![]()

MY FAMILY’S STURGEON

FOR MANY years my mother’s family traditionally broke the Yom Kippur fast with a lavish meal at her parents’ home. Her father Charlie had done very well as an attorney active in the movie business and, along with his wife Bertie, enjoyed hosting large events at their capacious Central Park West apartment. A few years before I was born, my mother’s new husband brought his parents Abraham (we called him Abe) and Florence (whom we did not call Flo) to join the Schwartz clan’s meal. After the usual round of early 1950s cocktails, the group moved to the dining table, only to see a sturgeon laid out for the fish course. As Orthodox Jews, Abe and Florence were horrified. There was no question among the rabbis they followed that sturgeon was forbidden for Jews to eat. End the Jewish High Holy days by sharing a table with a treif animal? Unacceptable!

The result was a family confrontation, which I learned about over fifty years later from my father and mother. In his firm voice, Abe announced that he was not going to sit down at the table with a treif fish. Charlie, an articulate adherent of Conservative Judaism, vigorously defended sturgeon as kosher. References to Jewish law and fish anatomy flew back and forth across the room in front of anxious—and quite hungry—children and relatives. To preserve family peace (but also not conceding the point), Charlie had the sturgeon removed so that his in-laws would sit down and the meal could begin. After all, sturgeon had been a source of disagreement among Jews for one thousand years, and an answer was not to be found on an empty stomach.

FIGURE 1.1 Author’s family, Waldorf Astoria Hotel, June 1955, on the occasion of his parent’s fourth wedding anniversary. From left to right: Louise Horowitz, David Horowitz, Stuart Schwartz, Doris Schwartz, Ernest Schwartz, Florence Horowitz, Charles Schwartz, Bertie Schwartz, and Abraham Horowitz. Personal collection of Roger Horowitz.

The case of my family’s sturgeon offers a starting point to appreciating kosher law’s complexity and its place in the Jewish faith. “Judaism is fundamentally a way of life,” Bertie and Charlie astutely observed in their 1947 book, Faith Through Reason.1 Defining what food is fit and proper for Jews to eat reflects Judaism’s concern with practice and how its rules seek to embed observance in seemingly mundane routines. However, among a people scattered throughout the Western world, periodically uprooted by eruptions of anti-Semitism, ever encountering new climates, animals, plants, and foods, “daily life” was not a stable category. Judaism’s very concern with the practical and ordinary made kosher law engage with the endlessly complex profane world, in many places and in many cultures, repeatedly generating debates in which the rabbis of the past were interrogated to understand the complexities of a highly varied present.

Kosher law begins with the Jewish Torah, the five books of Moses—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. As the foundation of Judaism, the spare phrases in these books were the source for all future definitions—and disputation—over kosher food’s boundaries. Distinguishing clean from unclean in the animal kingdom is first explained in Leviticus 11:3 through 11:47 and then repeated in Deuteronomy 14:4 through 14:20. Understanding sturgeon started here, with the requirement in Deuteronomy 14:10 for acceptable animals “that live in water” to have “fins and scales.”2 Sturgeon seemed to have both—but determining its kosher status turned out to be a lot more complicated.

What complicated matters was the forced transformation of Jewish society with the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E. and the deportation of most Jews from what had been their homeland. A religion constituted around devotion and sacrifices at a central temple survived by becoming the Rabbinic Judaism that holds sway today, a religion defined by widely decentralized forms of observance adjudicated by an ecclesiastical caste. New rules elaborating acceptable behaviors and practices, promulgated orally, were redacted (written down) into two collections over the next five hundred years, one developed by the rabbis who remained in the historical lands of the Jews and the second cataloged by the thriving Jewish society in Baghdad, where many had taken refuge. Of these, the latter Babylonian Talmud would become the enlarged foundation of Jewish law for a civilization bound by a set of beliefs and practices. Composed of the Mishnah, a set of concise rules, and the Gemara, a record of rabbinic debates over those rules, the Talmud runs over five million words and forms the principal basis for the halacha—Jewish law.

From this watershed two different types of requirements would enter the halacha—biblical commandments, based directly on the Torah and rabbinic elaborations of those commandments deemed necessary to buttress observance. Rabbis became judges, with the authority to pasken (rule) on whether a particular practice was acceptable under Jewish law—such as whether it was permissible to eat sturgeon. Not all Jews accepted this profound change in their religion; the most durable dissenters, the Karaite sect, rejected rabbinic authority and with it the Talmud. But the vast majority of Jews followed the rabbis, and the consolidation of Judaism into a religion defined, above all, by the everyday practices expected of its adherents, rather than the exceptional obeisance performed at a central shrine.

