![]()

1

Death in Transition

Reclaiming the (Un)known Dead in Postconflict Peru

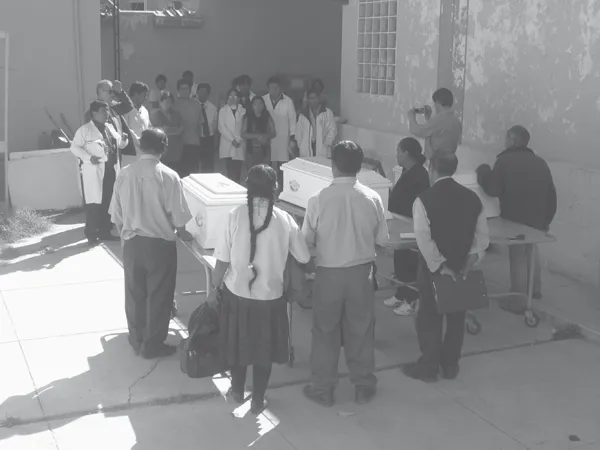

AT AROUND 1:30 p.m. on a sunny day in May 2007, in a small courtyard of the IML in Ayacucho, a group of forensic anthropologists start to arrange three small white coffins. These will contain the exhumed remains of three of the sixty-nine Quechua-speaking peasants massacred by the army in the Andean village of Accomarca in August 1985. The human remains are packed in sealed cardboard boxes labeled with the victims’ names that have been placed on three stretchers alongside the coffins. In white uniforms and wearing white sanitary masks and gloves, the experts proceed to transfer the remains from the boxes to the coffins, one victim at a time. They start with the bones, which they carefully arrange on a bed of rough cotton in the coffin, attempting to give the remains a human anatomic form. The expert in charge of handing the bones from the cardboard box to his colleague placing them in the coffin recites the name of each piece: “left femur,” “right femur,” “cranium,” “coccyx,” he says in a grave, soft voice as if reciting a litany. Once the arranged bones resemble a human form, the experts place on top of them the relevant rugged clothes recovered during the exhumation and proceed to seal the coffin with screws. They repeat the same steps for the other two victims, in a procedure we may call a bureaucratic reconstitution of the human body of victims of state terror.

When the coffins are ready, the official ceremony of restitution of the victims’ bodies to their relatives begins. This legal act is not open to the public; it takes place within the premises of the IML and is attended only by the victims’ direct relatives, leaders of their association (AFAPVDA),1 their lawyer, and other supporting professionals, including myself. Besides Ayacucho’s high-ranking legal and forensic authorities and the IML personnel who have been summoned to participate in the ceremony, no other local, regional, or national authority is present—not even a Catholic priest, whose presence in this kind of ceremony has become usual. The legal act unfolds in an atmosphere of uncanny intimacy, as if, rather than presenting a public performance of sovereignty, the law would prefer to animate a kind of private, face-to-face encounter between the dead, the survivors, and the state. Were it not for the presence of a local TV news reporter, I would have thought that the legal authorities did not want the public to know about the event.

The speech by the Fiscal Decano Superior of Ayacucho (Ayacucho’s district general attorney) makes it strikingly clear that this is not a public—hence political—act, but rather a legal and bureaucratic—hence private—act. Addressing the relatives who stand behind the coffins, the fiscal begins a formulaic speech by offering them condolences on behalf of the legal and forensic institutions. He emphasizes the “great responsibility” both institutions have before the nation at large and each of the relatives of people who, like those whose remains they are now returning, have been killed. He says that both institutions have fulfilled their duty because the IML professionals have worked hard to complete the identification of the victims and determine the causes of their deaths. “Now,” he says, “they can be offered a cristiana sepultura [proper burial].”2 In this way, he concludes, both institutions “have completed a task the law entrusted us.” I note here that the fiscal does not make any reference to the massacre, nor does he speak of retribution or reparation. His politically sanitized speech is chiefly concerned with the legal return of the victims’ bodies to their relatives for a private cristiana sepultura.

