![]()

PART I

INTEREST AND IDENTITY IN CHINESE FOREIGN POLICY

![]()

1

WHAT DRIVES CHINESE FOREIGN POLICY?

Vulnerability to threats is the main driver of China’s foreign policy. The world as seen from Beijing is a terrain of hazards, stretching from the streets outside the policymaker’s window to land borders and sea lanes thousands of miles to the north, east, south, and west and beyond to the mines and oilfields of distant continents.

These threats can be described in four concentric circles. In the First Ring—across the entire territory China administers or claims—the Chinese government believes that domestic political stability is placed at risk by the impact of foreign actors and forces. The migrant workers and petitioners who crowd the streets of Beijing and other major cities have been buffeted by the forces of the global economy, and their grievances have become issues in the West’s human rights criticisms of China. Foreign investors, managers, development advisers, customs and health inspectors, tourists, and students swarm the country—all with their own ideas for how China should change. Foreign foundations and embassies give grants and technical support to assist the growth of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

Along the coast to the east lie maritime territories, large swathes of which Beijing claims but does not control and which are disputed by its neighbors. These territories include islands and adjacent waters in the East China and South China seas. The most significant island is Taiwan, seat of the Republic of China (ROC). Located a hundred miles off the coast, Taiwan is a populous, prosperous, and strategically located island that China claims but does not control. The island has its own government and military force, formal diplomatic recognition from twenty-odd states, strong defense ties with the U.S., and political and economic relations with Japan and other countries around the world. To the far west, dissidents in Tibet and Xinjiang receive moral and diplomatic support and sometimes material assistance from fellow ethnic communities and sympathetic governments abroad.

Although no country is immune from external influences—via migration, smuggling, and disease—China is the most penetrated of the big countries, with an unparalleled number of foreign actors trying to influence its political, economic, and cultural evolution, often in ways that the political regime considers detrimental to its own survival. These themes are further explored in this chapter and chapter 10.

At the borders, policymakers face a Second Ring of security concerns, involving China’s relations with twenty immediately adjacent countries arrayed in a circle from Japan in the east to Vietnam in the south to India in the southwest to Russia in the north. No other country except Russia has as many contiguous neighbors. Numbers aside, China’s neighborhood is uniquely complex. The contiguous states include seven of the fifteen largest countries in the world (India, Pakistan, Russia, Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam—each having a population greater than 89 million); five countries with which China has been at war at some point in the past seventy years (Russia, South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and India); and at least nine countries with unstable regimes (including North Korea, the Philippines, Myanmar/Burma,1 Bhutan, Nepal, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan). China has had border disputes since 1949 with every one of its twenty immediate neighbors, although most have been settled by now.

Every one of these Second Ring neighbors is a cultural stranger to China, with a gap in most cases larger than that which the U.S., Europe, India, and Russia face with their immediate neighbors. Although Japan, Korea, and Vietnam borrowed some parts of their written and spoken languages and some Confucian beliefs from China, they do not consider themselves in any sense Chinese. The other neighboring cultures—Russian, Mongolian, Indonesian, Indian, and others—have even less in common with China. None of the neighboring states perceives that its core national interests are congruent with China’s. All the larger neighbors are historical rivals of China, and the smaller ones are wary of Chinese influence.

Complicating the politics of the Second Ring is the presence of Taiwan (which is also part of the First Ring). The overriding goal of its diplomacy, as we discuss in chapter 8, is to frustrate China’s effort to gain control. In doing so, it seeks support from other countries within and beyond the Second Ring. Taiwan is thus a major problem for Chinese diplomacy and counts as a twenty-first political actor on China’s immediate periphery.

Finally, the Second Ring includes a twenty-second actor whose presence poses the largest single challenge to China’s security: the U.S. Even though the U.S. is located thousands of miles away, it looms as a mighty presence in China’s neighborhood, with its Pacific Command headquarters in Honolulu; its giant military base on the Pacific island of Guam (6,000 miles from the continental U.S., but only 2,000 miles from China); its dominating naval presence in the South and East China Seas; its defense relationships of various kinds around China’s periphery with South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Kyrgyzstan; and its economic and political influence all through the Asian region. If the vast distances that separate the United States from China prevent China from exerting direct military pressure on it, the same is not true in reverse.

All in all, China’s immediate periphery has a good claim to be the most challenging geopolitical environment in the world for a major power. Except for China itself, Russia faces no contiguous country that is anywhere near its own size; its demographic and economic heartland in the European part of the country is buffered from potential enemies by smaller states; it has invaded its neighbors more often than it has been invaded by them; and it has not been attacked by a direct neighbor since the Russo–Japanese War of 1904–1905. Even more striking is the comparison of China’s situation with that of the U.S., a country that has only three immediate neighbors, Canada, Mexico, and Cuba, each much smaller, and that is separated by oceans from all other potential enemies.

