- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The End of Illness

About this book

Can we live robustly until our last breath?

Do we have to suffer from debilitating conditions and sickness? Is it possible to add more vibrant years to our lives? In the #1 New York Times bestselling The End of Illness, Dr. David Agus tackles these fundamental questions and dismantles misperceptions about what “health” really means. Presenting an eye-opening picture of the human body and all the ways it works—and fails—Dr. Agus shows us how a new perspective on our individual health will allow us to achieve a long, vigorous life.

Offering insights and access to powerful new technologies that promise to transform medicine, Dr. Agus emphasizes his belief that there is no “right” answer, no master guide that is “one size fits all.” Each one of us must get to know our bodies in uniquely personal ways, and he shows us exactly how to do that. A bold call for all of us to become our own personal health advocates, The End of Illness is a moving departure from orthodox thinking.

Do we have to suffer from debilitating conditions and sickness? Is it possible to add more vibrant years to our lives? In the #1 New York Times bestselling The End of Illness, Dr. David Agus tackles these fundamental questions and dismantles misperceptions about what “health” really means. Presenting an eye-opening picture of the human body and all the ways it works—and fails—Dr. Agus shows us how a new perspective on our individual health will allow us to achieve a long, vigorous life.

Offering insights and access to powerful new technologies that promise to transform medicine, Dr. Agus emphasizes his belief that there is no “right” answer, no master guide that is “one size fits all.” Each one of us must get to know our bodies in uniquely personal ways, and he shows us exactly how to do that. A bold call for all of us to become our own personal health advocates, The End of Illness is a moving departure from orthodox thinking.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The End of Illness by David B. Agus in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Alternative & Complementary Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Science and Art of Defining Your Health

If I had to sum up this entire book in a single phrase, it would be this: get to know yourself. I don’t mean that in a cosmic or purely psychological way. I’m a big believer in what’s called personalized medicine, which refers to customizing your health care to your specific needs based on your physiology, genetics, value system, and unique conditions. We are finally entering an exciting time in medicine where we have the technology to custom-tailor treatment and preventive protocols just as we’d custom-tailor a suit or designer gown to one’s individual body. But it all begins with you. You have to know yourself in a manner that you’ve probably never done before.

Right now, most of us live by sweeping, general guidelines that are one-size-fits-all. If you want to lose weight, for example, you pick a diet that’s marketed to everyone and which likely recommends that you eat more fibrous vegetables and cut back on processed sugar. If you want to reduce your risk for cancer, you’ll be told to avoid tobacco smoke, to exercise regularly, and to take early detection seriously. But imagine being able to have a more explicit oracle into your future health, as well as a more exacting set of rules to follow today. Think about what it would be like, for instance, to know precisely how to tweak your diet to effortlessly lose twenty pounds for good, or to have a detailed list of things to avoid and things to embrace that make you feel fantastic and be in tip-top shape, or to know what the perfect amount of medicine X is for you to combat affliction Y successfully with no side effects. That’s the promise that personalized medicine has to offer.

But, once again, you won’t be able to enjoy the benefits of personalized medicine until you get up close and personal with yourself. Nothing about health is one-size-fits-all, so until you know how to perform your own “fitting,” you won’t be able to live the long and happy life that’s awaiting you.

The checklist below used to be buried deep in the book somewhere—long after I’d done a lot of explaining and storytelling—but I’ve since plucked it out and placed it here. I want to give you a first step in the right direction before I spend a couple hundred pages fleshing out all of my recommendations in detail. This questionnaire was originally designed to help you prepare for a checkup with your doctor, giving you clues to discuss during your visit. However, while piecing this book together, I realized that the same questionnaire should be filled out before even reading the book, which will help you to know yourself better before embarking on this adventure. I also know that you want to be told what to do as soon as possible, and even though you’ll find lots of “health rules” to consider throughout this book, many of which will be called out at the ends of chapters, at least the following questions will equip you with concepts to think about as you read further and incorporate my advice into your life. This questionnaire is also downloadable online at www.TheEndofIllness.com/questionnaire, where you’ll find a version that you can respond to directly on the page to print for your records and/or take to your doctor.

Unlike other self-tests you find in books and magazines, this one doesn’t have a scorecard at the end. Your answers are your own. Once you’ve incorporated some of my forthcoming suggestions, come back to this questionnaire to check in with yourself whenever you want. See how you change from month to month and year to year. Continue to ask yourself, am I as healthy as I want to be?

Part I is all about defining your health, and I’ll begin by taking you on a tour of how we’ve lost our compass with respect to understanding the human body. I’ll reveal a new perspective that gives us a more accurate compass, and then I’ll help you to use that compass in your journey to optimize your health with the technology we have today. At the end of Part I, I’ll share one of the most powerful medical technologies currently in development that will soon allow each of us to personalize our medicine in a truly sophisticated manner. Knowing about this technology now will give you hope for the future, as well as add context to the information in the rest of the book.

1

What Is Health?

A New Definition That Changes Everything

Everyone has a vague idea of what it means to live a healthy life. Eating a balanced diet: good. Smoking: bad. Breaking a sweat regularly: good. Binge drinking: bad. Getting a restful night’s sleep: bonus. Being happy: double bonus. Some of us may choose to disregard these basic tenets on occasion, but for the most part, we know the difference between the habits that help us stay youthful and strong, and those that can detract from our well-being.

