![]()

1

The Modernist Impulse

SUBJECTIVITY, RESISTANCE, FREEDOM

Modernity is a crucial concept in contemporary discourse. It is often vaguely described as a set of cultural and political preoccupations that arose during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These involved the nature of moral autonomy, tolerance, the character of progress, and the meaning of humanity. Modernity justified itself through scientific rationality and an ethical view of the good life that rested on universal values and the democratic exercise of common sense. Civil liberties and the tolerance associated with a free public sphere were logically implied by these secular liberal notions, along with ideas concerning the rule of law and citizenship. All of this was part of an assault on powerful religious institutions and aristocratic privileges in the name of a liberal “watchman state” coupled with a free market. The rising bourgeoisie introduced a new economic production process that rested on the division of labor, standardization, bureaucratic hierarchy, and the profit-driven values of the commodity form. The use of mathematical or instrumental rationality by this class tended to define reality in such a way that qualitative differences were transformed into merely quantitative differences. Those who worked to create commodities were treated as a cost of production, or an appendage of the machine, while the accumulation of capital served to inspire all activity. The living subject (workers) that produced and reproduced society thereby appeared as an object, whereas the dead object of its activity (capital) appeared as a subject. The result was what first G. W. F. Hegel and then Karl Marx termed the “inverted world”—a world of modernity shaped by alienation and reification.

Modernism was the response to this world. The assault was launched by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The Discourses (1750), The Social Contract (1762), and Émile (1762) not only embraced nature as a standard for combating the illusions attendant upon progress and the alienation reflected in its arts and sciences. They also championed a new form of democratic community and a new pedagogy to educate the sensibility as well as the mind. Rousseau’s Confessions (1782) demonstrated a remarkable sexual frankness and a preoccupation with authenticity. Trends like “Storm and Stress” (Sturm und Drang) and schools like romanticism and classical idealism acknowledged their debt to Rousseau. Out of his vision other philosophers constructed their critique of materialism, utilitarianism, and the suffocating elements of industrial progress.

Aesthetic ideals such as the sublime arose with thinkers like Edmund Burke, Immanuel Kant, and Friedrich Schiller.1 Art would now refashion emotions like fear, anguish, and even terror in such a way that each member of the audience might feel sympathy for the persecuted and, recognizing himself in the other, a sense of common humanity and dignity. Works like J. W. Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) and Benjamin Constant’s Adolphe (1816) captured the world of youth with its Weltschmerz, along with the tensions between authentic feeling and the hypocrisy and prudery of established conventions. The emotional intensity and dramatic verve of Schiller’s The Robbers (1781) created a sensation—and it only made sense that his “Ode to Happiness” (1824) should have been employed by Ludwig van Beethoven for his Ninth Symphony (1824). The wonderful poetry of Lord Byron, John Keats, and Percy Bysshe Shelley echo these themes. All of them embraced a bohemian style that mixed an insistence on expanding personal experience with a hatred of injustice born of solidarity with the less fortunate. A stance emerged that would juxtapose the aesthetic (and often the premodern past) with the reality of modern life. These trends prefigured and shaped what would become known as modernism. But, ultimately, these earlier movements did not offer an overarching assault on society. Reinvigorating art was their purpose. Revolutionary politics was another matter. For the modernists, by contrast, the one was the precondition for the other. Or, better, they were one and the same.

Modernism would call into question every aspect of modern life, from the architecture through which our apartments are designed, to the furniture in which we sit, to the comic books our children read, to the films we watch and the museums we visit, to the experience of time and individual possibility that mark our lives. Modernists may have believed that they were contesting modernity, but their efforts and their hopes were shaped by it. Their activities legitimated what they intended to oppose. Their critique, in short, presupposed its object. Modernists believed that they were contesting tradition in the name of the new and the constraints of everyday life in the name of multiplied experience and individual freedom. These artists were essentially anarchists imbued with what Georg Lukács termed “romantic anti-capitalism.”2 They opposed the “system” without understanding how it worked or what radical political transformation required and implied. Oddly, they never understood how deeply they were enmeshed in what they opposed. Modernists envisioned an apocalypse that had no place for institutions or agents generated within modernity. Theirs was less a concern with class consciousness than an opposition to the alienating and reifying constraints of modernity. Unfettered freedom of expression and a transformation in the experience of everyday life were the modernists’ goals. Even when seduced by totalitarian movements, whether of the left or the right, most of them despised what Czeslaw Milosz called the “captive mind.” Not all the problems that they uncovered—sexual repression and generational conflicts, among others—required utopian solutions. But their utopian inclinations were transparent from the beginning. Modernists believed that the new would not come from within modernity, but would appear as an external event or force for which, culturally, the vanguard would act as a catalyst.