Also unlike the U.S., China seldom has the luxury of dealing with any of its twenty-two neighbors in a purely bilateral context, a fact that brings into play a Third Ring of Chinese security concerns, consisting of the politics of six nearby multistate regional systems. Beijing’s policies toward North Korea affect the interests of South Korea, Japan, the U.S., and Russia; its policies toward Cambodia affect the interests of Vietnam and Thailand and often those of Laos—as well as the interests, again, of the U.S.; its policies toward Burma affect India, Bangladesh, and the nine states that are comembers with Burma in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)—and again, the U.S. Because of such links, China can rarely make policy with only one state in mind and can almost never make policy anywhere around its periphery without thinking about the implications for relations with the U.S. The map of Asia is too crowded for that.

This Third Ring of Chinese security consists of six regional systems, each consisting of a set of states whose foreign policy interests are interconnected. The memberships of some of the systems overlap. The six systems are Northeast Asia (Russia, the two Koreas, Japan, China, and the U.S.), Oceania (Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, twelve Pacific island microstates, China, and the U.S.), continental Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Burma, China, and the U.S.), maritime Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Brunei, the Philippines, China, and the U.S.), South Asia (Burma, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the Maldive Islands, Russia, China, and the U.S.), and Central Asia (Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, China, and the U.S.) (see frontispiece map). The aggregate number of states in the six systems is forty-five.2

China is the only country in the world that is physically part of such a large number of regional systems. (If the U.S. and Russia are engaged in even greater numbers of regional systems, it is not by the dictates of geography, but by choice.) Some issues are pervasive across all six systems (for example, China faces the U.S. presence in all of them, and in all systems its neighbors are wary of its rising influence), whereas some are distinctive to particular systems (such as the North Korean nuclear weapons issue in Northeast Asia and Islamic fundamentalism in Central, South, and maritime Southeast Asia). Each system presents multifaceted diplomatic and security problems.

These first three rings of security—from the domestic to the regional—thus present a foreign policy agenda of extreme complexity, which absorbs most of the resources China is able to devote to foreign and defense policy. Yet these three rings cover only about one-quarter of the globe’s surface if one leaves out the vast watery region dotted with the microstates of Oceania. The rest of the world—including eastern and western Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and North and South America—belongs to an outer, or Fourth Ring, of Chinese security.

China has entered this farthest circle in a big way only since the late 1990s and has done so not in pursuit of general power and influence, but, as we argue in chapter 7, to serve six specific needs: for energy resources; for commodities, markets, and investment opportunities; for diplomatic support for its positions on Taiwan and Tibet; and for support for its positions on multilateral diplomatic issues such as human rights, international trade, the environment, and arms control. Not only its goals but its tools of influence in the Fourth Ring are limited: they are commercial and diplomatic, not military or, to any significant extent so far, cultural or political.

To be sure, China’s weight in this wider global arena is enhanced by its demographic and geographic size, its trajectory of economic growth, its independence of the U.S., and its status as a permanent member of the UN Security Council. But in contrast to the U.S., Europe, and even to some extent Russia, and in common with regional powers such as Japan, India, Brazil, and Turkey, China seldom endeavors proactively to shape the politics of distant regions to its own preferences. Instead, it must deal with whomever it finds in power, and if that regime is overthrown, it seeks relations with its successor. China has arrived in the Fourth Ring as a dramatically new presence, but not in the role of what we would call a global power—at least not yet.

Within each of the four rings, China’s foreign policy agenda is seldom its policymakers’ free choice, as can sometimes be the case when the strongest powers take an initiative to oust a government or force a peace settlement in a region far from their own shores. Chinese foreign policy instead responds defensively to a set of tasks imposed by the facts of demography, economics, geography, and history.

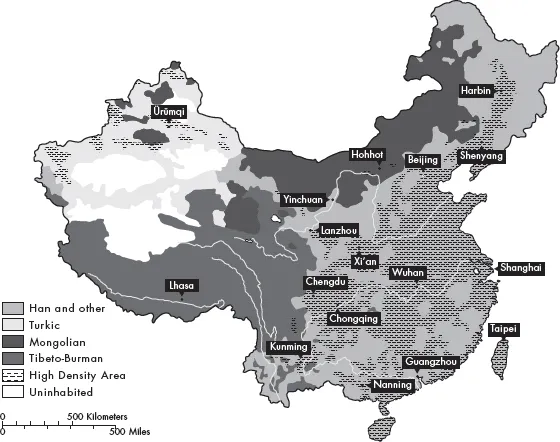

DEMOGRAPHY: HUGE, POOR, CONCENTRATED, AGING, AND ETHNICALLY DIVERSE

The problematic nature of China’s situation begins with its demography. China’s territory is about the same size as that of the U.S., but at 1.3 billion its population is more than four times as large. Three-quarters of the population is concentrated on about one-quarter of the territory, leading to intense pressure on both urban and rural living space. The demographic heartland is located in a 600-mile band along the eastern and southern coasts, with an outcropping along the Yangtze River reaching onto the Chengdu Plain in Sichuan (see the map showing the demography of China). It is roughly the size and shape of the American East Coast from Massachusetts to Florida, including Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Alabama, but contains five and a half times as many people as those states. The most heavily populated eighteen of China’s thirty-three province-level units have a combined population of 957 million, more than the cumulative populations of China’s eight most populous neighbors, not counting India.

