eBook - ePub

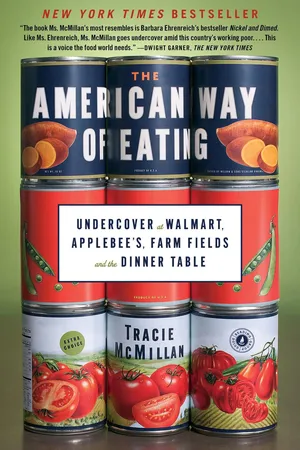

The American Way of Eating

Undercover at Walmart, Applebee's, Farm Fields and the Dinner Table

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The American Way of Eating

Undercover at Walmart, Applebee's, Farm Fields and the Dinner Table

About this book

The New York Times bestselling work of undercover journalism in the tradition of Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed that fully investigates our food system to explain what keeps Americans from eating well—and what we can do about it.

When award-winning (and working-class) journalist Tracie McMillan saw foodies swooning over $9 organic tomatoes, she couldn’t help but wonder: What about the rest of us? Why do working Americans eat the way we do? And what can we do to change it? To find out, McMillan went undercover in three jobs that feed America, living and eating off her wages in each. Reporting from California fields, a Walmart produce aisle outside of Detroit, and the kitchen of a New York City Applebee’s, McMillan examines the reality of our country’s food industry in this “clear and essential” (The Boston Globe) work of reportage. Chronicling her own experience and that of the Mexican garlic crews, Midwestern produce managers, and Caribbean line cooks with whom she works, McMillan goes beyond the food on her plate to explore the national priorities that put it there.

Fearlessly reported and beautifully written, The American Way of Eating goes beyond statistics and culture wars to deliver a book that is fiercely honest, strikingly intelligent, and compulsively readable. In making the simple case that—city or country, rich or poor—everyone wants good food, McMillan guarantees that talking about dinner will never be the same again.

When award-winning (and working-class) journalist Tracie McMillan saw foodies swooning over $9 organic tomatoes, she couldn’t help but wonder: What about the rest of us? Why do working Americans eat the way we do? And what can we do to change it? To find out, McMillan went undercover in three jobs that feed America, living and eating off her wages in each. Reporting from California fields, a Walmart produce aisle outside of Detroit, and the kitchen of a New York City Applebee’s, McMillan examines the reality of our country’s food industry in this “clear and essential” (The Boston Globe) work of reportage. Chronicling her own experience and that of the Mexican garlic crews, Midwestern produce managers, and Caribbean line cooks with whom she works, McMillan goes beyond the food on her plate to explore the national priorities that put it there.

Fearlessly reported and beautifully written, The American Way of Eating goes beyond statistics and culture wars to deliver a book that is fiercely honest, strikingly intelligent, and compulsively readable. In making the simple case that—city or country, rich or poor—everyone wants good food, McMillan guarantees that talking about dinner will never be the same again.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The American Way of Eating by Tracie McMillan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Agricultural Public Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

FARMING

WAGES

Hourly, weeding and gleaning: $8.00

Per 20-pound flat of grapes: $2.00

Per 5 gallons of garlic: $1.60

Per 20-pound flat of grapes: $2.00

Per 5 gallons of garlic: $1.60

POST-TAX INCOME

Weekly: $204

Annually: $10,588

FOOD BILL

Daily: $7.44

Weekly: $52.06

Annually: $2,707

PERCENTAGE OF INCOME SPENT ON FOOD

All food: 25.6%

Food at home: 11.8%

Eating out: 13.8%

CHAPTER 1

Grapes

By the time I meet Pilar, I’ve already spent a week looking for work, venturing out in increasing radii from the cheap hotel where I’ve holed up in Bakersfield. I’ve met with an organizer from the United Farmworkers, outside a rural gas station, to get the phone numbers of foremen. I’ve met with a community advocate, Felix, whose job entails helping farmworkers in one of the farm towns outside the city: recouping back wages, finding health care, and otherwise negotiating rural poverty. I’ve driven up and down the highway looking for onion crews to no avail, hindered by my ignorance of, in descending order, what an onion field looks like, how many people might be on a crew, and basic local geography. In every instance, I have been unable to find work in the fields of California’s Central Valley. Accordingly, I’ve begun to feel the first strains of desperation that precede failure.

