![]()

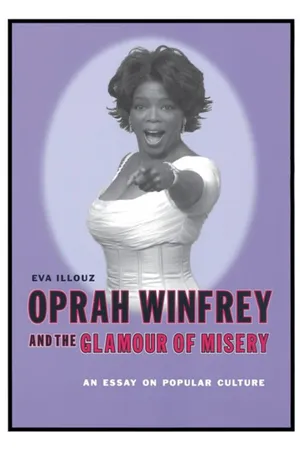

1 | INTRODUCTION: OPRAH WINFREY AND THE SOCIOLOGY OF CULTURE |

To our scholars, strangely enough, even the most pressing question does not occur: to what end is their work . . . useful? Surely not to earn a living or hunt for positions of honor? No, truly not. . . . What good at all is science if it ha no time for culture? . . . whence, whither, wherefore is all science, if it is not meant to lead to culture?

—Friedrich Nietzsche

Oprah Winfrey is the protagonist of the story to be told here, but this book has broader intentions: to reflect on the meaning of popular culture and to offer new strategies for interpreting that meaning. In that respect, this book is a long rumination on the current state of cultural studies, with two distinct purposes. The first is to move the study of popular culture away from the power-pleasure-resistance conceptual trio that has dominated it and to bring it within the fold of “moral sociology,” which has traditionally explored the role that culture plays in making sense of our lives and in binding us to a realm of values. The second purpose is to explore the methodological difficulties involved in capturing the “meaning” of a cultural enterprise as complex as that of Oprah Winfrey. In this sense, this study can be read as an exercise in cultural interpretation and, more specifically, in the interpretation of popular culture.

Oprah Winfrey is a particularly apt subject for these multiple tasks, for she offers a spectacular example of the ways in which a cultural form—the Oprah Winfrey persona—has assumed an almost unprecedented role in the American cultural scene. Oprah embodies not only quintessentially American values but also an American way of using and making culture. Oprah Winfrey has risen in only one decade to the status of richest woman in the media world—accumulating wealth equivalent to that of the GNP of a small country1—and her fame and her cultural role are unprecedented in television. An excerpt from the biography on her Web site makes this clear:

Oprah Winfrey has already left an indelible mark on the face of television. From her humble beginnings in rural Mississippi, Oprah’s legacy has established her as one of the most important figures in popular culture. Her contributions can be felt beyond the world of television and into areas such as publishing, music, film, philanthropy, education, health and fitness as well as social awareness. As supervising producer and host of The Oprah Winfrey Show, Oprah entertains, enlightens, and empowers millions of viewers around the world.

Oprah has been honored with the most prestigious awards in broadcasting, including the George Foster Peabody Individual Achievement Award (1996) and the IRTS Gold Medal Award (1996). In 1997, Oprah was named Newsweek’s most important person in books and media and TV Guide’s “Television Performer of the Year.” The following year, Oprah received The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences’ Lifetime Achievement Award. Also in 1998, she was named one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th Century by Time magazine. In November 1999, Oprah received one of the publishing industry’s top honors, the National Book Foundation’s 50th Anniversary Gold Medal, for her influential contribution to reading and books. She has also received seven Emmy Awards for Outstanding Talk Show Host and nine Emmy Awards for Outstanding Talk Show. In September 2002, Oprah was honored with the first-ever Bob Hope Humanitarian Award at the 54th Annual Prime-Time Emmy Awards˛. (http://www.oprah.com/about/press/about_press_bio.jhtml)

Oprah Winfrey is not only a famous character—a condition shared by many others. She is a cultural phenomenon. As an article published in Ebony put it: “From the beginning, her show has captured the American television psyche like nothing the industry has seen before or since. The fact is, since her show went national in 1986, it has remained head and shoulders above the others. All of them.”2

Her talk show has won thirty Daytime Emmy Awards, and, at the rather young age of 44, Oprah garnered the Lifetime Achievement Award. In 1994, she was named by Forbes as the highest paid entertainer (winning over such male media figures as Bill Cosby and Steven Spielberg). Oprah Winfrey is more than a taste maker; she not only embodies values that many Americans revere but also has invented a cultural form that has changed television and American culture. In 2000, anyone logging in at the world-famous Amazon.com bookstore could find a rubric entitled “Oprah Winfrey Books,” along with such general rubrics as “Fiction” and “Nonfiction.” These books were the novels chosen by Oprah Winfrey to appear in her famous monthly Book Club. Her choices alone have been decisive for the careers of numerous authors and publishing houses. Why? Because Oprah Winfrey has been one of the most important commercial forces in the U.S. publishing industry. In April 2000, Oprah even established a new magazine, O Magazine, which Newsweek called “the most successful magazine startup in history.”3

