![]()

ONE

Done and Undone

Meshes of the Afternoon and Witch’s Cradle

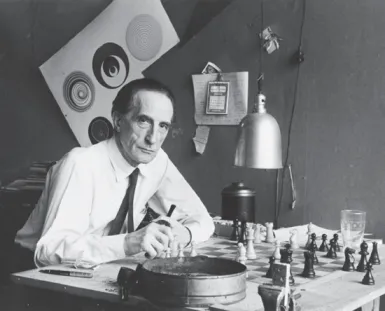

FIGURE 1.1 Marcel Duchamp in studio with chess board (with rotoreliefs behind him).

Photo: Sidney Waintrob, c. 1960. (Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Meshes of the Afternoon, Maya Deren’s earliest and best-known film, was made early in 1943 in collaboration with her then-newlywed husband, Alexander Hammid. A film that initiates Deren’s most substantive artistic interests translated into cinematic form, it was made in the first phase of Deren’s excitement about the qualities particular to the medium of filmmaking. Then and thereafter, in an auspicious beginning to a career as a filmmaker, Deren apprenticed herself to learn from Hammid, an already gifted filmmaker. Meshes is still one of the most recognizable touchstones of American experimental film, and it has shaped cinema history’s sense of Deren’s mission and legacy, a position it fulfills in several ways.1 However, only months later, Deren began work on a project on her own, filming in Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in New York, where Deren and Hammid moved shortly after finishing Meshes in their bungalow in the Hollywood hills. This second film was never completed. Its status as unfinished in fact flags several issues that prove important for understanding Deren’s developing sense of a cinematic ethos. Indeed, the case of Witch’s Cradle alerts us to the fact that Meshes, too, a seemingly definitive building block toward the legacy of Maya Deren, draws on the incompletion/completion balance to which Deren’s work over the years becomes increasingly prone.

This earliest period in Deren’s development as a filmmaker suggests that we should adopt a more nuanced view of the full range and trajectory of the completed films from 1943 to 1958, as well as a sense of how incomplete projects cast those films (including Meshes) into an altogether different relationship to each other and to experimental and documentary film practices. As we see in these two early films, a shifting balance between key binaries—incompletion/completion, control/contingency, stasis/motion, objective/subjective, etc.—propels her films. Deren’s work draws its vitality from negotiating these binaries without ever resolving them, drawing on the establishment of a “tension plateau” between elements. 2 Thwarting traditional narrative resolution and valorizing the process at least as much as the final product, each of these early films from 1943 to a greater or lesser degree owes its appeal and meaning to these negotiations, amounting to a not completely stabilized text and to varying degrees of success in the end.

MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON: HOLLYWOOD, 1943

Featuring Deren and Hammid in the main roles, the loose narrative sense of Meshes is steeped in the logic of dreamscapes, where repetition (the manufacturing of multiple Derens, the key/knife game, etc.) delays forward movement. Because of the circumstances of its genesis, spectators have sometimes been predisposed to view it as a psychological snapshot of an artistically inclined couple’s honeymoon, or as a portrait of the complex inner workings of their relationship to each other and to art. In her publicity materials for the film, Deren called it “A film concerned with the inner realities of an individual and the way in which the subconscious will develop an apparently casual occurrence into a critical emotional experience.”3

Whatever else it may do or mean, Meshes establishes key themes and a formal schematic upon which Deren will build for the remainder of her career. As Wendy Haslem has noted, Meshes generates an understanding of its themes “in the doubling, tripling and quadrupling of its central character (played by Deren) and in its cyclic narrative, a structure that seems condemned to repetition.”4 The film begins to hint at how a sense of incompletion inflects her work as a productive force, here through the non-ending forms of recursion, reflection, and circles.

