![]()

ONE

The Emergence of an International System in East Asia

In the Beginning There Was China

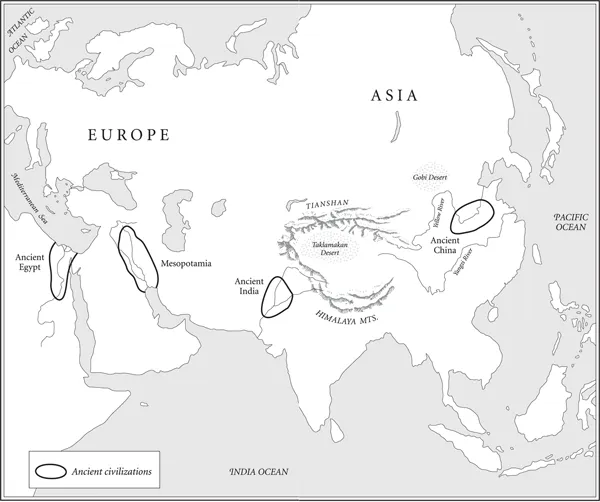

The origin of the state in East Asia remains shrouded in the mists of prehistory, but archeologists continue to find bits and pieces, potsherds, textiles, and bones, promising that someday we will be able to explain this and other ancient mysteries, to penetrate the fog of the distant past. For now we must be content to estimate that in the course of several thousand years before the so-called Christian Era, somewhere around 2000 BCE, people living in what is now east central China did create something akin to a state. Mesopotamia, Egypt, and South Asia had developed urban civilizations earlier, probably hundreds of years earlier. The Chinese state appears to have evolved independently, although before very long, perhaps three thousand or so years ago, contact with peoples far to the west is evidenced by the import of a variant bronze technology, the so-called “lost wax” method of casting. Recent discoveries in western China of the burial sites of Caucasians dating from around 1200 BCE suggest the possibility of other cross-cultural influences early in the history of the Chinese people.1

TABLE 1.1. Some Notable Dates of the Ancient World: 3500–1000 BCE

(Dates are approximate. Events in bold face are referred to in text)

| First year of Jewish calendar | 3760 BCE |

| Sumarian civilization in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) | 3500 BCE |

| Pyramids and Sphinx built at Giza, Egypt | 2700–2500 BCE |

| Indus Valley civilization in India | 2500–1500 BCE |

| Xia Dynasty in north China | 2000–1450 BCE |

| Hammurabi of Babylon provides first legal system | 1792–1750 BCE |

| Peak power of Nubian kingdom of Kush (Sudan) | 1700–1500 BCE |

| Shang Dynasty in north China | 1450–1122 BCE |

| Moses leads Israelites out of Egypt | 1225–1200 BCE |

| Destruction of Troy | 1184 BCE |

| Zhou Dynasty in north China | 1122–221 BCE |

| David becomes king of all Israel | 1000 BCE |

Perhaps most striking to the modern reader, however, is the relative speed with which an international system developed in East Asia, foreshadowing much of what is known of the practice of international relations. Theoretical works written by Chinese more than two thousand years ago are still studied today in military academies in the United States as well as China. Critical concerns that have challenged policymakers throughout the ages—the role of morality in foreign policy, the balance of power, questions of when to use force and when to appease, and of appropriate military strategy when force is the option chosen—were debated by Chinese analysts throughout much of the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1122–221 BCE). Realpolitik and Machtpolitik as concepts of international politics may evoke images of amoral Germanic statesmen, of Otto von Bismarck and Henry Kissinger, but the Chinese were practicing—and criticizing—them while Central Europe was still populated with neolithic scavengers.

The path to an understanding of the emergent international system leads through more than a thousand years of Chinese history. From archeological evidence we know something of the material culture, even the religious practices of the ancient peoples of Central Asia, Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia, but the earliest indications of statecraft are to be found in China. The Chinese call these formative years, 2000–221 BCE, the Sandai or Three Dynasties (Xia, Shang, Zhou) era. For most of these years there are at least traces of records of the contacts between the Chinese and their neighbors, including the nomadic peoples of Inner Asia and especially the relations of the first “Chinese” to those ultimately absorbed into the Chinese state. It should never be forgotten that the early Chinese did not expand into empty space, but rather by force into territories already occupied by peoples of similar race and language. Like all the world’s empires, the Chinese Empire was based on conquest, the subjugation of militarily inferior peoples whom the Chinese portrayed as subhuman to justify their own conduct.