An article in Vanity Fair put the point aptly: “Oprah Winfrey arguably has more influence on the culture than any university president, politician, or religious leader, except perhaps the Pope.”4 Or, as writer Fran Lebowitz put it, “Oprah is probably the greatest media influence on the adult population. She is almost a religion.”5 I would even go a step further. In the realm of popular culture, Oprah Winfrey is one of the most important American cultural phenomena of the second half of the twentieth century, if we measure “importance” by her visibility,6 the size of the fortune she has managed to amass in one decade, the size of her daily audience,7 the number of imitations she has generated, the innovativeness of her show, and her impact on various aspects of American culture—an effect that some have called, somewhat derogatively, the “Oprahization of culture.” In 2001, the “Top Ten Words of 2001 Announced by Your Dictionary.Com” defined “Oprahization” facetiously but tellingly as follows: “Describes the litmus test of political utterances: if it doesn’t play on Oprah, it doesn’t play at all.”

The obvious cultural visibility and economic size of the Oprah phenomenon should provide a good enough reason to undertake a study of its meaning. Indeed, Oprah has such influence that she is an ideal example of those collective “big” cultural phenomena that sociologists of culture love to analyze because they reveal a society’s mindset.

But there is another reason why Oprah Winfrey is a compelling object of study. In spite of her popularity, or perhaps because of it, Oprah Winfrey has been the object of disdain on part of the “old” intellectual and cultural elites. In a 1993 Chicago Magazine article, Ms. Harrison, an essayist and fiction writer who in 1989 had written an in-depth profile of Oprah, was quoted as saying: “Her show . . . I just can’t watch it. You will forgive me, but it’s white trailer trash. It debases language, it debases emotion. It provides everyone with glib psychological formulas. These people go around talking like a fortune cookie. And I think she is in very large part responsible for that.”8

This echoes a more general disparaging view, aptly represented by Robert Thompson, director of Syracuse University’s Center for the Study of Popular Television, who said that talk shows exemplify the fact that “TV has so much on it that’s so stupid.”9 Like so many other elements of popular culture, Oprah Winfrey and her talk show have generated ritual declarations of disdain from public intellectuals, political activists, feminists, and conservative moral crusaders. Precisely for this reason, Oprah is of great value to the student of culture. The cultural objects that irritate tastes and habits are the very ones that shed the brightest light on the hidden moral assumptions of the guardians of taste.10 Such cultural objects make explicit the tacit divisions and boundaries through which culture is classified and thrown into either the trash bin or the treasure chest.11 Indeed, the criticisms of Oprah Winfrey offer a convenient compendium of the very critiques that are ritually targeted at popular culture. If talk shows systematically blur boundaries constitutive of middle-class taste, Oprah offers a privileged point from which to examine such boundaries, partly because she herself manipulates them in a virtuoso fashion.

With regard to the traditional corpus of studies in the sociology of culture, these are sufficient and even compelling reasons for studying Oprah Winfrey. Yet there is a last and perhaps most consequential reason why Oprah Winfrey is of such burning interest to the student of culture: she demands a drastic reconceptualization of popular culture. Indeed, “pleasure,” “power,” and “resistance”—the main concepts of cultural studies in the 1980s and 1990s—are inadequate in helping us to gain a deep understanding of her phenomenon.

Show after show, I was struck by the fact that Winfrey seems to bring us back to the question of the ethical force of cultural meanings, which has haunted sociology since the turn of the twentieth century. Oprah’s use of culture invites us to go back to Max Weber’s view that culture is a way to respond to chaos and to meaninglessness by offering rational systems of explanations of the world.12 Weber’s view, which was mostly applied to religious systems, should be extended to popular culture. Popular culture is not only about entertainment. It is also, more often than is acknowledged in cultural studies, about moral dilemmas: how to cope with a world that consistently fails us and how to make sense of the minor and major forms of suffering that plague ordinary lives. In this book I argue that Oprah Winfrey has become an international and a mighty (western) symbol, because she offers a new cultural form through which to present and process suffering generated by the “chaos” of intimate social relationships, one of the major cultural features of the late modern era.13 Oprah Winfrey shows us how to cope with chaos by offering a rationalized view of the self, inspired by the language of therapy, to manage and change the self. The Oprah Winfrey Show is a popular cultural form that makes sense of suffering at a time when psychic pain has become a permanent feature of our polities and when, simultaneously, so much in our culture presumes that well-being and happiness depend on successful self-management.