With the concern over everyday practices came a necessary elaboration of many terse statements in Leviticus and Deuteronomy. To return to my family’s sturgeon: as Jews dipped their nets into new rivers and seas far from their original lands, what were their rabbis to make of the fish they caught? Pulling unfamiliar fish out of nets made the biblical rule hard to interpret—what was a fin and what did it mean to have scales? The Mishnah, reflecting rabbinic opinions of the second-century C.E., clarified the aquatic anatomical requirement by defining fins as appendages that helped fish swim and scales as flat material attached to the fish’s exterior. The Gemara’s commentaries on the Mishnah, redacted in the sixth century, had more to say because of questions raised about new varieties of fish caught by Jews, probably mackerels and sardines. Fish without scales when young were acceptable if they grew them later, as were fish that shed scales once caught. Scales also received a more exacting definition, as equivalent to kaskasim, from 1 Samuel 17:5, which described the Philistine champion Goliath wearing “a breastplate of scale armor”—also translated as a “coat of mail.”

Sturgeon still seemed to fit. They had fins in abundance, along with several rows of tough protuberances running up and down their sides. Yet were these kaskasim? Scraping them off with conventional fish knives was impossible; the sturgeon’s “scales” were so deeply embedded in the flesh that doing so also tore the skin. The biblical analogy—the term kaskasim—did not provide a self-evident analogy. Certainly a person could easily doff a coat of mail and keep their skin intact; seen in that light, the sturgeon’s protuberances were not scales. But a coat of mail was composed of many individual small metal pieces that could not be removed from the coat without irreparable damage. Could this perhaps also explain the sturgeon’s outer layer?

Close arguments over the text’s meaning were shadowed by a deeper dilemma for kosher law—the challenge of minhag, or local customs. A people who spread through the trading towns of the Mediterranean basin of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, often in very small and widely dispersed settlements, naturally experienced wide divergences in dietary practices. With rabbis having authority to approve foods as kosher, so long as those decisions could provide a clear source in the Torah and Talmud, Jews could develop varied customs without feeling they were departing from their faith. Their rabbi approved—how could there be a problem? Local divergences were overlaid with a profound split of Jews into two discrete religious communities—the Sephardi who lived under Muslim rule, and the Ashkenazi in Christian Europe. Determining acceptable foods became bound up with the larger issue of whether to accept local minhagim (plural of minhag) and, if not, how to eliminate them.

FIGURE 1.2 Sturgeon. J. G. Woods, Natural History Picture Book (London: George Routledge, 1867), 66.

The great problem of standardizing observance among a dispersed people motivated Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, the great Jewish thinker known as Maimonides or the Rambam, to compile his remarkable work of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah, in the late twelfth century. Seeking to quiet the cacophony of opinions among rabbis, his controversial work avoided references to past opinions and instead presented a digest of Jewish law—and with the Rambam’s spin. Some Ashkenazi were deeply offended at the pretension of a Sephardi living in Egypt determining, without references, the corpus of Jewish law; a few European Jewish communities even burned copies of the Mishneh Torah in protest.

The Rambam’s restatement of Jewish law on permissible fish varieties added an important requirement, that scales should be removable. Certainly this could be read to strengthen the case against sturgeon, as its protuberances were so tough that typical fish scalers were ineffective. But, in a separate ruling, Maimonides permitted Turkish Jews to consume sterlet, a species of sturgeon found in the Black Sea. An earlier twelfth-century ruling by the French halachic authority Rabbeinu Tam (Jacob ben Meir) similarly permitted Turkish Jews to eat sterlet. Sturgeon thus remained ambiguous, generally out of favor among Ashkenazi Jews, but acceptable in some places among the Sephardim.3

Despite Maimonides’ assertion that, with the Mishneh Torah’s publication, “a person will not need another text at all with regard to any Jewish law,”4 it did not become authoritative. Ignoring other rabbinic opinions and only including his own conclusions in the text offended many contemporaries. His method was fundamentally at odds with that of Ashkenazi rabbis influenced by Rashi, the immensely popular eleventh-century French rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, whose commentary on the Torah and Talmud is widely used today. Rashi’s school became known as the Tosafot, literally the commentators, for their emphasis on extended exploration of the Talmud’s texts. Beginning with the early printings of the Talmud, publishers would place Rashi’s commentary on one side of the main text and the combined observations of the Tosafot rabbis on the other. By seeking to avoid a discussion with other texts, Maimonides became just one voice among many—a powerful voice to be sure, but not the last word on Jewish law.