Pilar lives in the dusty trailer next door to the one I move into after a week in a hotel. I meet her in exactly the manner that had been suggested to me by Felix: I walk out my front door, go to the nearest trailer, and say hello.

When I come up to the yard, it’s not Pilar but Alejandro, with whom she shares two children, who greets me. He and a boy are talking in the driveway, a narrow spit of gravel that leads to a black pickup, a grove of clotheslines, and, finally, a chain-link fence thick with vines. Beyond it lies another street of trailers holding the line against endless fields of grapes and almonds, and thirty miles beyond that a hot sun lowers itself toward the mountains at the valley’s edge. Near the pickup, a diminutive woman paces under scraggly trees, a cordless phone clutched to her head. Her hair, knotted on her head in a series of loops, looks impossibly long.

Hi! I say, in Spanish, over the fence at the edge of their yard. I wave. I smile. The woman doesn’t notice me, but Alejandro and the boy look up. I smile harder.

I’m Tracie. Alejandro looks startled by my Spanish, but recovers quickly and introduces himself and his son, Sergio. We begin conversing in Spanish. I explain that I am staying in the trailer next door, and when they nod as if this is reasonable, I add that I am looking for work in the fields and need to find a job quickly.

Alejandro raises his eyebrows and tells me his wife is a mayordoma, a forewoman, in grapes.

I try to maintain a measured voice. Does she need workers?

He nods, and dispatches Sergio to bring Pilar over. Sergio tugs at her arm, and she lowers the phone to listen to him. Then she looks at me and promptly bursts into laughter. She comes over.

You want to work in the fields?

Pilar looks at me over the fence, her eyes friendly but baffled. I try to smile naturally, as if there must be many white girls speaking stilted Spanish looking for work in California fields alongside indigenous Mexican immigrants. Then I try to project an air of economic desperation. Yes, I am looking for work in the fields. Do you need workers?

She pauses and looks me up and down again. Why don’t you apply for a job?

I shake my head, taking this to mean applying for a job in a store or an office. I don’t want to have to talk to people. I have a lot of problems right now, and I just want to work hard and not think.

Today is a Sunday, the only day most farmworkers here have off, so the park and its forty-odd trailers buzz with small-town activity. Mexican banda and ranchera music float down the street, mixed with hip-hop in Spanish; families are cooking meat and warming tortillas over heavy metal grills in their yards; little kids are playing soccer in the street, using speed bumps for goals.

I smile sheepishly and repeat my story over the low din behind me: No, I want to work in the fields. I need to work hard so I don’t have to think.

OK, says Pilar. I will have work the day after tomorrow or the day after that. Do you have scissors?

I shake my head.

I can loan you some. Do you have gloves?

Yes!

What kind? Cotton or leather?

Leather.

Pilar shakes her head as if scolding a silly child. I’ll give you some cotton ones. Talk to me tomorrow, when I’ll know if there is work.

Thank you very much! I say, smiling, punch drunk on my luck. Thank you! This is great. I will talk to you tomorrow.

You’re going to have to bring lunch, she adds firmly. Then her tone softens: And we’re neighbors—let us know if you need anything.

Of course, you too, I say as I begin walking back home. Then Sergio calls out.

Wait! he says, in English. She wants to ask you something.

I turn back, and Pilar smiles shyly. Maybe you can help me with my English?

Of course! I’m not a teacher, but I can try to help. She smiles broadly, and we make plans to study the next night.

I say my goodbyes and float home, buoyed by the fact that I have not only just found farmwork but maybe friends, too.