Modernism is not reducible to its artists, works, or intended purposes. The modernist ethos highlights experience in its immediacy and the constraints that tradition places upon it. Bohemian radicals everywhere sought to resist tradition and the ingrained habits of everyday life. Michel Foucault emphasized just this point by noting how modern painting derives from the new understanding of the “picture object” introduced by the spatial, perspectival, and lighting techniques of Manet.3 Modernists sought to break down the wall separating the audience from the work. Style, in short, went public, ultimately shaping the perception of the enemy and the self-professed political resistance of the artist. Liberal humanist Italy thus spawned an antihumanist and bellicose futurism, while an authoritarian-militarist Germany generated a mostly humanist and pacifist expressionism. Modernism surely underestimated liberalism, with its reliance on the individual as the cornerstone of society and its insistence on prohibiting only what is condemned by law. The liberation of experience was far more important. Intensity became the ethical purpose of life. Ludwig Rubiner—an expressionist poet and a democrat—put the matter bluntly in Man in the Middle (1918) when he wrote, “Politics is the public manifestation of our ethical intentions.”

Modernism was not about institutions; its advocates didn’t think about them. Their enemy was decadence, and in responding to it, they appropriated diverse contributions from nonwestern cultures. Painters and sculptors in particular, but also certain writers like André Gide and D. H. Lawrence, turned to Africa, Asia, and Latin America for inspiration. Modernists thereby transformed and broadened the understanding of art. Pluralism and tolerance lie at the core of modernism, but it never required liberal institutions to flourish.4 The Austrian, German, and Russian empires served as crucibles for modernism. Its symbolic power of resistance is, arguably, diminished in more liberal societies where the culture industry thrives on fads and artists are encouraged to challenge limits. Authoritarian regimes repress the new while liberal regimes domesticate it. For all that, however, modernism retains its salience, exhibiting what Ulrich Beck termed a “subpolitical” quality. It tests existing customs and mores by sparking the desire for new adventures, new experiences, and new ways of understanding the world. Modernism enlarges the world and strengthens the cosmopolitan sensibility. With its injunction to “make it new,” indeed, modernism serves as the inner core or existential truth of modernity.

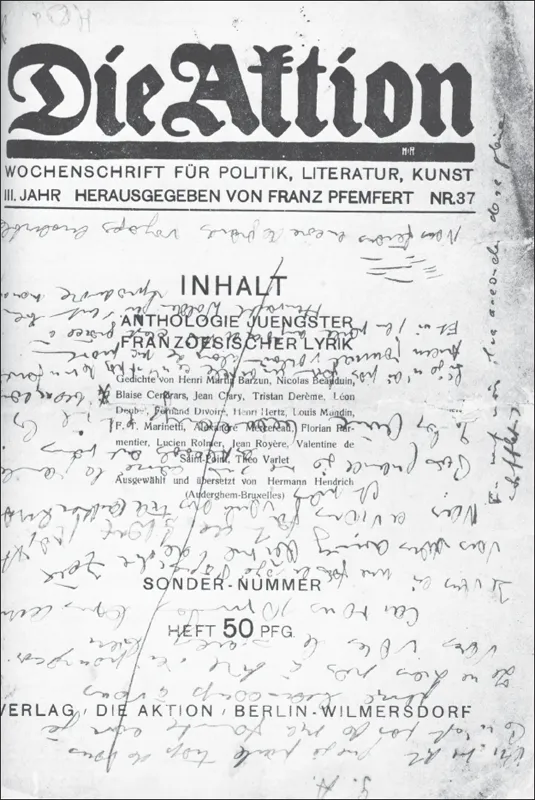

No wonder then that the modernist undertaking should have taken place in cities. The urban landscape breeds cosmopolitanism and the bohemian response to traditionalism. Journals like the expressionist Der Sturm and Die Aktion,5 the futurist Lacerba, and Révolution Surréaliste appeared and championed the new, not just in Berlin, London, and Paris but also in Barcelona, Bucharest, Budapest, Florence, Kiev, and elsewhere.6 An international avant-garde—a term first introduced by Henri St. Simon—crystallized throughout Europe. Its particular movements often overlapped. All of them opposed philosophical formalism, institutional politics, and an economy built on calculable profit and materialist values. Ironically, however, they all considered their actual admirers to be their implacable enemies. Their individualism, experimentalism, and cosmopolitanism appealed to the liberal elements of the bourgeoisie. Peasants and shopkeepers had little use for their assault on traditionalism and authoritarian attitudes. The bohemian style of the modernists, moreover, made them the object of scorn by a semiliterate working class living in hideous conditions and burdened with very different concerns.

