- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Landscape has been central to definitions of Englishness for centuries. David Matless argues that landscape has been the site where English visions of the past, present and future have met in debates over questions of national identity, disputes over history and modernity, and ideals of citizenship and the body.

Landscape and Englishness is extensively illustrated and draws on a wide range of material – topographical guides, health manuals, paintings, poetry, architectural polemic, photography, nature guides and novels. This edition contains a new preface by the author.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Landscape and Englishness by David Matless in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Landscape for a New Englishness

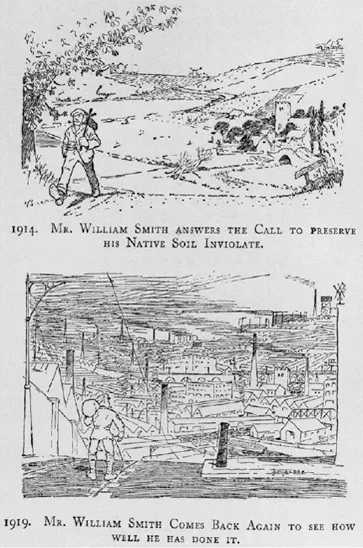

4 Mr William Smith, 1914/1919. Punch cartoon reproduced in C. Williams-Ellis, England and the Octopus (London, 1928).

1

Ordering England

A Crisis of English Landscape

At the front of his 1928 book England and the Octopus Clough Williams-Ellis reproduced a Punch cartoon of war and its aftermath (illus. 4),1 which showed the betrayal of ordinary Mr William Smith and his green and pleasant land. In 1914 he left behind a village world with church and fields and birds, and now he returns to a town of wires and roads and mess. If, as Paul Fussell and others have argued, a sense of Englishness as being essentially rural was the basis for many formulations of national identity in the 1914–18 war,2 the message given here is that the patriot and his landscape have been betrayed by vested interest.

Williams-Ellis diagnosed a crisis in the post-war English landscape: ‘There are such things as “Dangerous Ages”, and the most dangerous ages are those at which the normal rate of change is most abnormally accelerated … we are surely living more dangerously now than at any time.’3 England and the Octopus promoted the message of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, set up in 1926 largely through the initiative of planner Patrick Abercrombie. The book was recently republished by the CPRE in celebration of their seventieth anniversary. Concern for the English landscape was not new in 1926; the National Trust had been campaigning since 1895, the Commons Preservation Society since 1865, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings since 1877, the Society for Checking the Abuses of Public Advertising since 1893. The CPRE was distinctive, though, in seeking a complete coverage of rural landscape through the co-ordination of the efforts of groups concerned with specific issues of architecture, planning, landowning, leisure, local government and wildlife. At first sight, the kind of William Smith imagery used by Williams-Ellis might suggest a movement for the old against the new, for country against city, for tradition against the modern. However, while the CPRE was not averse to rural elegy, the argument of this chapter is that this movement for preservation entailed not a conservative protection of the old against the new but an attempt to plan a landscape simultaneously modern and traditional under the guidance of an expert public authority. We will consider in turn the modes of authority and government cultivated by this movement, the order of settlement it envisaged, and the modern content of its English landscapes.4

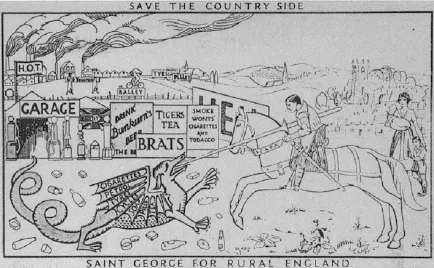

A sense of the preservationists’ self-belief and presumed authority can be gained from considering the typical form of their arguments, namely binary contrasts of good and evil, order and chaos, beauty and horror, which are routinely deployed so as to make preservation appear a matter of national fundamentals. This language is not simply polemical excess. Preservationists use binary absolutes in their statements both to raise the stakes and claim a clear and absolute authority over landscape. Preservationist discourse becomes locked in dichotomy, with a diagnosis of disorder and a will to order feeding off one another. This binary rhetoric was most clearly expressed in photographs contrasting before and after, of what is with what might be. Publications and exhibitions sought to encourage anger. A ‘Save the Countryside’ exhibition, initially set up alongside the first Countryside and Footpaths Preservation National Conference in Leicester in October 1928, travelled around the country and later went to Belgium and America: ‘The show brings home to people in the most vivid manner the desecration that is taking place, and contrasts the debasement of rural scenery with unspoilt examples.’5 The exhibition was set up by Harry Peach, head of the CPRE’s Exhibitions Committee. Peach owned the successful Leicester-based Dryad Handicrafts firm, and was prominent in the Design and Industries Association (DIA), producers of ‘Cautionary Guide’ books on town disfigurement for St Albans, Oxford and Carlisle. Their 1929–30 yearbook, The Face of the Land, edited by Peach and Noel Carrington, drew heavily on CPRE exhibition material.6 Display boards in the show contrasted good and bad, before and after, beautiful and ugly, good and evil, order and disorder, basic oppositions suggesting the unquestioning authority of the preservationist. We shall see below how this way of thinking mirrored the aesthetic of clarity and harmony on display; minds, as well as landscapes, should be tidy. Accompanying postcards reiterated a fundamental patriotic authority. ‘Saint George for Rural England’ (illus. 5) set the patron saint against a dragon of laissez-faire commercial culture: motoring, garages, smoke, advertisements, litter. On one side the dragon, on the other Saint George, riding over a foreground of natural rather than human litter, defending the nucleated village and the nuclear family. Precise, composed and triumphant, Saint George stands for a certain England, for a gentle force of order, for the preservationists’ sure categories of judgement.

