- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Essay Film After Fact and Fiction

About this book

Nora M. Alter reveals the essay film to be a hybrid genre that fuses the categories of feature, art, and documentary film. Like its literary predecessor, the essay film draws on a variety of forms and approaches; in the process, it fundamentally alters the shape of cinema. The Essay Film After Fact and Fiction locates the genre's origins in early silent cinema and follows its transformation with the advent of sound, its legitimation in the postwar period, and its multifaceted development at the turn of the millennium. In addition to exploring the broader history of the essay film, Alter addresses the innovative ways contemporary artists such as Martha Rosler, Isaac Julien, Harun Farocki, John Akomfrah, and Hito Steyerl have taken up the essay film in their work.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Film & Video1

BEGINNINGS

FIGURE 1.1 Hans Richter, Inflation, 1928.

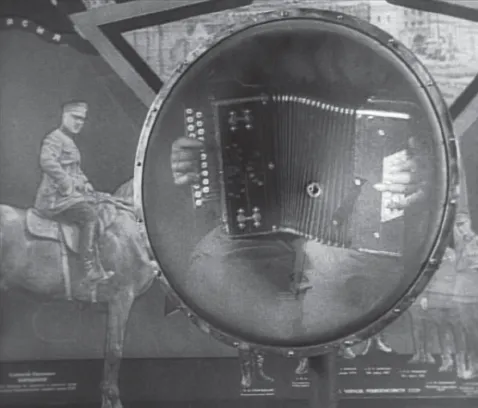

FIGURE 1.2 Dziga Vertov, Man With a Movie Camera, 1929.

The “essay” is the unmediated literary expression of this strange border area between poetry and prose, between creation and persuasion, between an aesthetic and an ethical stage.

—MAX BENSE, “ON THE ESSAY AND ITS PROSE”

Writing about Dada filmmaker Hans Richter in 1964, critic Jay Leyda lamented in a footnote, “today the ‘film essay’ form is almost totally, and incomprehensibly, ignored. The only modern film-maker who employs a witty variation of it is Chris Marker.”1 With this remark, Leyda makes two important observations: first, he implies that the essay film was recognized and practiced by a prewar and even presound generation of filmmakers; second, he draws attention to the fact that by the midsixties—an otherwise vibrant time for film development, experimentation, and exploration—the essay film was relatively ignored. The first part of Leyda’s comment, which suggests that there was an earlier moment when essay films received considerable attention, needs elaboration before one can understand the critic’s dismay at the decline of essay films in the late 1950s and 1960s. Leyda’s pronouncement also raises several other questions central to this study: What are the theoretical underpinnings of the essay film? Why was the genre ignored in the late fifties and sixties? Why did it explode once again a decade later? And why does it continue to thrive well into the twenty-first century?

Leyda locates the emergence of the modern essay film in Hans Richter’s Inflation (1928).2 Richter sought to make a film that would address a question that was central for him: “What social purpose does cinema serve?” He believed that cinema’s “artistic development as a whole and the development of each individual sector in every one of its forms” could only be properly understood if one continuously posed such a question.3After seven years of making films in which formal experimentation took priority over any social content, Richter was ready to pursue a new tack. Inflation constituted his first concrete conceptualization of an alternative cinematic form, one that was neither pure aesthetics nor simple reportage. As Richter wrote shortly after completing Inflation, “the path of theatre-freed film follows two directions: one in the pursuit of so-called unstaged shots, which are the technical base of weekly recordings of reality, the main proponent and director of this type of cinema is Dsiga Werthoff [sic]; the other type of film is that without plot, theme or narrative—the so-called ‘absolute film’.”4 Although he oversimplified Vertov’s project, Richter’s statement indicates his awareness of how limited the genre of nonfiction was by the late 1920s.

Following his training in the fine arts, Richter, one of the key players of the German Dada, sought in his early cinematic experiments to translate abstract painting directly into the medium of film.5 Throughout the 1920s, however, he gradually moved away from abstraction and toward figural representation. Initially Richter believed that “the abstract form offers film unusual possibilities because: 1) it allows for the possibility that the artistic expression can be realized free of all associations and coincidences; and 2) nonrepresentational, abstract ‘signs’ are, for us, the most persuasive and strongest means for expression.”6 Hence the abstract nature of his rhythm films and especially his borrowing of the shape of the Suprematist square in Rhythmus 21. But Richter soon realized that “abstract form in films does not mean the same as in painting where it is the ultimate expression of a long tradition of thousands and thousands of years. Film has to be discovered in its own property.”7 This attentiveness to the specificity of the filmic medium led Richter to dramatically alter his style in favor of using representational forms and human figures as initially exemplified in Filmstudie (“Film Study,” 1926).