Modernism was mostly immune to the influence of Marx. Most of its partisans were contemptuous of the seemingly more mundane concerns of the socialist labor movement and its cultural tastes. Few emphasized the disenfranchisement and systemic exploitation of the proletariat and even fewer participated in its political organizations. Modernists were more preoccupied with existential matters and aesthetic exploration—what Flaubert might have termed an education of the sentiments. They understood themselves as engaged in a “higher” politics whose agent, whatever it was, was not the working class. The modernist avant-garde was focused on neither reform nor revolution. Its members experimented with multiplying experience, broadening the possibilities of perception, exploding the habitual, and transforming the way in which people relate to one another. Intergenerational tensions were raised in works like Patricide (1922) by Arnolt Bronnen and The Maurizius Case (1928) by Jakob Wassermann. The devastating implications of sexual repression, innocence, and hypocrisy were given sensational expression in plays like Spring’s Awakening (1906) by Frank Wedekind and Julie (1888) by August Strindberg. Patriarchy and gender oppression were the themes of masterpieces like A Room of One’s Own (1929) by Virginia Woolf and A Doll’s House by Ibsen. Same-sex love was brought out of the closet in The Immoralist (1902) by André Gide and the poems of Gertrude Stein. All of this was connected with articulating a new sensibility; institutional power was an afterthought. The subpolitical became the substitute for politics.

FIGURE 1.1 Die Aktion magazine (1911–1932).

Modernists justified their cultural understanding of politics through a seemingly endless supply of manifestoes and philosophical tracts that usually combined a mishmash of half-baked claims.7 For all the bombast, there were no practical programs for social or political change. Modernists were content with imagining a new cultural community in which their radical individualism would blossom. Oscar Wilde is a case in point. His witty and satirical plays made him the toast of London, before his sensational trial left him bereft of friends and a disgraced exile in Paris.8 Wilde was a homosexual dandy with socialist sympathies who hated vulgarity as much as injustice. He exemplified that strange mixture of elitism and populism that marked the avant-garde. Author of a lovely essay, “The Soul of Man under Socialism” (1891), he may not have thought much about the means for bringing about a transformation in human nature, but, like so many other modernists, he did understand that the liberating quality of socialism depended on something other than more efficient production and more equitable distribution of wealth. Wilde symbolized the assault on Victorian prudery and hypocrisy. He also personified the bohemian opposition to the standardizing, mechanizing, and alienating tendencies of the commodity form and mass society.

Modernism can be understood as an antiauthoritarian reaction to modernity or, more precisely, the reification process usually identified with modernity.9 All the major movements and artists identified with modernism contested the sexual constraints of the Victorian age, the attitudes of their own national bourgeoisie, and the consensual and common-sense understanding of the real. Some modernists tended to the left and others to the right; some were advocates of technology and a ruthless realism, while others embraced the religious and the sentimental. For all that, however, there remains what Louis Althusser would have called the “problematic” of modernism. Only by focusing on that problematic is it possible to illuminate the contributions, contradictions, and utopian projections of the modernist enterprise

Modernists confidently considered their enterprise an apocalyptic breakthrough. They desired to reenchant and invigorate the world that modernity had disenchanted and deadened. This marked their rebellion and their rationality of resistance. It also generated a political outlook in which modernism was so often defined by what it opposed.10 That is why modernist artists could often comfortably stand on both sides of the political barricade and still treat one another as comrades. Those on the left like Émile Zola, Pablo Picasso, Heinrich Mann and others are well known. But modernism also had its famous right-wing partisans, including Maurice Barrès, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Wyndham Lewis, Ezra Pound, and a host of others whose stars have dimmed.11 These two political wings of the modernist movement knew one another, influenced one another, and—especially before the Russian Revolution of 1917—often associated with one another both at home and abroad.

Representatives from opposing political wings of the modernist movement still shared certain cultural convictions. These, I believe, centered on the existence of a common enemy and a common (if indeterminate) utopian ideal: the “cultural philistine” (Bildungsphilister) and the “new man” who would supplant him.12 Who is the cultural philistine? There is no clear answer. He is the anxiety-ridden petty bourgeois, the provincial fearful of the new, the liberal banker puffing his cigar, the old geezer admonishing the young, the schoolteacher eulogizing the classics, the censor intent on banning James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), the uneducated proletarian, the sexually repressed rationalist, the aristocratic traditionalist, or—thinking back to a song from the 1960s by The Kinks—“the well-respected man about town doing the best thing so conservatively.” An exact definition doesn’t matter; the cultural philistine was not the representative of any specific class, status group, or institution. Sometimes the modernists’ image of the cultural philistine perfectly fit with the stalwart of political reaction. The small-minded tyrant described so beautiful...