5 ‘Save the Countryside: Saint George for Rural England’. Postcard issued by the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, 1928.

My argument is that this judgement is a distinctly modern one. That is not to deny that within the broad preservation movement there were archly anti-modern, traditionalist voices, but I would suggest that the dominant voices were those committed to planning and designing a new England. In his 1938 Penguin Special on Design, Anthony Bertram asserted the modernity of this preservation: ‘there is a grossly unfair tendency to mix up the CPRE with the sort of arid conservatism which tries to mummify the countryside, which automatically opposes all innovations, all new design, all demolition and reconstruction. If any such people hide under the cloak of the CPRE, they have certainly no right to be there.’7 It was this openness to modern design and reconstruction which enabled preservationist planning to achieve a position of cultural and political power during and after the Second World War; we will now consider the ways in which the interwar preservationist movement was formed through particular assumptions regarding the role of the state and the possibilities of the plan.

Englishness and Government

If a future England was to be planned, the question was, who would plan, and how? Preservation was a call for government which appeared to question prevailing modes of governance for their lack of control over the country. Discussions of preservation have tended to focus on the detail of what was to be preserved rather than setting the argument within the broader field of authority and governance. Here we highlight how the preservation movement constituted itself by connecting Englishness and government in such a way as to challenge private rights and restyle public authority.

Preservationists argued that in the nineteenth century an attitude of laissez faire had destroyed the town, and in the twentieth century was destroying the country. In Williams-Ellis’s collection Britain and the Beast J. M. Keynes described the Victorian ‘utilitarian and economic … ideal’ as the ‘most dreadful heresy, perhaps, which has ever gained the ear of a civilised people’.8 For Williams-Ellis it was a matter of ‘Laissez Faire or Government’: ‘the choice lies between the end of laissez faire and the end of rural England.’9 In questioning the rights of private property – ‘we have definitely begun to realize that to go as you please is no way to arrive at what is pleasant, and that private rights are no longer defensible when they result in public wrongs’10 – Williams-Ellis claimed the voice of the nation:

Discipline! How unwilling we English are to submit to even a little of it … But we do in the end submit; we did in the War and we shall do so yet again in this matter of preserving England … In this matter, I say, we are petitioning to be governed; we ask for control, for discipline. We have tried freedom and, under present conditions, we see that it leads to waste, inefficiency, and chaos.11

Preservationists offered their expertise as a means to national preservation.

There were tensions, however, in asserting the public over the private. Preservationists trusted neither the general public (as we shall see in Chapter Two) nor their elected officials: ‘What constructive contribution can the average town-councillor … make? It is obviously unfair to ask him to make any. This is no routine matter like cleaning streets or erecting urinals. What hope can there be here of enlightened authority?’12 Wary of the current constitution of public authority, preservationists were cautious of proposing control via public ownership of land. A delicate balancing act occurs whereby ‘responsible’ private ownership is upheld and a role for the state fashioned which follows landowning etiquette through the metaphor of the nation estate. Abercrombie lamented ‘rural disintegration’:

If the country had remained in the hands of the same families who have done so much to create its typical English beauty in the past … the greater use of the country … might have been directed into more defined areas …, the bulk of the normal country remaining unchanged … The former guardians of the country are no longer in possession.

Preservationists map distinctions of good and bad ownership onto distinctions of old and new money, the former supposedly willing to submit to regulation out of love of the land and a sense of national duty,13 the latter likely to be in cahoots with ‘a new trade … the land butcher – a personage entirely ruthless and untrammeled by traditions’ and developing land ‘in the most brutal manner … daring a feeble authority to control his efforts’.14 Yet, however fond the regard for old owners, property is held to be unable to guarantee the landscape any longer; the general trajectory of history is seen as heading towards public authority: ‘the landlords are disappearing and the practical problem is, how to order and regulate the break-up of their estates.’15 The solution might be to manage England as one nation estate:

The government of a country has this essential continuity, and with it power and authority delegated to it by the governed. When the property in trust is a Kingdom, and the beneficiaries a whole people, the proper trustee would seem to be the State, the conservation of a nation’s assets and their protection from a spendthrift squandering in our present time being surely matters within the proper function of a Government.16

Preservationist geographer Vaughan Cornish mused that ‘if England were one man’s freehold’, regulation ‘would be a simple matter’.17 The estate anal...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Passport to Plenty: Preface to the 2016 Edition

- Introduction: Versions of Landscape and Englishness

- PART I: LANDSCAPE FOR A NEW ENGLISHNESS

- PART II: ORGANIC ENGLAND

- PART III: LANDSCAPES OF WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION

- PART IV: FESTIVALS AND REALIGNMENTS

- REFERENCES

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS FOR THE 1998 EDITION

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS FOR THE 2016 EDITION

- PHOTOGRAPHIC ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INDEX