A little history of Deren’s background leading up to the creation of her first film will shed light on the artistic motivations she was attempting to satisfy in the making of Meshes. Up to this point in her life, Deren dabbled with artistic and intellectual interests in poetry, dance, literature, photography, philosophy, religion, politics, and anthropology. Several of these preoccupations are mobilized creatively in this film and are then rejected, reworked, or transformed within subsequent films; a sense of the web of contexts for her interests will therefore prove useful as a baseline for how incompletion comes to dominate her aesthetic.

SOME ARTISTIC AND INTELLECTUAL INFLUENCES

Poetry was an especially powerful influence on Deren’s aesthetic for Meshes, and served as an undercurrent in the development of her later work as well. From early amateur versifying for her school journal, where she first received encouragement for her poems (she wrote home from boarding school in Switzerland: “I am hailed by all the girls as a sure poet.”),5 through writing her master’s thesis on poetry at Smith College in 1938–39, and at least until Deren met Hammid in 1942, Deren was a self-proclaimed poet, claiming it as her artistic calling. Hammid later described the genesis of Meshes as deriving from Deren’s poetic sensibility combined with his own cinematic expertise; he recalled that she was at that time “writing poetry always. It was one of her main ambitions. So she started with poetic images on paper, and I was visualizing them.”6 Their collaboration charted the movement from imagination to image, a trajectory important to understanding Meshes in particular as well as Deren’s work more broadly.

From the beginning of her work in film, Deren thought of visual images from the vantage point of language. She sought the immediacy of expression that she had had difficulty finding in her poetry. The remedy arrived for her once she began to work in film. As she recollected the matter, when she began to learn the craft of making films, she was suddenly able to translate her experience with poetry into the more direct image-making vehicle of cinema:

I was a poet before I was a filmmaker and I was a very poor poet because I thought in terms of images. What existed as essentially a visual experience in my mind…poetry was an effort to put it into verbal terms. When I got a camera in my hand, it was like coming home. It was like doing what I always wanted to do without the need to translate it into a verbal form.7

Whether in transcribing images from the imagination or, as she insists elsewhere, from reality itself,8 Deren eventually homes in on the idea of bringing nonverbal thoughts and perceptions—the domain of the imagination and image—more directly to the screen: “Fortunately, this is the way my mind works, and I could move directly from my imagination onto film.”9 Once she begins to identify as a filmmaker in earnest, poetry for Deren becomes a sort of poor man’s cinema. She had been trying to use poetry to accomplish what cinema is able to do naturally: build meaning through images (her faith in images may also explain the complete nonverbality of her films).

In this formulation of the difference between poetic and cinematic media, Deren directs attention to the Imagist desire to offer direct access to the thing, a point of reference she knew well, having completed her master’s thesis at Smith College on “The Influence of the French Symbolist School on Anglo-American Poetry.” As Renata Jackson has shown in detail, Deren read widely in French texts and in Anglo-American modern poetry and philosophy for her master’s thesis research and developed a number of her own ideas about the possibilities inherent in the cinema by applying principles first introduced to her in that reading.10 Significant here are both the Symbolists and the Imagists whom she places at the center of her study. Her notion of the image as a key to both poetic and filmic expression draws from these poets and thinkers.

Deren’s interest in poetry also carries with it the torch of an earlier avant-garde movement based in the artistic environment in France. Though she laments the “apparent failure of the film avant-garde of France” in the 1920s and 1930s, she inherits a great deal from their example, including the way in which she borrows from other art forms, especially poetry and dance, to think through cinema’s purview.11 The cross-medial fertilization of artistic endeavor rampant in France at that time—poets making movies, painters making books, etc.—would also trigger experimentation in the field of cinema as it redeveloped a provocative avant-garde beginning in the 1940s with Deren and her cohort.12

Deren’s work on the Symbolists and the Imagists focuses on how each group resolves the dilemma of how images generate ideas. Another parallel between these schools of thought and her films is their anti-Romanticism and call to return to formal demands.13 Although several critics of Deren’s films have described them as so focused on the self as to be narcissistic, her de-emphasis of the self even in her earliest films prefigures her experiments with ritualistic forms. This leads her to label her films “classicist,” and develops in earnest later through her critical statements toward ritual forms—especially in her most detailed theoretical statement of film theory, An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film, where she claims that by the time she made her fourth film she realized that all film form “should be ritualistic.” 14 Ultimately, the integrity of the created whole bears the weight in Deren’s vision of the artwork—not the individual parts, not the artist’s intent, but a workable, flexible combination of the two bent toward formal concerns.