Archeologists and students of ancient Chinese history, examining objects such as pottery, stone tools, bronze, and oracle bone inscriptions,2 have concluded that several similar but discrete neolithic cultures, including the Xia, Shang and Zhou, existed simultaneously in north China in the second millennium BCE. The Xia were the first to organize a political entity that might be called a state. Leaders of that entity had a conception of boundaries and distinguished between those who accepted their rule and the “others.” Members of the Xia state identified themselves as the Hua-Xia (flowers of summer) and disdained those who did not, who were different, whether living among them or outside the borders of their state. With creation of the state came the conception of the defense of its people and its boundaries, necessitating military power.3

The Xia had external relations with culturally similar people such as those who lived under Shang and Zhou rule. They also encountered dissimilar peoples, some speakers of Indo-European languages to their west, some of nomadic stock. These contacts were often warlike, involving the expansion and contraction of Xia influence, sometimes peaceful, such as the exchange of goods, intermarriage, and diplomacy. But at the dawn of the twenty-first century, despite extraordinary archeological work by scholars of the People’s Republic of China, we still know little about the details.

In mid-fifteenth century BCE, with the defeat of the Xia by their eastern neighbors, the Shang, the record improves. The recent recovery of thousands of Shang oracle bones provides precious insights into foreign relations, as well as into the Shang view of the world in which they lived. It is apparent, for example, that during the nearly five centuries in which they dominated north China, Shang rulers perceived of a world order in which their territory was at the center, ringed by subordinate states.

By the time of the emergence of the Shang state, the people of north China had evolved a settled agrarian style of life in which most lived clustered around a local leader. Inscriptions on oracle bones and bronzes indicate that they had developed a written language, recognizable to modern scholars as Chinese. A highly sophisticated indigenous art, most notably painted pottery and bronzes, had emerged from local neolithic cultures. Shang bronzes, cast by a unique piece mold method, were the most complex technologically that the ancient world had ever seen, far surpassing bronze age works of contemporary Mesopotamia—and incomparably imaginative.

The state was a monarchy imposed on a shifting federation of autonomous groups whose loyalty depended on the leadership ability of the king—or shared lineage with him. The king was central and the composition of the state varied in accordance with his ability to attract and hold allies. The state was also a theocracy, in which the king was the main diviner. One historian, David Keightley, has described Shang China as a “politico-religious force field” whose authority fluctuated over areas and time.4 At the head of both the political and religious orders stood the king.

In brief, more than 3,000 years ago, just as Cretan civilization was spreading across the Aegean to Greece, a people were creating the institutions of a state in China, defining themselves and their borders, and attributing differences to, “objectifying,” those who were not members of their state. Those who lived beyond the frontier were understood to be culturally different, “barbarians.” The state was perceived as encompassing all of the civilized world and its king proclaimed supremacy over all of that world and exclusive access to the supreme divinity. Here was the foundation of the later Chinese conception of the relationship between the emperor and the ruler of the heavens.

Groups drawn into the Shang state, such as the Zhou who eventually destroyed the Shang dynasty, accepted the king’s claim to universal dominion. As subjects are wont to do, some offered tribute, sending gifts to their ruler. Conceivably this practice evolved into the elaborate tributary system of a later time. Such gifts had symbolic value, attesting to the monarch’s overlordship—and may have had economic value as well. Some peoples to the east and south were absorbed through cultural expansion, mixing with the Shang until they were indistinguishable. Others, who resisted assimilation into Chinese civilization, tended to move beyond the frontiers, or opposed Shang rule by force. Oracle bone inscriptions offer evidence of extensive military campaigns, but also suggest that diplomacy and intermarriage were frequent instruments of external relations. Defense of the state was the king’s responsibility in the most literal way: he was expected to lead his followers and his allies into battle.