We try our best to stay out of harm’s way, but what happens when we get sick or develop a chronic medical condition or, heaven forbid, are diagnosed with a serious illness? After experiencing the frustration of Why me? many of us begin to ask ourselves other, more probing inquiries about where we might have gone wrong. Was it something in the water? A lifelong love of hamburgers and fries? An overdemanding boss and, as a result, an overwhelming stress level? Too much alcohol? Too little exercise? Secondhand smoke? Exposure to industrial chemicals? A habit of living dangerously, whatever that might mean? Bad luck?

Or perhaps, some of us think, this outcome was fated because it was just in my DNA all along.

If I could collect a nickel for every time someone in the world thought that genetics was wholly to blame for this illness or that defect, I’d be the wealthiest man on earth. It’s human nature to point fingers at someone or something else for our flaws and shortcomings, and to avoid any personal culpability. Because DNA tends to be a relatively abstract construct, much like black holes or quarks, which we cannot touch, see, or feel, it might as well be a “something else” to which we can assign guilt. After all, DNA is “given” to us by our parents and we have no choice. In this regard, DNA is practically accidental; just as accidents happen, so does DNA, without our having much say in the matter.

What most people don’t think about, though, is that DNA says more about our risk than our fate. It governs probabilities, not necessarily destinies. As my friend and colleague Danny Hillis (whom we’ll meet later when I cover emerging technologies) likes to describe it, DNA is simply a list of parts or ingredients rather than a complete manual that explains how those parts work together to generate results. To hold your DNA responsible for your health is missing the forest for the trees. It’s not the pièce de résistance. I say this knowing full well that DNA does hold certain keys to your health; if it didn’t, then I wouldn’t have cofounded a company that performs genetic testing so you can take preventive measures based on your genomic risk profile. But right from the get-go I want to entice you to start thinking from a broader perspective that goes far beyond your genes. I want you to view your body—from the outer stretches of your skin to the inner sanctum of your cellular makeup—as a whole system. It’s a uniquely organized and highly functioning system that leaves so much to the imagination because we’re only just beginning to solve its riddles.

So therefore, as we probe the mystery of the human body more deeply, we discover that this system, and its complex riddles, don’t necessarily hinge on DNA alone.

The Inescapable Statistics

To understand how we’ve arrived at a place where we focus so much on DNA, and why it’s critical to respect the body as an elaborate system beyond genetics, it helps to explore the evolution of our thinking processes against the backdrop of the challenges we’ve faced—and continue to face—in our quest for health and longevity.

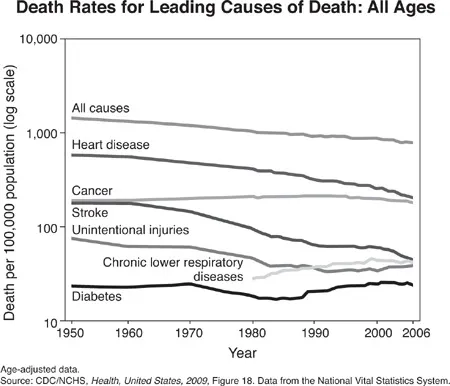

Most of our transformative breakthroughs in medicine have occurred only recently, in the last sixty or so years. Following the discovery of penicillin in 1928, which changed the whole landscape of fighting infections based on the knowledge that they were caused by bacteria, we got good at extending our lives by several years and, in many cases, decades. This was made possible through a constellation of contributing circumstances, including a decline in cigarette smoking, changes in our diets for the better, improvements in diagnostics and medical care, and of course advancements in targeted therapies and drugs such as cholesterol-lowering statins.

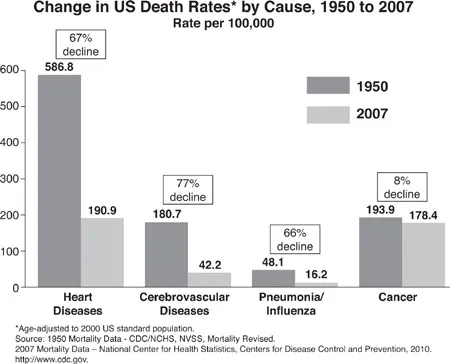

Heart disease has been the leading cause of death in the United States since 1921, and stroke has been the third-leading cause since 1938; together, these vascular diseases account for approximately 40 percent of all deaths. Since 1950, however, age-adjusted death rates from cardiovascular disease have declined 60 to 70 percent, representing one of the most important public health achievements of the twentieth century.

Put another way:

But here’s the sobering truth sitting on the sidelines of these triumphs like a lumbering white elephant: the death rate from cancer from 1950 to 2007 (the most current data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) didn’t change much. We are making enormous progress against other chronic diseases, but little against cancer. Indeed, there are little wins here and there with unique types of cancer. Take, for instance, chronic myelogenous leukemia, a rare type of leukemia that had previously been a death sentence except for a small number of patients who benefited from bone-marrow transplantation. With the FDA approval of Gleevec (brand name for imatinib mesylate) in May 2001—the same month it made the cover of Time magazine as the “magic bullet” to cure cancer—we now have a way to successfully treat most patients and achieve remarkable recovery rates. The drug targets the particular chromosomal rearrangement that is present in this disease (part of chromosome 9 is fused to part of chromosome 22). In clinical trials, the response rate to Gleevec was over 90 percent. People went from their deathbeds to functional life after taking this small molecule with few side effects. But with the more common deadly cancers, including those that ravage...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Foreword to the Revised Edition

- Introduction: Notes from the Edge

- Part I: The Science and Art of Defining Your Health

- Part II: The Elements of Healthy Style

- Part III: The Future You

- Conclusion: Of Mice and Men and the Search for the Master Switch

- Epilogue: Q&A

- Acknowledgments

- Recommended Reading

- About the Author

- Index

- Copyright