My world, and thus my sources of food, now consists of three municipalities and the trailer park. My trailer is in a tiny rural town whose commercial tenants are limited to an intersection with a concrete block of a corner grocery, a taquería, and a gas station. Ten minutes away sits a slightly larger town, this one with a single main street, two strip malls, and a larger grocery store. Forty minutes past the town is Bakersfield, a city with a university, courthouses, a swath of corporate farm offices and a range of supermarkets. Before I moved to the trailer, Maria Vasquez, the paralegal whose parents have loaned me their trailer while visiting family in Mexico, offered me advice: Go grocery shopping in Bakersfield, at Foods Maxx.

So on my way out of town, I stopped at the discount grocer, which resembled a Mexican-themed Costco. My flour, bread, eggs, cilantro, tomatillos, tomatoes, peaches, lemons, and limes came to $10.34. The Vasquez family also left me some squash and watermelon, a basket of onions, and a half-full five-gallon jug of drinking water.5

From the outside, the trailer nearly resembles a house, with the carport and back porch on the north side and an addition and porch on the south. Its exterior is two-tone orange and white, the facilities basic. There’s a narrow galley kitchen, a combination living/dining room that holds the refrigerator. There are three bedrooms and a large, clean bathroom that would be unremarkable except that the toilet tank is covered by a scrap of plywood and the floor buckles slightly under my weight. Some of the windows don’t quite fit their frames, the back door sits high enough over the threshold that beetles scurry inside at will, and all the locks are flimsy, but I remind myself that a farmworkers’ trailer park would be a poorly chosen target for robbery.

I turn on the swamp cooler to fight the heat that’s baking the roof and soak some beans while I make a green salsa. I’ve only recently started cooking Latin American food, and this salsa is a simple one that I cribbed from a woman I lived with in Guatemala while studying Spanish; I had been thrilled by her tangy version and begged for the recipe, though “recipe” is overstating it—there was no card or cookbook, just the mixture she’d been throwing together forever.

While the beans soak, I sort through my handmade vocabulary cards for learning Spanish; any words I am confident about, I set aside to give Pilar. At around six, our appointed time, I knock on Pilar’s trailer door. Nobody answers, and I am surprised at how disappointed I am. I leave her a note saying I stopped by.

A while later there is a knock at the door, a mom and her kids looking for Maria’s mother, Andrea. She’s surprised to hear they’re gone, but walks off unfazed; she’ll come back later.

The same story repeats itself later as dusk falls, and just as darkness overtakes the twilight, there’s a knock at the door again. I open it to find a hunched, older woman with a plastic grocery bag. She’s looking for Andrea, too.

No, I’m sorry, she went to Oaxaca to see her mother. Can I help you?

She’s gone? Julio, too?

Yes, I’m sorry. I’m a friend of Maria.

She doesn’t let me finish. I brought these green beans for them. Do you want them?

I look at the bag, bulging with several pounds of string beans.

You don’t want them?

She shakes her head. I picked them today in the fields, we took some. I can’t eat all of it.

Me neither, I say. She looks appalled, so I backtrack: But I can take a little.

Do you have a bag? she asks. She’s very organized, this woman.

I do—inside—so I pull out a few handfuls of beans and drop them into a bag. Thank you so much!

No, take more! she says, forcibly adding beans to my bag. I manage to stop her around the halfway mark. I have no idea what I’ll do with all these beans. I don’t even like green beans.

That’s enough for me, I say cheerfully, rapidly twisting the bag to prevent any unwanted additions. Thank you so much. How do you know Andrea and Julio?

Andrea is my cousin. When are Andrea and Julio back?

Maria told me two weeks.

She nods, makes a little huffing noise that sounds like approval, and turns to leave.

Thank you for the beans, I say, holding my bag aloft. She doesn’t say anything, just waves her hand in the air as she closes the gate and walks into the dark.

