![]()

1 Making Margins

The men of the Middle Ages participated in two lives: the official and the carnival life. Two aspects of the world, the serious and the laughing aspect, co-existed in their consciousness. This co-existence was strikingly reflected in thirteenth and fourteenth-century illuminated manuscripts . . . Here we find on the same page strictly pious illustrations . . . as well as free designs not connected with the story. The free designs represent chimeras (fantastic forms combining human, animal and vegetable elements), comic devils, jugglers performing acrobatic tricks, masquerade figures, and parodical scenes – that is, purely grotesque carnivalesque themes . . . However, in medieval art a strict dividing line is drawn between the pious and the grotesque; they exist side by side but never merge.1

Opening her Book of Hours at Terce, the third canonical Hour of the day, which was at about 9 o’clock in the morning, a woman – who was possibly called Marguerite and who lived in the second quarter of the fourteenth century – would have seen herself on the ‘dividing line’ in the margin of the left-hand page (illus. 14). Holding open a tiny book – this book – she kneels before the Adoration of the Magi that takes place under the triple arches of a Gothic shrine built into the letter ‘D’ of God’s Word, Deus. Looking down to the bas-de-page, she would have seen how three monkeys ape the gestures of the wise men above. Top left, a spiky-winged ape-angel grasps the tail of the ‘D’, as if he is about to pull the string that will unravel it all. Another simian plays a more supportive role, holding aloft, Atlas-like, the platform on which she kneels. On the sinister, or left side, and also mocking the gift-bearing Magi, struts a marvellous monster, known as a sciapod because of his one enormous foot, who proffers a golden crown.

The opening words, Deus in audiutor (O Lord hear my prayer), remind us that the owner of this book would have read it out loud. But would her prayers not have been interrupted by the visual noise of bells clanging from the Fool’s Cap of a glaring gryllus at the top right, or the din of the pipe and tabor at the lower limit? These pages of Marguerite’s Hours, rather than revealing her participation in what the Russian scholar Mikhail Bakhtin described as two distinct aspects of medieval life – one sacred and the other profane – situate her neither outside nor inside, but in-between, on the edge.

The butterfly juxtaposed with a cooking-pot in the right margin of the opposite page might remind modern observers of the Surrealists’ pleasure in the ‘fortuitous meeting of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table’. But whereas modern artists such as Magritte or Ernst juxtaposed banal fragments of the real world as ominous fetishes, the exquisite incongruity of medieval marginal art refuses us the illusion of a dream. These combinations are as conscious and as instrumental as the little monsters that bleep and zig-zag across today’s computer screens in similar games of scopic concentration. Other words that, like ‘surreal’, are inappropriate for describing these creatures include the Romantic term ‘fantastic’ (as used in Jurgis Baltrusaitis’s book Le Gothique fantastique, 1960), and – most important of all – the negatively loaded term ‘grotesque’, which was invented in the sixteenth century to describe newly discovered Antique wall paintings.2 Marguerite might have described her marginal creatures with the Latin terms fabula or curiositates, but this laywoman would more likely have used a variant of the term babuini (the source of our word baboon), which is recorded in a document of 1344 describing carvings by a French artist at Avignon, and which might best be translated as ‘monkey-business’.3 Chaucer used the word in English when describing a building decorated with ‘subtil compasinges, pinnacles and babewyns’, making a double reference to simian similarity – babewyn, or baboon-like, and compassinge, which joins the word for geometrical design with singe or monkey.4

That the term babewyn came to stand for all such composite creatures, and not just apes, is significant. Isidore of Seville, the authority on etymology throughout the Middle Ages, traced the derivation of simius, or ape, from similitudo, noting that ‘the monkey wants to mimic everything he sees done’.5 A beast that was kept as an entertaining toy by jongleurs and as a pet by the nobility, the ape came to signify the dubious status of representation itself, le singe being an anagram for le signe – the sign. The prevalence of apes in marginal art similarly (sic) draws attention to the danger of mimesis or illusion in God’s created scheme of things.

Marguerite might also have called the things in the margins fatrasies, from fatras, meaning trash or rubbish, which was a genre of humorous poetry particular to the Franco-Flemish region where her Book of Hours was produced. Although they follow a strictly syllabic form, these poems describe things that might have sprung from its very pages:

D’un pet de suiron

Uns pez se fist pendre

Por l’i miex deffendre

Derier un luiton;

La s’en esmervilla on

Que tantost vint l’ame prendre

La teste d’un porion . . .

From the foot of a mite a fart hung himself, the better to hide behind a goblin; whereupon all were astounded, for there, to carry off his soul, came the head of a pumpkin.6

The fatrasie, which consist of communications that are impossible despite the comprehensibility of each linguistic unit, are not unlike that which we see in the margins. These poems are, however, perfectly self-contained, and they were enjoyed by court society as an amusement, whereas the systematic incoherence of marginal art is placed within, perhaps even against, another discourse – the Word of God. Yet, what we today may perceive as contradictory cultural codes might not have been seen as so separated during the Middle Ages. In a typical non-illustrated manuscript (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fr. 19152) we can find moral tales, saints’ lives, fables, courtly poems and two bawdy fabliaux bound together. The concoction of hybrids, mingling different registers and genres, seems to have been both a verbal and a visual fashion for élite audiences. Monkey-business, such as that to be seen in Marguerite’s Hours, can be found in the borders of contemporary stained-glass windows at York Minster, documented in liturgical albs made for Westminster Abbey and embroidered on the cushions made for the private chapel of Isabella of Hainault, the Flemish consort of Edward III.7 But this still does not answer the question of what it was that such elevated patrons wanted in this garbage-world, this apish, reeling and drunken discourse that filled the margins of their otherwise scrupulously organized lives.