In her thesis, Deren notes that the Imagists’ image is “a point of departure for mysterious distances.” 15 The “suggestiveness” of images informs Deren’s sense of how to effect a dramatic impact not bound to the exigencies of narrative nor even bound to the object itself. The act of making the image suggests a relay or a leap—something “new,” “startling,” and at “mysterious distances” from the thing itself—in the space of which the constitutive, separable parts of object, image, artist, and spectator are bound together. Literalization of the idea of “mysterious distances” arrives in Deren’s film work in her many traversals of disparate spaces with a match on action: e.g., a man lifts a leg in a forest and lowers it in a living room, fusing those spaces together through the image of the unified body.

The image corresponds directly to the world imaged for Deren: “Moreover, like the Symbolists, the Imagists rejected the conception of objective reality; they felt, instead, that the impression, or the Image, is not a symbol of reality but the reality itself, since one cannot distinguish between the object and its image.”16 The collapse between reality and the image, as we shall see, finds expression in Deren’s films and writings: she investigates the integrity of an image to see how far it will hold, interpreting the Imagist tenet “Direct treatment of the ‘thing,’ whether subjective or objective” liberally. Her practice anticipates André Bazin’s 1945 formulation of the relationship of object to image: “The photographic image is the object itself, the object freed from the conditions of time and space that govern it. […] It shares, by virtue of the very process of its becoming, the being of the model of which it is the reproduction; it is the model.”17 For Deren the image is always both objective (it exists in reality) and subjective (it exists in a specific way for the creator and spectator). The translation of ideas in her head to images on film depends upon the creative use of reality, to enact, in Bazin’s terms, an image’s “becoming.”

Her chapters on the history and theories of the Symbolist and Imagist movements culminate in a final chapter on Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, two poets who strongly condition her thinking. 18 Deren was drawn to Pound’s insistence on directness and to his later upheaval of the Imagist credo through Vorticist forms in their emphasis on movement and collision. Her interpretation of Eliot fixes on the relationship of Symbolist aesthetics and Classicism to his work. An interest in the “subjectivity” of an emotional response to art takes a prominent role here: Eliot-influenced subjectivity, to which Deren is drawn, retains the Imagists’ directness while representing subjectivity as a specific perspective on being in the world that may then serve as a relay from artist to audience. Deren sketches a movement from the personal to the (too-) objective and back to a place in the middle that balances both without losing either. This fulcrum point becomes the center of Deren’s cinematic subjectivity. 19 Her stance in relation to these issues stems from her work on the theory and history of poetry.

Deren also embarked on other writing projects in her pre-cinematic period, something she did not give up after turning to filmmaking. Her first husband, Gregory Bardacke, remembered her career goals just after they married in 1935 as being focused on writing: “Writing was her goal at that point. She was very serious about it. She would do anything at all—almost anything at all to promote her career.”20 During this period, Deren wrote a wide range of journalism, attempted several short stories, and penned at least one detective novel, as well as planning other creative and collaborative projects. The journalism in particular provides a background for Deren’s persistence in placing articles on the cinema in magazines and journals, as well as her ability to make connections. She tended to reach out to those who could teach her something or otherwise assist her in her pursuits.

For instance, in the few years leading up to her meeting and marrying Hammid, from late 1940 until January of 1942, she introduced herself to Katherine Dunham and convinced her to let her serve as her secretary while touring a production of Cabin in the Sky. In this capacity, Deren discovered that she was a fitting pupil for Dunham’s interests in ethnographic and terpsichorean pursuits, which would have profound impacts on her own travels to Haiti later in the decade. When she first began making films, Der...