eBook - ePub

Sexual Politics

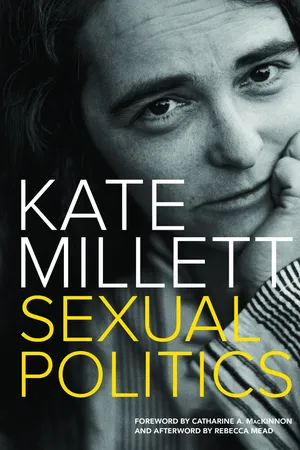

About this book

A sensation upon its publication in 1970, Sexual Politics documents the subjugation of women in great literature and art. Kate Millett's analysis targets four revered authors—D. H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, Norman Mailer, and Jean Genet—and builds a damning profile of literature's patriarchal myths and their extension into psychology, philosophy, and politics. Her eloquence and popular examples taught a generation to recognize inequities masquerading as nature and proved the value of feminist critique in all facets of life. This new edition features the scholar Catharine A. MacKinnon and the New Yorker correspondent Rebecca Mead on the importance of Millett's work to challenging the complacency that sidelines feminism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sexual Politics by Kate Millett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminist Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

II

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

THREE

The Sexual Revolution

FIRST PHASE

1830–1930

POLITICAL

DEFINITION

The term “sexual revolution” has such vogue at present it may be invoked to explain even the most trivial of socia-sexual fashions. Such usage is at best naïve. In the context of sexual politics, truly revolutionary change must have bearing on that political relationship between the sexes we have outlined under “theory.” Since the state of affairs defined there as patriarchy had obtained for so long and with such universal success, there seemed little reason to imagine it might alter. Yet it did. Or at least it began to—and for nearly a century it must have looked as though the organization of human society were about to undergo a revision possibly more drastic than any it had ever known within the historical period. During this time it must have often appeared as if the most fundamental government of civilization, patriarchy itself, was so disputed and besieged that it stood at the verge of collapse. Of course, nothing of the sort occurred: the first phase ended in reform and was succeeded by reaction. Nonetheless, very substantial change did emerge from its revolutionary ferment.

Just because the period in question did not in fact complete the drastic transformation it seemed to promise, it might be well to speculate for a moment upon what a fully realized sexual revolution might be like. A hypothetical definition may be of service in measuring the shortcomings of the first phase. It might also be of use in the future since there is reason to suppose that the reaction which set in after the first decades of the twentieth century is about to give way before another upsurge of revolutionary spirit.

A sexual revolution would require, perhaps first of all, an end of traditional sexual inhibitions and taboos, particularly those that most threaten patriarchal monogamous marriage: homosexuality, “illegitimacy,” adolescent, pre—and extra-marital sexuality. The negative aura with which sexual activity has generally been surrounded would necessarily be eliminated, together with the double standard and prostitution. The goal of revolution would be a permissive single standard of sexual freedom, and one uncorrupted by the crass and exploitative economic bases of traditional sexual alliances.

Primarily, however, a sexual revolution would bring the institution of patriarchy to an end, abolishing both the ideology of male supremacy and the traditional socialization by which it is upheld in matters of status, role, and temperament. This would produce an integration of the separate sexual subcultures, an assimilation by both sides of previously segregated human experience. A related event here would be the re-examination of the traits categorized as “masculine” and “feminine,” with a reassessment of their human desirability: the violence encouraged as virile, the excessive passivity defined as “feminine” proving useless in either sex; the efficiency and intellectuality of the “masculine” temperament, the tenderness and consideration associated with the “feminine” recommending themselves as appropriate to both sexes.

It seems unlikely all this could take place without drastic effect upon the patriarchal proprietary family. The abolition of sex role and the complete economic independence of women would undermine both its authority and its financial structure. An important corollary would be the end of the present chattel status and denial of rights to minors. The collective professionalization (and consequent improvement) of the care of the young, also involved, would further undermine family structure while contributing to the freedom of women. Marriage might generally be replaced by voluntary association, if such is desired. Were a sexual revolution completed, the problem of overpopulation might, because vitally linked to the emancipation of women, cease to be the insoluble dilemma it now appears.

Such conjecture leads us a long way from the period under discussion. What are its claims to have made a beginning at sexual revolution? One might object, that since the Victorian period was so notoriously inhibited, the era between 1830 and 1930 could accomplish nothing at all in the area of sexual freedom. Yet it is important to recall that as sexual suppression in the form of “prudery” reached a crisis in this period, only one course out of it was possible-relief. The last three decades of the nineteenth as well as the first three decades of the twentieth century were a time of greatly increasing sexual freedom for both sexes. This in particular meant the attainment of a measure of sexual freedom for women, the group who in general had never been allowed much, if any, such freedom without a devastating loss of social standing, or the dangers of pregnancy in a society with strong sanctions against illegitimate birth. The first phase achieved a good measure of sexual freedom and/or equity by struggling toward a single standard of morality. The Victorians worked rather illogically at this in two ways. While they strove to remove the onus from the “fallen woman,” they tried with a frequently naïve optimism to raise boys to be as “pure” as girls. However humorous a spectacle they present in these efforts, theirs was the first period in history that faced and tried to solve the issue of the double standard and the inhumanities of prostitution. A superficial knowledge of the reactionary era which succeeded the first phase might lead one to imagine it to be the more significant era of sexual freedom. Such is not in fact the case, for the liberalization of this period is hardly more than a continuation or diffusion of that begun before it. Often subverted for patriarchal ends it acquired a new exploitative character of its own. Any increase in sexual freedom for women in the period 1930–60 (for at its close the first phase had given them a rich increase) is probably due less to social change than to better technology in the manufacture of contraceptive devices and their proliferation. Wide distribution of what is as yet the most useful of these, “the pill,” falls outside the counterrevolutionary period. Save for this handy specific, the “New Woman” of the twenties was as well off, and possibly better provided with sexual freedom, than the woman of the fifties.