Pilar doesn’t show up, and I go to bed worrying that I’ve somehow missed my chance, but in the morning Sergio knocks on my door. Across the yard I can see Pilar watching from her doorstep as her son explains, in fluent English, that there is work tomorrow. Since we couldn’t study last night, maybe I can come over tonight for an English lesson, and Pilar can talk to me about work?

I barely notice the quid pro quo at work, charmed by Pilar’s mix of chutzpah and bashfulness. Of course, I say, relieved that my day of anxious unemployment has been transformed into a day off. By the time I go to bed that night, I’ll have handed over a stack of vocabulary cards to Pilar, borrowed cotton gloves, and gotten my marching orders. I’m to report to the corner of Panama and Tejon at 5:30 a.m. sharp. I should bring my own lunch. Pilar will bring me the tools I’ll need.

Cars are already creeping through the trailer park when I rise at 4:45 the next morning, just in time to hear Pilar’s truck pull out of the driveway next door. Even at this early hour, the sky is fading from black to deep blue in the east, the Sierra Nevadas a dark silhouette against it. I throw the burritos I made last night into my cooler, along with two water bottles I’d frozen and a big water jug.

I am out the door at 5:15 and head east toward the dawn, careening over shoulderless two-lane roads crowded with farmworkers.6 Nobody is at the appointed intersection, so I drive past it to a line of trucks and realize they’re for the workers already in the field to my right: Bulging burlap sacks line up like soldiers, and white orbs litter the ground, nearly glowing in the early light. Onions. I turn around and go back to Panama and Tejon, and this time Pilar is waiting for me. She signals for me to follow her and we drive farther east, pull off the road, and wait. For twenty minutes I sit there, listening to the rapid-fire Spanish of Radio Campesina, a station run by the United Farmworkers, and watching Pilar and the woman she’s carpooling with fix their work clothes. The woman riding with Pilar takes off her ball cap, folds a bandana in half diagonally and ties it over her nose and mouth. Then she folds a second bandana in half, into a rectangle, ties two corners together, and settles the narrow circle over the crown of her head. Then she puts her hat over all of it.

The sun is starting to rim the top of the mountains in gold, the sky above them turning to a silvery blue. More cars pull up behind me. A short, ponytailed man with a Yankees cap and a Detroit Lions sweatshirt walks past my car to Pilar’s. They talk for a while, and he looks at me questioningly—irrationally, I slink lower in my seat—then returns to his own car. Finally, around six, a big pickup pulling a trailer filled with hand trucks pulls up. This is the signal. Brake lights burn red, headlights switch on, and our caravan heads east, past oranges and grapes and almonds, down Panama Road, heading toward the mountains. Just as the sun crests the hills, turning the tops of the vines from deep green to chartreuse, we hang a right onto a road of washboard ridges. We turn down a lane, driving into the grape field, and when the truck finally stops, we all get out.

There is a flurry of activity. Men help the truck driver pull the hand trucks off the trailer, along with stacks of shallow plastic bins. Pilar helps me tie my bandanas properly; the extra layer of fabric makes my hat tight against my skull. Then she affixes her own: a pink gingham affair in which the hair cover and face mask neatly Velcro together, giving the appearance of a cheerful burka from the neck up. She wears a broad-brimmed straw hat, and I worry that my ball cap will be insufficient. Then she sets up a folding shade tent and a single Igloo cooler. And then: Nothing. We loiter. We are waiting for the containers to pack the grapes into, and until they arrive there’s no sense in picking.

We wait nearly two hours, until eight o’clock, which gives everyone ample time to observe my presence. I had hoped that my bandanas would help me blend in; save for the sliver of face around my eyes, every inch of skin is covered, and my hair and eyes ar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Description

- Author Bio

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Before you Read This Book

- Introduction: Eating in America

- Part I: Farming

- Part II: Selling

- Part III: Cooking

- Conclusion: A New American way of Eating

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Cheap Food?

- About the Author

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Footnotes