Celestino, president of the relatives’ association, takes the floor on behalf of the bereaved to thank the authorities and forensic experts for their work.3 He follows the fiscal’s script in saying that now that the work of the legal institutions is complete, the families will finally be able to recover the remains of their slaughtered relatives, even if these are just bones, to offer them a proper burial. But then, his speech resituates the act in the political realm. Visibly moved, Celestino says that the massacre has left a deep wound that the survivors will not be able to forget, ever. The forensic work has demonstrated that this was “genocide” and thus corroborates the claims about the atrocity of the massacre they have made ever since the event.4 Among the victims, he says, were not only newborns and elders, but also pregnant women. He goes on to say that forensic work is helping to demonstrate the truth in many other cases like Accomarca. He concludes that all this evidence backs the relatives’ claims for justice, and if the legal authorities are indeed committed to the truth, the perpetrators must be punished so as to prevent the repetition of this kind of atrocity in the future, anywhere in the country.5

We are all noticeably affected by Celestino’s speech. A relative’s description of the massacre as genocide resonates with the way the fateful event entered into a national narrative of the internal war. On August 14, 1985, four platoons of a special division of the army closed in on the village from four directions and gathered the villagers in an expanse known as Llocllapampa in an adjacent ravine. Since many adult men managed to escape, most of those assembled were elders, women, and children. The soldiers forced them into two contiguous huts and separated some women from the group to rape them. Then, after the orders of two young officers, the soldiers shot at the huts with their automatic rifles and grenade launchers. Following the killing, the military set the huts on fire with the intention of destroying the victims’ bodies and proceeded to strip the village of anything remaining that could be of value to the survivors. When the patrols left, the terrified survivors returned to the site of the mass killing to hastily bury the burned remains of their relatives in mass graves in the very place they had been killed.6

The massacre took place during the Peruvian Army’s scorched-earth campaign in the 1980s, when practically the entire Ayacuchano countryside was considered a “red zone,” meaning that the area had been deeply infiltrated by the Shining Path. However, the case was distinctive because it happened at the start of Alan García’s first term as president. García had won the election with the promise to change his predecessor’s counterinsurgency approach. News of the killing reached Lima, and the recently elected congress responded quickly with the appointment of a commission of inquiry, which concluded that the massacre constituted a case of gross violation of human rights and had to be prosecuted in the civilian courts. García fired the top military commanders for their attempt to cover up the abuses. Because of this swift official acknowledgment, Accomarca became one of those cases that, in the words of Ignatieff (1996, 113), narrows down the “range of permissible lies.”

However, the military claimed jurisdiction over the case and handed down lenient sentences, mostly administrative in character. Furthermore, in 1995 the Fujimori regime passed a blanket amnesty law that not only closed the legal case but also rehabilitated the military officers involved in the massacre. The nullification of the amnesty law in 2001 allowed civilian courts to reopen the case in 2003, after nearly two decades of impunity. As part of the new criminal investigation, the court ordered the excavation of the unmarked mass graves where terrified survivors had hastily buried the remains of their slaughtered relatives. A professional team of forensic archaeologists from the IML was in charge of the procedures, which began in May 2006 with the exhumation of three victims whose identification was easier because they were, uncharacteristically, buried in marked individual graves.7

Yet despite the prominence of the case in the national narrative of the internal war, on that afternoon of May 2007 at the IML premises in Ayacucho, the remains of the first three legally identified victims of the massacre were returned to their relatives for cristiana sepultura in a discreet and low-profile ceremony. Following the speeches by the fiscal and Celestino, the staff of the IML offered their condolences to the relatives. Then, bringing the bureaucratic act to an end, a clerk asked the relatives to sign and fingerprint the death certificates and forms acknowledging receipt of the bodies. Once the paperwork was complete, the clerk gave copies to the relatives and, echoing the fiscal, told them, “With this you will be able to bury your relatives; you will offer them a ‘cristiana sepultura’ [Con esto van a poder enterrar a sus familias; con esto van a darle ‘cristiana sepultura’].” The relatives thanked the clerk. We then took the coffins and left the IML. We had to wait for a while in the building’s entryway because some taxi drivers refused to transport the coffins. Eventually, after offering to pay much more for the ride than usual, we managed to get cabs and take the coffins to the lawyer’s assistant’s office—where they stayed until the next morning, when we carried them back to the village (Figure 1.1).

By mid-2007, gone were the days when the remains of rural Quechua-speaking victims of violence and atrocity were returned to their relatives in high-profile ceremonies of reburial. For about two decades in Peru, in an arresting manifestation of the unequal impact of the internal war on the body politic, the bodies of victims of violence had lain hastily buried wherever they had fallen or had been thrown in clandestine graves scattered throughout former war-torn rural areas. This situation was meant to change with the postconflict project of exhumation and reburial launched in 2001 in the context of the democratic transition that followed the collapse of the Fujimori regime in late 2000. During the first two years of the project, which coincided with the CVR’s tenure, the authorities performed three major public ceremonies of reburial to officially dignify victims of violence. But following the end of the CVR’s mandate, these high-profile ceremonies were reduced to discreet and formulaic bureaucratic acts, as the scene narrated above shows.