A far more influential effort to standardize Jewish law came from within the commentary tradition. Rabbi Joseph Caro, one of the great Jewish thinkers of the Middle Ages and a Sephardic Jew (like Maimonides), had both an encyclopedic mind and a systematizing temperament. Caro followed the model of an earlier effort to summarize Jewish law, the Arba’ah Turim (often referred to simply as the Tur) completed in the fourteenth-century by Rabbi Jacob ben Asher (known as Rabbeinu Asher) whose father was part of the Tosafot school. The Tur restructured summaries of Jewish law into four “rows”—daily life, dietary laws, marriage, and civil and criminal law—rather than follow the Talmud’s organization. Caro first wrote a massive review of the Tur called the Beit Yosef before publishing a far shorter summary in 1542 that he called the “set table”—the Shulchan Aruch. Benefiting from the arrival of the printing press, it circulated widely within the Jewish world over the next few decades.

Caro consolidated much of current Jewish law regarding food into the section of the Shulchan Aruch called the Yoreh De’ah; henceforth all debates about kosher food in some way trace back to this work. Initially, however, Caro’s effort generated a round of new controversies. His principal sources for rabbinic opinions were Rabbi Asher ben Jehiel (father of the Tur’s author and known as the Rosh), Maimonides, and Rabbi Isaac Alfasi—one Ashkenazi and two Sephardim; when they disagreed, Caro adopted the majority opinion, giving his decisions a decidedly pro-Sephardic cast. Caro also dismissed many Ashkenazi minhagim, viewing these local iterations of Jewish law as inconsequential at best and at odds with Jewish traditions at worst.

Polish rabbi Moses Isserles (known as the Rama) was one of Caro’s most formidable critics; but his very differences would make the Shulchan Aruch widely accepted. Rather than author a separate volume, he wrote a line-by-line commentary called the Mapah, or the “tablecloth,” which he placed on top of the “set table” of the Shulchan Aruch. In so doing, Isserles created a combined volume integrating Sephardic and Ashkenazi views that would have authority throughout the Jewish world. His success also reaffirmed Jewish law as an ongoing debate among authorities. Subsequent volumes of the Shulchan Aruch contained the often conflicting opinions of both Caro and Isserles; over several centuries the book grew to accommodate additional rabbinic commentaries, generating ever more expansive editions. (Interestingly, the incomplete English translations of the Shulchan Aruch summarize the text without distinguishing between Caro, Isserles, and other commentators.)5

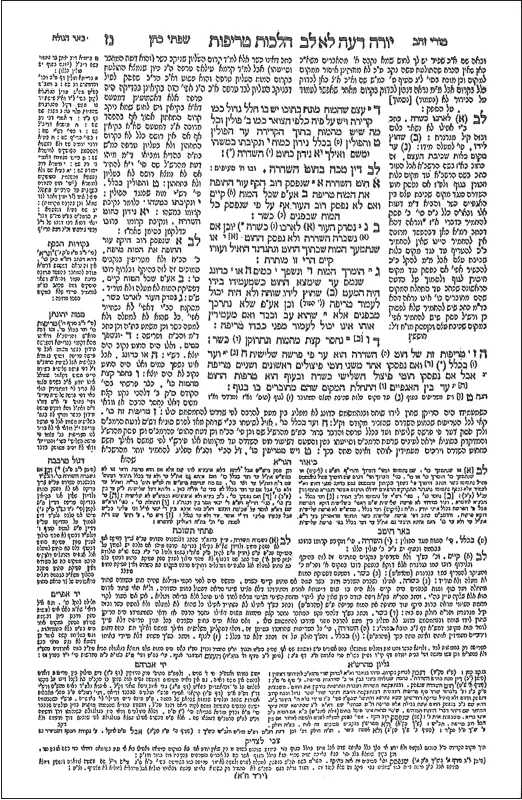

FIGURE 1.3 A page from the 1873 edition of the Shulchan Aruch published in Vilna, Lithuania, that illustrates how the original text by Rabbi Joseph Caro appeared in dialogue with commentaries by other rabbis. The largest text in the upper center is from Caro; it is interspersed with sentences in fine type that are Rabbi Moses Isserles’s comments on Caro. On either side and at bottom in smaller type are later rabbinic commentaries. S. I. Levin and Edward Boyden, The Kosher Code of the Orthodox Jew (New York: Hermon, 1975), frontpiece. Courtesy University of Minnesota Press.

Creating the Shulchan Aruch as a dialogue also maintained sturgeon’s disputed status within the Jewish world. In section 83:1 of the Yoreh De’ah, Caro simply restated Maimonides opinion that scales were the “peels” set into the skin. Isserles extended this argument by specifying that such peels only qualified as s...