However, this “old-fashioned” approach to popular culture—viewing it as an arena in which the ethical orientation of the self is addressed—must be framed in radically new terms. For this “old” vocation of culture has been recast by Oprah Winfrey in an unprecedented new form. Oprah points to the fact that cultural objects are no longer defined by space, territory, nation, or technology. She is better understood as a criss-crossing of expert knowledge, multiple media technologies, and orality intertwined with multiple forms of literacy, overlapping media industries, cyberspace, support groups, and traditional charismatic authority. The Oprah Winfrey Show has a tentacular structure that defies boundaries and definitions of what constitutes a text. Its format and topic areas reach into the domains of the family (which includes topics such as intimacy, parenthood, divorce, and siblings), the publishing industry, various experts (psychologists, doctors, lawyers, financial consultants, et cetera), stars of the music and cinema industries, volunteer organizations, the legal and political systems, and, finally and most importantly, the singular, particular, and ordinary biography of the common man and woman.

Because this tentacular cultural structure stretches from the biographical to the transnational, from the personal life story to the economic empire, traditional models of cultural analysis fail, as they conceive of culture as bound by territory and nation or circumscribed within one social sphere (e.g., “family,” “mass media,” or “the state”). While these are still relevant dimensions of much of our cultural material, they cannot account for a form as meandering as that of Oprah Winfrey. While my previous book, Consuming the Romantic Utopia, examined the process by which a private practice—courtship—went to the public sphere of consumption and was commodified within and through icons of consumption, here I examine how the public sphere implodes from the multiplicity of private worlds it stages and how it builds new and unprecedented connections between the individual biography and the intensely commodified medium of television.

IN SEARCH OF MEANING

In the last decade, talk shows have come to occupy a central place in American television, a fact that has elicited public outcry over the vulgarization of culture as well as a flurry of studies on their meaning and impact. Because the topic has been so controversial, most studies have been preoccupied with the question of whether talk shows debase cultural standards and political consciousness. For example, for Heaton and Wilson (1995), talk shows crudely manipulate their guests; betray the basic moral code of truthfulness; are “voyeuristic,” “sensationalist,” and “sleazy”; encourage stereotyping; and debase standards of public debate.14 For many such commentators, the intense revealing of private life in public that is the distinctive mark of talk shows threatens a genuine public sphere, stereotypes women, encourages a culture of victimhood, and commercializes private life.

Other analysts beg for us to understand talk shows as a phenomenon that throws into question our conventional definitions of “public sphere.” In their excellent study of audiences’ responses to talk shows, Livingstone and Lunt have argued that talk shows in fact expand the scope of the public sphere.15 If classical liberalism holds that that sphere should include a homogeneous public whose members hold and discuss well-formed opinions, talk shows construct viewers as a fragmented plurality of publics, members of which enter the public sphere with half-formed opinions, life stories, and even emotions. This suggests that what counts as a public discussion has been enlarged to include topics not dreamed of by the theorists of liberalism.

In an even more pointed way, Shattuc has argued that, far from subduing women, talk shows engage them in a complex and fragile dynamic of empowerment, providing an arena in which to discuss “women’s issues” and giving voice to the voiceless. Such conclusions, in turn, suggest that we should revise our presumably gender-blind notions of “public sphere.”16 Finally, in his excellent study, Joshua Gamson (1998) has argued that talk shows deconstruct notions of gender and sexuality, thereby transforming our representations of sexual minorities and opening up the possibility for a more egalitarian politics of representation of these minorities.

In contradistinction to these studies, I focus on the Oprah Winfrey talk show first and foremost as the product of a set of intentions deployed by a cultural agent (see chapter 2). Thus, my interpretation of the Oprah Winfrey show is less interested in the politics of representation of her texts than in the moral positions she takes and makes manifest through her intentional manipulation of cultural codes (see chapters 4 and 5). I argue that, more than many televisual texts, as a text The Oprah Winfrey Show is inseparable from the set of intentions Oprah Winfrey tries to deliver to her viewers.

A COMPREHENSIVE APPROACH TO CULTURE

Broadly, the analysis of culture can be approached along three paths. The first is concerned with what we may call the realm of the “ethical”: that is, the ways in which culture bestows on our actions a sense of “purpose” and “meaning” through a realm of values or through powerful symbols that motivate and guide our action “from within.” This perspective approaches culture as the force that binds us to the social body through values, rituals, or morality plays.17 “Meaning” implies here a kind of energetic engagement of the self in a social and cultural community through the ...