Archeologists have also found evidence of trade between the area controlled by the Shang and other peoples to the south, both coastal and interior. The clay used by potters, the copper and tin used in making bronze implements, the cowrie shells that may have been a form of currency, gold and precious jewels found in ornaments, were all imported. The art historian Sherman Lee has determined that a Shang bronze currently at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco was modeled after an Indian rhinoceros, supporting reports that the Shang maintained a royal zoo containing exotic animals obtained from other regions of Asia.5

The emergence of the Shang state and the exercise of its power forced people on the periphery to organize for their defense. Oracle bones record frequent border skirmishes with the Qing to the west and several major battles with a people called the Guifang, probably nomads to the north. But when the Shang dynasty fell, the attack came from within, from the Zhou, who were members of the Shang state, but sufficiently marginal to constitute a separate core of power by the eleventh century BCE. Less sophisticated than the Shang in civilized refinements, the Zhou expanded aggressively alongside the Shang, formed important alliances with political entities surrounding the Shang, and defeated them in battle at mid-century, approximately 150 years after Achilles and Agamemnon sacked Troy. Building on Shang accomplishments, the Zhou dynasty ruled China, at least nominally, for the next 800 years. Population estimates are necessarily crude, but it is likely that the Xia controlled lands in which the people numbered in the hundreds of thousands, that millions came under Shang dominion, and that by the end of the Zhou dynasty in 221 BCE, China’s population was in the vicinity of fifty to sixty million.

Students of ancient China consider the early or Western Zhou dynasty to be the wellspring of Chinese civilization. Notions of the central kingdom and the universal state had appeared perhaps as early as the Xia era, and certainly under the Shang; but they were articulated most explicitly by the Zhou, who claimed that China was the only state, that its authority extended to all under heaven. Certainly they were aware of others beyond their rule, but such independent status was deemed temporary. Central to the universe was the Zhou state whose management was supervised by heaven. The Zhou developed the concept of the mandate of heaven, of a contractual arrangement between the ruler and the heavenly power, allowing the king to rule only so long as he served the people well. They did so to legitimize their rule, to explain why they had seized power from the Shang.

The Zhou had long been a Shang tributary. They succeeded in overthrowing their powerful overlords by winning allies among groups all around the periphery of the state. Once in control, they adopted Shang material and political culture, winning Shang collaboration as well. The Zhou organized a central bureaucratic administration and maintained a royal army to cope with unrest at home or major barbarian raids on the frontier. On the periphery, relatives and allies of the king were awarded control of local people, becoming feudal lords. Their dominion was over a specific population rather than a territory and they were frequently sent with their people into new areas as military colonists. Initially weak, the feudal lords gradually increased their power at the expense of the center, ultimately reducing the Zhou king to but nominal suzerainty.

MAP 1. ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS, C. 1000 BCE

(After Fairbank and Reischauer, East Asia: The Great Transformation, pp. 10–11).

The Zhou were markedly aggressive and expanded the area of Chinese civilization enormously. Neighboring peoples were conquered and assimilated into the central kingdom. A newly conquered territory would quickly be occupied by a garrison that likely composed the entire populace; led by a Zhou feudal lord, an entire feudal realm moved and became a military colony, overwhelming but not obliterating the local culture, absorbing local collaborators into the political elite. Whether the means of expansion was military or diplomatic, achieved by force or intermarriage, barbarians had the option of assimilation. The success of pacification in the border lands was linked to cultural fusion, to Zhou willingness to accept and integrate local culture and elites rather than impose the Shang-Zhou hybrid found at the center.

After approximately three hundred years of extending its power, the Zhou dynasty overreached itself. As it pressed eastward toward the coastal regions, unassimilated Rong barbarians rose in the west, feudal lords embellished their own powers rather than support the king, and both capital and king fell to the barbarians in 770 BCE. The surviving heir to the throne fled east to a new capital in the vicinity of modern Luoyang and the dynasty survived for more than five additional centuries. Real power, however, had passed to feudal realms that became de facto independent s...