During the first phase, the most important problem was to challenge the patriarchal structure and to furnish an initial impetus for the enormous transformations a sexual revolution might effect in the areas of temperament, role, and status. It must be clearly understood that the arena of sexual revolution is within human consciousness even more pre-eminently than it is within human institutions. So deeply embedded is patriarchy that the character structure it creates in both sexes is perhaps even more a habit of mind and a way of life than a political system. Because the first phase challenged both habit of mind and political structures—but had much greater success with the latter than with the former—it was unable to withstand the onset of reaction and failed to fulfill its revolutionary promise. Yet as its goal was a far more radical alteration in the quality of life than that of most political revolutions, it is easy to comprehend how this type of revolution, basic and cultural as it is, has proceeded fitfully and slowly, more on the pattern of the gradual but fundamental metamorphosis which the industrial revolution or the rise of the middle class accomplished, than on the model of spasmodic rebellion (followed by even greater reaction) one observes in the French Revolution. Moreover, as the result of the rapid onset of a period of reaction, the first phase of the sexual revolution, like a moving object arrested mid-course, could not proceed even to the expenditure of its initial momentum. When we recall that this force has been revitalized only as recently as the last five years, and after some four decades of dormancy, we realize how amorphous and contemporary is the phenomenon we seek to describe—how recalcitrant before the precision historians seek to impose on more distant and defined events.

It cannot be emphasized too strongly that many, indeed most, of those first affected by the sexual revolution had neither a systematic understanding of it, nor foresight into its possible implications. Few, even of those who believed they were sympathetic, would have been committed to all its possible consequences. This is even true, to a varying degree, of its theorists: Mill never guessed at the effects it might have upon the family, and Engels seems quite unaware of its enormous psychological ramifications.

Changes as drastic and fundamental as those of a sexual revolution are not easily arrived at. Nor should it be surprising that such change might take place by stages that are capable of interruption and temporary regression. In view of this fact, the shortcomings of the first phase are understandable, and even the arrest and subversion of its progress which one encounters in the next era, while irritating and deplorable, is, to a degree, explicable as a comprehensible pause or plateau within an ongoing ‘process. Although the first phase fell woefully short of accomplishing the aims of its theorists and its most far-seeing exponents, it did nevertheless make some monumental progress and furnish a groundwork on which the present and the future can build. Although failing to penetrate deeply enough into the substructure of patriarchal ideology and socialization, it did attack the most obvious abuses in its political, economic, and legal superstructure, accomplishing very notable reform in the area of legislative and other civil rights, suffrage, education, and employment. For a group excluded—as women were—from minimal civil liberties throughout the historical period, their very attainment was a great deal to achieve in one century.

By an oversight too conspicuous to be accidental, historians have ignored the issue of sexual revolution, dismissed it with frivolous footnotes intended to demonstrate the folly of “votes for women,” or mistaken it for a trivial exhibitionist ripple in sexual fashion. Yet the great cultural change which the beginnings of a sexual revolution represent is at least as dramatic as the four or five other social upheavals in the modem period to which historiographical attention is zealously devoted.

Since the Enlightenment, the West has undergone a number of cataclysmic changes: industrial, economic, and political revolution. But each appeared to operate, to a large extent, without much visible or direct reference to one half of humanity. It is rather disturbing how the great changes brought about by the extension of the franchise and by the development of democracy which the eighteenth and nineteenth century accomplished, the redistribution of wealth which was the aim of socialism (and which has even had its effect upon the capitalist countries) and finally, the vast changes wrought by the industrial revolution and the emergence of technology-all, had and to some degree still have, but a tangential and contingent effect upon the lives of that majority of the population who might be female. Knowledge of this is bound to draw our attention to the fact that the primary social and political distinctions are not even those based on wealth or rank but those based on sex. For the most pertinent and fundamental consideration one can bestow upon our culture is to recognize its basis in patriarchy.

And it was against patriarchy that the sexual revolution was directed. Difficult as it is to explain such a radical shift in collective consciousness, it is almost as difficult to date it precisely. One might look back as far as the Renaissance and consider the effect of the liberal education it devised when such learning was finally permitted to women. Or one might reflect on the influence of the Enlightenment: the subversive impact of its agnostic rationalism upon patriarchal religion, the tendency of its humanism to extend dignity to a number of deprived groups, and the invigorating clarity which the science it sponsored exercised upon traditional notions both of the female and of nature. One might also speculate upon the marginal impetus provided by the French Revolution in breaking down other ancient hierarchies of power. Two beliefs which French radicalism had bequeathed to the American Revolution must also have had an effect: the idea that government relies for its legitimacy on the consent of the governed, and the faith in the existence in inalienable human rights. Out of this intellectual milieu came Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication, the first document asserting the full humanity of women and insisting upon its recognition. A friend of Paine and of French revolutionaries, its author was sufficiently in touch with revolutionary thought to urge the application of its basic premises to that majority still excluded from the Rights of Man.

Although it is beyond question that the culture of the eighteenth century in France had much to do with the suggestion that democracy apply in sexual as well as class politics, the purview of the present essay, coming as it does from America, must be confined to the English-speaking cultures, and as even the r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword by Catharine A. MacKinnon

- Introduction to the Illinois Paperback

- Introduction to the Touchstone Paperback

- Preface

- I: Sexual Politics

- II: Historical Background

- III: The Literary Reflection

- Postscript

- Afterword by Rebecca Mead

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index