THE WORLD AT THE EDGES OF THE WORD

People’s fears were exorcised by dumping them on those who inhabited the edges of the known world, who were lesser in some sense; whether troglodites or pygmies . . . the outskirts are felt to be infected zones, where all kinds of monstrosities are possible, and where a different man is born, an aberrant from the prototype who inhabits the center of things.8

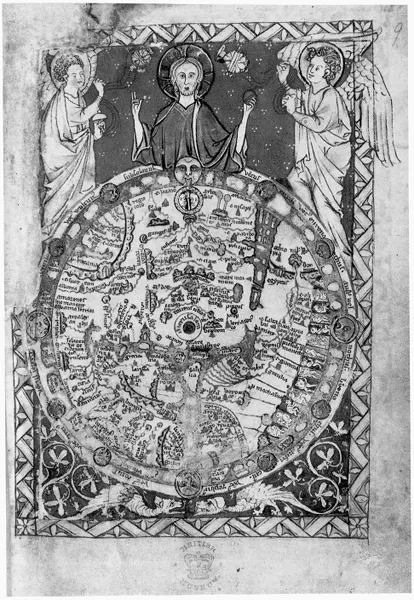

During the Middle Ages the edges of the known world were at the same time the limits of representation. On the World Map painted on a page of an English Psalter of c. 1260 (illus. 2), the further one moves away from the centre-point of Jerusalem, the more deformed and alien things become. From outside time and space, in the apex of the page, God controls all, while two coiled dragons suggest the space of the ‘underworld’ at the bottom. Skirting Africa in the lower-right quadrant of this tiny one-and-a-half-inch cosmos, the artist has managed to depict fourteen of the monstrous races whose types derive from Pliny and who were thought to exist ‘at the round earth’s imagined corners’.9 Here we see minute blemyae and cynocephali (men with eyes in their chests and dog-headed persons), giants, pygmies and many others. There is a sciapod too, like the one who must have come a long way to play a mock-magus in the left margin of Marguerite’s Hours. In this sense, illuminators were often not inventing monsters but depicting creatures they might well have assumed existed at the limits of God’s creation.

With God at the centre of the medieval panopticon, ‘all-seeing’ and everywhere at once, most models of the cosmos, society and even literary style, were circular and centripetal. The safe symbolic spaces of hearth, village or city were starkly contrasted with the dangerous territories outside, of forest, desert and marsh. Every country child would remember the boundary brooks and trees where he was dunked and bumped on Rogation Day in a village ritual sometimes called Beating the Bounds, which marked upon his own body the spatial limits of his world. The realms of the unknown were not distant continents traversed by travellers and pilgrims; they began just over the hill.

2 World map. Psalter. British Library, London

Yet people were also highly sensitive to disorder and displacement precisely because they were so concerned with the hierarchy that defined their position in the universe. Such schémas included, in addition to the three orders of society – those who prayed, fought and laboured – the free and unfree, religious people and lay, city-dwellers and country-dwellers, and, of course, women and men. Although it lacked our predominant dichotomy of public versus private, the medieval organization of space was no less territorial. In the fields, strips marked off each peasant’s holding, while in towns and cities every street and enclave, each market and waterway, came under the control of particular ecclesiastical or secular lords. The thirteenth century was precisely the period of arable expansion that reclaimed much marginal land for enclosure to increase seignorial revenues.10 This control and codification of space represented by the labelled territories of the centrifugal circular World Map created, of necessity, a space for ejecting the undesirable – the banished, outlawed, leprous, scabrous outcasts of society.11

If these edges were dangerous, they were also powerful places. In folklore, betwixt and between are important zones of transformation. The edge of the water was where wisdom revealed itself; spirits were banished to the spaceless places ‘between the froth and the water’ or ‘betwixt the bark and the tree’. Similarly, temporal junctures between winter and summer, or between night and day, were dangerous moments of intersection with the Otherworld. In charms and riddles, things that were neither this nor that bore, in their defiance of classification, strong magic. Openings, entrances and doorways, both of buildings and the human body (in one Middle English medical text there is mention of a medicine corroding ‘the margynes of the skynne’), were especially important liminal zones that had to be protected.

Most of the visual art that has come down to us from the early Middle Ages was made for God. All else was the Devil’s. In a letter written to the Archbishop of Canterbury in 745, St Boniface complained of

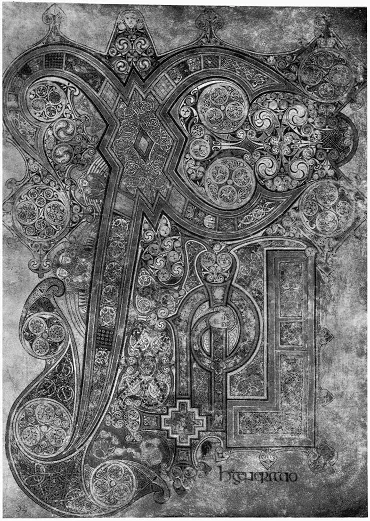

3 ‘Chi-Rho’ monogram. The Book of Kells. Trinity College, Dublin | |

those ornaments shaped like worms, teeming on the borders of ecclesiastical vestments; they announce Antichrist and are introduced by his guile and through his ministers in the monasteries to induce lechery, depravity, shameful...