![]()

1

Inauspicious Beginnings (1895–1950)

Images in movement

As the philosopher Gilles Deleuze has argued, the earliest stage of film, epitomized by Auguste and Louis Lumière’s L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (‘Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station’, 1895), was characterized by ‘images in movement’. The ‘cinématographe’ – an early moving image projector to which we owe the word ‘cinema’ itself – was given its first public demonstration by the Lumière brothers in the Grand Café, Paris, on 28 December 1895, when they screened their film. There are reports of the audience running out of the Grand Café in horror when they saw the train approaching. As Paola Marrati suggests:

In the early days of cinema, before the introduction of the mobile camera, the frame was defined in relation to a unique, frontal point of view: the spectator. In this context the shot was a purely spatial determination indicating the distance between the camera and the objects filmed, from the close-up to the long shot. At this stage, these first images produced by the cinema are not by their nature different from those in the theatre, for instance. They are what Deleuze calls images in movement.1

In this ‘primitive cinema’ phase, to use Deleuze’s terminology, film was defined and mediated by the fixed frontal camera which would record objects in real time, rather like a cameraman simply filming some actors on a stage in a theatre. Filming, as a result of being still tied in performance terms to the mechanics of the theatre, sought to amaze audiences with the screening of movement, ranging from the arrival of a train at La Ciotat station as mentioned above, or events such as people leaving a factory or a church, or the moving pictures of sports events. Given the portability of the ‘cinématographe’ – it weighed less than 20 lb (9 kg) – the Lumière brothers sent their cameramen around the world to give demonstrations of their new invention. In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the first screening of what was then called the ‘Omnigrapho’ took place on 8 July 1896 at 57 rua do Ouvidor.2 On 28 July 1896, L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat was screened in the Odeon Theatre in Buenos Aires, and subsequently at the Cinematógrafo Lumière, 9 Plateros Avenue, in Mexico City in August 1896; the cameraman was Gabriel Vayre.3 The first film screenings took place in Lima, Peru, on 2 January 1897 and in Havana, Cuba, on 24 January 1897.4

Film soon developed into the screening of actualities, such as an official function attended by a state dignitary, as well as other newsworthy events. Examples of some of these early actualité-type films in Latin America are Un célebre especialista sacando muelas en el Gran Hotel Europa (‘A Celebrated Specialist Pulling Teeth at the Gran Hotel Europa’, dir. Guillermo and Manuel Trujillo Durán, Venezuela, 1897) and Carrera de bicicletas en el velódromo de Arroyo Seco (‘Bicycle Race at the Arroyo Seco Velodrome’, dir. Félix Oliver, Uruguay, 1898). It was not long, though, before audiences were craving more interesting material than a train arriving at a station or a dentist’s antics. During the Mexican Revolution (1911–19), the flamboyant revolutionary Pancho Villa signed a contract with Mutual Film Corporation for $25,000, giving in exchange permission for the battles he waged to be filmed and broadcast in the United States, even agreeing to have his dawn executions filmed. As he promised the cameraman:

Don’t worry Don Raúl. If you say the light at four in the morning is not right for your little machine, well, no problem. The executions will take place at six. But no later. Afterwards we march and fight. Understand?5

Movement-image

The screening of actualities led – again quite rapidly – to a number of experiments with the new medium of moving images. It was once photographers began to explore different ways of playing back and recombining the recorded images that the seventh art of the silver screen was born: montage. It was arguably with Georges Méliès’ 30-scene, fifteen-minute narrative film Le Voyage dans la lune (‘Journey to the Moon’, 1902) that montage emerged most famously into filmic discourse, notably in the sequence in which the spaceship is depicted landing in the moon’s eye. Though Méliès’ editing was rudimentary it was the first hint of what Deleuze called the creation of ‘movement-images’, of a new sense of narrativity. As Marrati suggests:

In primitive cinema, as in natural perception, movement depends on a body that is displaced through a space that is itself fixed. Movement remains attached to moving bodies; it does not emerge in itself. The emancipation of movement, its appearance in a pure state, so to speak, would come to be one of cinema’s great achievements, but it would only happen progressively, with the introduction of the mobile camera and montage.6

Film in Latin America, as elsewhere in the world, gradually developed from the screening of actualities to the creation of realist narratives. Over time a number of montage techniques were developed, such as film continuity (Edwin S. Porter), cross-cutting (D. W. Griffith) and point-of-view shots (Vitagraph), and this progression from actualities to realist film involved an ‘emancipation of movement’, to use Deleuze’s term, which was expressed specifically as a transition from image-in-movement to movement-image.7 The earliest narrative (movement-image) films were documentaries about famous individuals, such as El fusilamiento de Dorrego (‘Dorrego’s Execution’, dir. Mario Gallo, Argentina, 1908), Paz e amor (‘Peace and Love’, dir. Alberto Botelho, Brazil, 1910), A vida do Cabo João Cândido (‘The Life of Commander João Cândido’, dir. unknown, Brazil, 1910) and Revolución orozquista (‘Pascual Orozco’s Revolution’, dir. Alva brothers, Mexico, 1912).