Two years later, with Inflation, he took his theory of film to another level. Like other nonfiction films at the time, Inflation was commissioned by the German production studio UFA (Universum Film AG) as a short to precede Wilhelm Thiele’s commercial feature, Die Dame mit der Maske (The Lady with the Mask, 1928). For Richter, Inflation’s potential to reach a mass audience cannot be overestimated; it prompted him to contemplate how best to pursue his social goals because this production would be screened not only for like-minded people but also for a much more diverse audience. The film would therefore have to cut a fine line between being critical and accessible. To that end, Richter advanced his use of montage to a new level. As marked by the subtitle, “A Counterpoint of Declining People and Growing Zeros,” the short consists of a rapid flow of superimposed images of abstract circles set in motion against a black screen. As they gradually come into focus, they are recognized as coins, which are replaced by ever-increasing quantities and values of banknotes juxtaposed with their equivalent in U.S. dollars. As the notes multiply, images of consumer goods, such as a sewing machine, an automobile, food, types of shelter, and the like, crowd the screen, followed by a series of close-up shots of human faces bearing anguished expressions suggesting poverty. The film then cuts to figures of wealthy businessmen, shot from a low angle to increase their stature and visual dominance. Clearly, they are engaged in the high-end trading of goods and stocks. The next sequence presents a well-dressed man who, viewers presume, is reading about his loss of fortune in a newspaper. In a brilliant montage of images, Richter transforms this figure from a position of bourgeois respectability to that of a beggar asking for handouts. Shots of “faceless masses” that lose their individuality to poverty increase, and the final minutes are filled with images of nihilist revolution as buildings collapse in a paroxysm of destruction and violence.

The rapid-fire cascade of images symbolically corresponds to the crisis in which Germany found itself, brought on by uncontrolled inflation. Thus Richter underscored a formal relationship between his film style and his subject matter. In Inflation the reference to the crisis is dual: on one hand it echoes the country’s materialistic socioeconomic collapse; on the other hand it self-reflexively mirrors the conceptual confusion concerning the condition of nonfiction film. A factual news report of the same length—eight minutes—could not convey the utter destruction or register the agonizing despair and anxiety caused by the financial crisis, which was leading to the physical and mental collapse of the German citizenry. A feature film would run the risk of turning a tragedy into a melodrama, with excessive attention diverted to stars, outweighing the attention paid to the crisis at hand. What makes Richter’s film so effective is that, through cinematic tools and the language of montage, superimposition, and stop-motion, it condenses a complex historical drama to deliver its message more directly than what could be achieved in a pure documentary. The film resonates with Benjamin’s theory that history is conceptualized in the dynamic image. Recalling Richter’s comment about the misleading effects of the photograph of a bucolic village, images alone do not reveal the problematic relationships that lie beneath appearance. In contrast, he posited film as the medium capable of providing a glimpse of the other side:

The cinema is perfectly capable in principle of revealing the functional meaning of things and events, for it has time at its disposal, it can contract it and thus show the development, the evolution of things. It does not need to take a picture of a ‘beautiful’ tree, it can also show us a growing one, a falling one, or one swaying in the wind—nature not just as a view, but also as an element, the village not as an idyll, but as a social entity.8

Through the use of fast-motion images, Inflation provides the spectator with a complex critical commentary on the crisis of inflation; it offers both a brief history and a projected future: the full collapse of the socioeconomic and political state. As such it is a cinematic essay that does not pretend to be a news report based on facts, a commercial feature, or an abstract art film; it stands as an impressionist meditation encoding sharp social critique.

Richter’s Inflation predates by a dozen years his “The Film Essay: A New Form of Documentary Film” (1940), a short text in which he formally introduced and described the new genre. At this stage, Richter conceptualized the essay film as a branch of documentary filmmaking, a form or variation of the dominant genre. Like Leyda, he retrospectively cited his own film Inflation as an early example of what an essay film might look like. Following World War I, the development of film technology, narrative complexity, editing techniques, and mise-en-scène capabilities enabled practitioners of the medium to become more conscious of its unique nature. It was then that film’s potential as a discursive seventh art was first glimpsed. Despite the evidence of essayistic traits or segments in early cinema, these were initially taken as discontinuous “experiments” rather than systematic attempts to produce a new genre. Reflecting on early cinema, in 1925 Jacques Feyder observed that it consisted of “‘essays,’ various experiments, tentative trials and errors.” He proposed that “anything can be translated onto the screen; anything can be expressed in images. It is possible to derive a fascinating fiction film from the tenth chapter of Montesquieu’s Esprit des lois as well as from a page of [his] Physiologie du marriage, or a paragraph from Nieztsche’s Zarathustra as well as any novel of Paul de Kock.” Feyder understood the act of “translation” as a process that is no longer purely linguistic but can be intermedial in the shift from the written text to moving images. He stressed the need to “understand the importance of these words: to make visual. In them lies the whole art of cinegraphic transposition.”9 Feyder’s nontraditional concept of translation resonates with Walter Benjamin’s notion that translation is above all a manipulation of “modes” that allows for different expressions in new arrangements or forms.