The heartland produces 83 percent of the country’s GDP. It contains sixteen of the world’s twenty most polluted cities. Population is so dense that 70 percent of China’s rivers and lakes are said to be polluted, and the World Bank estimates that pollution reduces the value of China’s GDP by as much as 12 percent annually.

Even after decades of stellar economic growth, China’s people are relatively poor. In 2009, the country ranked 128 out of 227 in GDP per capita. Moreover, income is unevenly distributed: a strong share of the increased wealth has gone to a new class of the rich and ultrarich. Many urban residents are dissatisfied because of job insecurity, low wages, unpaid benefits, and land disputes. Rural residents—57 percent of the population by official government classification—resent their second-class political and economic status. An estimated 160 million rural people have migrated temporarily to the cities to do factory and construction work. Facing all these dissatisfied social groups, the government needs to improve incomes and welfare benefits to maintain political stability, but it can do so only gradually because of the huge cost.

For the longer term as well, the demographic structure of the heartland population is full of latent threats. Because the regime enforced a policy of one child per family starting in the late 1970s, there are now more old people and fewer young people than in a normal population distribution. By 2040, retired people will make up nearly one-third of the population, worse than the ratio in Japan today, and the number of children and elderly will nearly equal the number of working-age men and women. The burden on the working population will hold back economic growth and may create a shortage of military manpower. Even if the government were now to relax the one-child policy, as it has begun to do, the shortage of people in the reproductive ages will continue to create a shortage of children, causing the population to peak at about 1.5 billion around 2030 and then decline. As this happens, India will overtake China as the country with the world’s largest population and will enjoy the economic benefits of more workers and a lower ratio of dependents. China’s population-planning program also produced an imbalanced sex ratio because some families aborted female fetuses or in some cases even killed or abandoned baby girls. By 2030, China is expected to have 25–40 million surplus males, with unknowable consequences for social stability.

THE DEMOGRAPHY OF CHINA

Above and beyond the heartland towers a second China, remote and high, stretching as far as 1,500 miles farther to the west. The western thirteen of China’s provinces occupy three-quarters of China’s land surface but contain only a little more than one-quarter of its population and produce less than one-fifth of its GDP. These provinces contain most of China’s mineral resources and the headlands of its major rivers. Most of this area is mountainous or desert, and most of its people are poor.

Even though China’s fifty-five officially recognized national minorities constitute only about 8 percent of the country’s total population, several of the minorities living in the West have weak commitments to the Chinese state, strained relations with the central government, and active cross-border ties with ethnic kin in neighboring countries. This is especially true of two groups: the Tibetans, who live not only in the Tibet Autonomous Region, but also in parts of four other contiguous provinces; and the Uyghurs, who form the largest population group in the vast region of Xinjiang. These two populations occupy the extensive buffer area that has historically protected the heartland from the political storms of Inner Asia. Beijing nominally gives what it calls “autonomy” to 173 minority-occupied areas ranging from province-size regions such as Tibet and Xinjiang to counties, but these areas are in fact controlled by ethnically Chinese (that is, Han) administrators and military garrisons. The government invests major resources to assure its control over this far-flung domain, a topic we explore further in chapter 8.

ECONOMICS: FROM AUTARKY TO GLOBALIZATION

China made a strategic turn from autarky to globalization in the 1980s and 1990s that fundamentally altered its relations with the outside world. The turnabout generated new power resources but also new security challenges.

China traditionally was an economic world unto itself. The premodern economy did not support power projection beyond the borders, nor did it require initiatives in international trade or diplomacy. It produced little that could be sold abroad, needed little that was produced abroad, saved no money to invest abroad, and offered no skills to attract investors from abroad. After World War II, when other parts of Asia that started out with agrarian economies and Confucian cultures similar to China’s registered growth rates of 8–10 percent a year by producing consumer goods for the West, China did not have the same option of export-led development. For one thing, levels of global trade were too small both in absolute terms and as a proportion of world gross national product to accommodate China. Second, even had international markets been more inviting, China’s entry into them was barred by a trade embargo which the West imposed at the start of the Korean War and which it maintained later as part of the effort to drive a wedge between China and the Soviet Union (see chapter 3). The Soviet Union for its part—China’s ally in the 1950s—was recovering from World War II and gearing up its defense forces for the Cold War. It could give China only limited, although crucial, assistance, and this assistance came to an end with the Sino–Soviet split in 1960. For all these reasons, China in the 1960s and 1970s was the one major country whose domestic economy was completely isolated from the international economic system.

China’s leaders had to look inward fo...