This group of documentaries was followed by a number of fiction narrative films such as El automóvil gris (‘The Grey Car’, Mexico, 1919), El húsar de la muerte (‘The Hussar of Death’, Chile, 1925), Luis Pardo (Peru, 1927), Brasa dormida (‘Sleeping Ember’, Brazil, 1928), Del pingo al volante (‘From the Country to the Town’, Uruguay, 1929) and La Venus de nácar (‘The Venus of Mother of Pearl’, Venezuela, 1932) which explore montage innovatively and embody the movement-image characteristic of classical-realist cinema as analysed by Deleuze in which the characters are embedded within a situation which has its own momentum. As Deleuze suggests, in classical-realist cinema ‘objects and settings already had a reality of their own, but it was a functional reality, strictly determined by the demands of the situation . . . The situation was, then, directly extended into action and passion’.8 The situations portrayed in realist cinema were subject to sensory-motor schemata which were ‘automatic and pre-established’, articulating a visible cause and effect relationship between the situation and the character’s actions.9 As Deleuze further suggests, ‘The space of a sensory-motor situation is a setting which is already specified and presupposes an action which discloses it, or prompts a reaction which adapts to or modifies it.’10

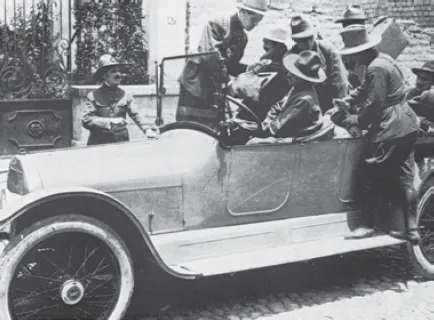

An excellent early example of the movement-image narrative style in Latin America is El automóvil gris, directed by Enrique Rosas, the earliest silent film to emerge from Mexico, first screened in Mexico City on 11 December 1919. The film was originally intended as a documentary about the lives of a group of crooks who were targeting upper-class households in Mexico City in 1915. A local detective, Juan Manuel Cabrera, agreed to have Enrique Rosas follow him in his investigations. Enrique Rosas, however, decided to depart from the original documentarist approach, working with actors to reconstruct the robberies. The film began to reconstruct the scene of the crime, rather like an embryonic version of Crimewatch.

In the first scene we see the gang members swear an oath of allegiance to one another. Then we see a young girl kidnapped off the streets and bundled into the ‘grey car’ that becomes almost the protagonist of the crime. The event is pre-prepared by the creation of cinematic tension; we watch the girl walk past the car and then we see the gang jump out, pounce and bundle her into the car. In the following scene we see the forced entry into a house, the bullying of the women until they reveal where the money and the jewels are, the hurried escape and the sharing-out of the loot. As this first episode demonstrates, El automóvil gris works like a fiction film because it creates tension between interlocking episodes; the divvying-up of the loot is full of tension because the young girl who has been kidnapped is the novia (girlfriend) of one of the members of the gang, and she sees him when she looks through a crack in the door. El automóvil gris has an excellent sense of continuity and dramatic tension; it is an action-based drama more than a piece of journalism. And yet the documentarism of its genesis came back to haunt the film in its closing sequence in which we see the actual criminals – who had been captured and convicted – lined up against a wall and shot dead by firing squad. The film demonstrates the osmotic nature of the medium at this early period in Latin America. Enrique Rosas was director, screenwriter, cameraman and producer. But just as importantly, El automóvil gris demonstrates that the mixture between fiction and documentary was already in the DNA of the Latin American cinematic tradition by 1919. It was a legacy which would prove to be one of the distinctive characteristics of Latin American film.

| The grey car in El automóvil gris (1919). |

Six years later, a very significant silent film was made in Chile, differing from the Mexican film in that it was an excavation of the historical past of that Latin American country. El húsar de la muerte, which premiered on 24 November 1925 in Santiago, was directed by Pedro Sienna. He also starred in the film, which tells the story of the adventures of the guerrilla leader, Manuel Rodríguez (1785–1818), during the Reconquista up until his death in 1818. The 65-minute film was reconstructed in 1962 and 1995 by the film unit at the University of Chile and is now considered a ‘national monument’. Unlike the history books that focus on the liberation of Chile via the figures of José de San Martín and Bernardo O’Higgins, this silent film tells the story via the perspective of the guerrilla leader, Manuel Rodríguez. Though José de San Martín does appear in the film Bernardo O’Higgins is airbrushed out of the frame, perhaps not surprisingly since the two men did not always see eye to eye. (After the Battle of Chacabuco in 1817, for example, won by José de San Martín, O’Higgins ordered Rodríguez’s arrest, and Rodríguez only managed to escape his prison sentence as a result of San Martín’s intervention.)

The film opens with the rout of the Chilean troops by the Spanish army at the Disaster of Rancagua in 1814. While the royalists are celebrating, Rodríguez sends them a message: ‘No alegrarse demasiado. Se acerca la hora de la libertad. Mueran los tiranos ¡Viva la patria!’ (Don’t get too happy. The hour of freedom is approching. Down with tyrants. Long live our motherland!) Rodríguez rallies the Chilean troops, encouraging them to fight a rear-guard action against the Spanish, and he begins to take on various disguises, allowing him to travel around Santiago undisturbed. The royalist captain, Vicente San Bruno, is portrayed as disturbed by this via montage; the captain hangs his head in his hands when he imagines Rodríguez in his various disguises, as presented by some (rudimentary) cross-cutting between the captain’s face and Rodríguez’s different disguises. The film also adds a star-crossed love motif to the plot, having Rodríguez fall in love with the daughter of the Marquis of Aguirre, their union ‘forbidden’ since it cuts across political lines (the Marquis of Aguirre, as his title suggests, is a royalist). Rodríguez’s popularity among the lower classes is suggested by the introduction of a boy guerrillero called ‘El Huacho Pelao’ (The Ragamuffin Soldier) who is so fed up with being bullied by the Spanish troops that he decides to fight for Rodríguez. The film has all the types of ‘errors’ associated with early twentieth-century filmmaking (dialogue intertitles not synchronized with actors’ dialogue, non-adherence to the 180-degre...