For Richter, however, practice and experiment came prior to formalizing ideas in writing. After completing Inflation, he made several sketches for cinematic projects, including his Super Essay Films (1941), which he was unable to realize due to material circumstances. As a film, Inflation constitutes the first concrete conceptualization of an alternative cinematic form, one that is neither pure aesthetics nor simple reportage. Moreover, Richter explained that he employed the term “essay” because of its significance in literature as a form that can make difficult and dense topics understandable. Yet he cast the film essay as between genres, merging documentary with experimentation and art such that it does not limit the filmmaker to the reproduction of facts. Richter explains:

The essay film, in its attempt to make the invisible world of imagination, thoughts, and ideas visible, can draw from an incomparably larger reservoir of expressive means than the pure documentary film. Since in the essay film the filmmaker is not bound by the depiction of external phenomena and the constraints of chronological sequences, but, on the contrary, has to enlist material from everywhere, the filmmaker can bounce around freely in space and time. For example, he can switch from objective representation to fantastic allegory and from there to a staged scene; the filmmaker can portray dead as well as living things, and artificial as well as natural objects.10

Richter’s concept resonates with Lukács’s formulation of the literary essay, which postulates that the latter originates from the science of art but has radically departed from the constraints of “dry matter” and moved into “free flight.”11 Richter hoped that this creative and imaginative form would hold the attention of spectators and allow them to comprehend difficult theoretical constructions.

The significance of Richter’s Inflation and his text “The Film Essay” increase when considered in the cinematic landscape of the 1920s and 1930s. Along with better-known cinematographic works, such as F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) and Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid (1921), two particular films—Richter’s Rhythmus 21 (1921) and Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922)—helped shape and define nonfiction filmmaking. British documentary theorist and filmmaker John Grierson hailed the latter as the seminal inspiration of documentary filmmaking. In “The First Principle of Documentary” (1932), Grierson differentiated Nanook from earlier forms of nonfiction films such as actualities, newsreels, and travelogues because it initiated a change “from the plain (or fancy) descriptions of natural material, to arrangements, rearrangements, and creative shapings of it.”12 From that perspective, Nanook and Flaherty’s subsequent film Moana (1926) constitute significant interventions in a field dominated by superficial facts. As Grierson put it in an early lecture:

In documentary we deal with the actual and in one sense with the real. But the really real, if I may use that phrase, is something deeper than that. The only reality which counts in the end is the interpretation which is profound…. But I charge you to remember that the task of reality before you is not one of reproduction but of interpretation.13

In “The Film Essay,” Richter also extolled Flaherty’s Nanook as well as his later Man of Aran (1934) as models for innovative documentary filmmaking.

Richter’s Rhythmus 21 was equally as significant to nonfiction filmmaking as Nanook, but it was intended for a different public. Ushering in the school of abstract filmmaking and inspired by the paintings of Kazimir Malevich, the film offers a black and white study of Suprematist squares and rectangles that change in size and depth through a series of rhythmic evolutions. The number “21” in the title refers to the year the film was made. The prior year, Richter had collaborated with fellow artist Viking Eggeling to produce a pamphlet, “Universelle Sprache” (“Universal language”), in which, as he recalled in 1965, they tried to defend the thesis “that the abstract form offers the possibility of a language above and beyond national frontiers.” For Richter and Eggeling, an art based on national or cultural identification should be shunned in favor of productions that achieve transcendent or non-community-specific communication. As they elaborated:

The basis for such a language would lie in the identical form of perception in all human beings and would offer the promise of a universal art as it had never existed before. With careful analysis of the elements, one should be able to rebuild men’s vision into a spiritual language in which the simplest as well as the most complicated, emotions as well as thoughts, objects as well as ideas, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Beginnings

- 2. Speaking Essays Or Interruptions

- 3. The Essay Film As Archive And Repository Of Memories, 1947–1961

- 4. The Essay Film As The Fourth Estate

- 5. The Artist Essay: Expanding The Field And The Turn To Video

- 6. New Migrations: Third Cinema And The Essay Film

- 7. Beyond The Cinematic Screen: Installations And The Internet

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series List

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Essay Film After Fact and Fiction by Nora M. Alter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.