FIGURE 1.1. Survivors of the 1985 Accomarca massacre receiving the remains of their slaughtered relatives, Ayacucho, May 2007.

In this chapter I offer a partial history of how the question of recovering the remains of victims of violence for proper burial came to occupy center stage in Peru’s postconflict project of nation-making. In contrast to the well-known cases of Argentina, Chile, and Guatemala, in Peru exhumations are not primarily meant to dismantle the long-term effects of years of military dictatorship by recovering the remains of victims of campaigns of state terror. While including victims of state terror, in Peru exhumations also aim at recovering victims of the Shining Path within a broad moral framework that seeks to offer due recognition to all forgotten victims of violence—a move that is akin to what Verdery (1999, 47) sees nationalisms typically doing in their projects of nation-building, namely, “repossessing ‘our’ dead.” In Peru, the project of offering recognition to ignored victims of violence through proper burial was born with the notion that it would help to bridge the historical gulf that has separated white/mestizo, Spanish-speaking mainstream Peruvians from indigenous, Quechua-speaking peoples. In the CVR’s view, this gulf was, in the end, the ultimate cause of violence and prevents Peruvians from becoming a fully realized political community (see the Introduction).

I begin by tracing the political trajectory that led to the articulation of a broad project of reckoning with past violence, including a truth commission, exhumations, and prosecutions, as a result of the influence of international human rights law and global humanitarianism. I then examine the ways in which a project of forensic exhumation that started with the specific goal of shedding light on the whereabouts of the disappeared by the forces of the state ended up as a project of the exhumation and reburial of forgotten victims of both the Shining Path and the army. I also examine the ways this project of reckoning became a project of postconflict necro-governmentality aimed at structuring the field of possible action and speech of victims and survivors, as well as the population, regarding past violence. Finally, I briefly visit the three ceremonies of reburial the CVR performed to show how Quechua survivors received, deflected, accommodated, and contested this project to put forward their own projects of reckoning.

Internal War and the (First) Postwar Period

One of the peculiarities of Peru’s internal war is that it happened under formally elected civilian regimes. The violence broke out in May 1980 with the Shining Path’s campaign to overthrow the state, right before the inauguration of Peru’s first elected government after twelve years of military rule.8 The group’s initial symbolic act was to burn ballot boxes in Chuschi, a remote village in the Andean Quechua-speaking department of Ayacucho. The insurrection soon spread throughout the region, one of Peru’s most impoverished areas. In response, the newly elected regime of Fernando Belaúnde (1980–1985) embarked on a brutal counterinsurgency campaign that made extensive use of the state of emergency and granted the military unrestrained powers to confront the Maoists. Following doctrines of national security, the army targeted rural populations that they accused of supporting the guerrillas and deployed strategic forts in areas they considered “red zones.” Under the state of emergency, massacres, torture, and the disappearance of terrorism suspects became standard state practices in these areas, but Belaúnde denied their occurrence—setting the script of denial and silencing that later governments would follow.9

This strategy of state terror did not prevent the Maoist insurrection from expanding to other rural areas. Some communities formed government-supported civil patrols to fight the guerrillas and committed state-authorized violence, and the war escalated. The Shining Path retaliated with a terror campaign of its own, targeting local authorities, small landowners, popular leaders, and leftist opponents whom the Maoists accused of being state agents. In 1984 the MRTA entered the internal war, further expanding violence to other rural areas such as the central and southern Andes as well as the central Amazonian basin and the Huallaga region. By the mid-1980s most Peruvians lived under a state of emergency.

In 1985 President Alan García (1985–1990) came into office with the promise of changing his predecessor’s human rights policy. However, he soon backpedaled and embraced the military’s approach. During his regime, the internal war made its brutal practices visible to the rest of the country, including Lima—which until then had been relatively untouched. In June 1986, the Peruvian military extrajudicially executed more than three hundred incarcerated terrorism suspects as part of the state’s response to a prison mutiny that the Shining Path organized in Lima and El Callao to force their political demands upon the government. This event marked the final failure of García’s promise and constituted a further escalation of violence in the midst of a grave economic crisis that brought Peru to the brink of collapse by the late 1980s. Also during this period paramilitary groups flourished, killing alleged supporters of the guerrilla groups. At the time, Peru regularly appeared on the annual list compiled by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights of countries with the highest number of political disappearances in the world (Poole and Rénique 1992, 12).

President Alberto Fujimori came to power in 1990 during one of the most difficult periods in Peru’s recent history. His regime stabilized the economy through severe structural adjustment policies and the imposition of a neoliberal market economy, following an autogolpe (se...