaries on society and gender in New Spain. Nevertheless, by reading these accounts critically, we can use them to reconstruct in part the roles and status of women. Even when shaped by colonial legal formulas, careful reading of the documents sheds light on gender relations and women’s legal and economic status. Women’s voices can be recovered in testaments, petitions, and testimonies from a variety of archival collections.4 Although we might expect that women in this period appealed to the patriarchal ideology of Spanish magistrates and priests, we see many examples of their assertion of gender rights and articulation of marital expectations that did not conform to the attitudes of colonial elites. I use thousands of observations drawn from incidental information, especially from criminal records, to discern patterns of labor, social networks, and gender dynamics. I have tried as much as possible to integrate these voices and insights into the text by using abundant examples and quotes.

The book’s title, The Woman Who Turned Into a Jaguar, is derived from a Zapotec man’s 1684 court testimony in which he tried to justify his assault on his wife that led to her death. His captivating tale of the nahualli (a person who has the ability to transform into an animal) transformation of his wife, discussed in Chapter 2, exemplifies the many types of surprises that historians find in the colonial record. It also reveals the persistence of indigenous concepts and practices one hundred and fifty years after the Spanish invasion and how documents generated in colonial courts can diverge significantly from legal formulas and the calculated strategies of Spanish lawyers. In this case, the Zapotec man’s testimony elicited scorn and skepticism from the Spanish judge, revealing a clash of worldviews between indigenous community members and colonial authorities that appears time and time again in the colonial record. Finally, the story offers a reminder that the perspectives of witnesses and authors shape testimonies, statements, and texts in the colonial archive.

Competing narratives in the historical record articulate different perspectives that confirm and contradict, complement and complicate, formal texts and prescriptions of gender roles and behavior. Many previous studies of native women in preconquest and colonial Mexico have turned first and foremost to prescriptive texts, such as speeches in the Florentine Codex; some do not venture far beyond these sources in their analysis. Such texts represent conservative, idealized roles that fail to provide a comprehensive view of women’s activities, and yet they still reveal values essential to reconstructing aspects of native ideology. Preconquest and colonial pictorial manuscripts provide another dimension to topics represented in the many genres of alphabetic writings.5 By reading a wide variety of sources, I have exposed certain biases and filled in gaps left by other records. Thus, archival documents, formal texts, and images, when read against each other, shed light on a range of views and conflicting perspectives of gender rights and obligations. The use of many different source types allows me to consider multiple criteria in the analysis of gender relations. I liken my methodology of integrating fragments of information from different perspectives to a woman’s work of spinning thread and weaving cloth. The sources are the raw materials, which I sort and spin into threads of evidence, and then weave into patterns that tell a coherent, complex story of indigenous women’s lives.6

This project has been informed by historiographical developments in two veins of colonial Mexican scholarship: women’s history and ethnohistory. Ethnohistorical, and especially indigenous-language based, studies have emphasized the complexity and diversity of Mesoamerican culture before and after the conquest and have revealed the many forms of adaptation that indigen...