![]() PART THREE

PART THREE

Simplifying Complex Negotiations![]()

Are You an Expert?

Many of you probably have lots of negotiation experience. Does having a lot of experience make you an expert? If not, what does true expertise require? In this chapter, we answer this question by examining the distinction between experience and expertise in negotiation. We also consider how you can best combine your experience with our framework for thinking rationally to improve the overall effectiveness of your negotiating skills.

Expertise, to many people, means the ability to get good results. This definition really doesn’t explain the true nature of expertise. Many people are experts, yet they don’t always get good outcomes. How can this be explained?

Focusing only on results ignores a critical factor in an expert’s ability to produce good outcomes—the role of uncertainty. While you’d like to be able to rely on experts to make decisions that always result in good outcomes, experts, like everyone, often make their choices in the face of uncertainty. Thus, experts can make decisions that have poor results, and novices can make decisions that have great results.

Think about how you might decide what wine to buy. In choosing among the different kinds, you may rely on experts’ reviews. The recent reviews of Chateau Potelle’s 1988 chardonnay illustrate how easily it is for acknowledged experts to disagree. The chardonnay got great reviews from The Wine Spectator, which reported, “Smooth, concentrated and well-behaved … deep fruit flavors and a sense of intensity … delicious to drink now but it could be cellared until 1992.” It was given a rating of 88 out of 100 points. But the review in The Wine Advocate read, “Here is another bitterly acidic, austere, lean, thin wine … no pleasure, no character and no soul.” The same wine got 67 out of 100 points. Both of these experts can’t be right. So, if you were looking for a good white wine, would you consider Chateau Potelle’s 1988 chardonnay?1

While these two publications are marketed as offering expert opinions, the differences could just be chalked up to differences in the reviewers’ personal tastes. Experts also often disagree on what should be purely factual information, such as how to prepare the taxes for a family of four. Each March, Money magazine publishes the results of the following “test.”

During each of the last four years, fifty professional tax preparers were asked to complete a 1040 form for a hypothetical family of four. In 1988, no two preparers computed the same amount of tax due—their figures ranged from $7,202 to $11,881. In 1989, the preparers reported taxes due ranging from $12,539 to $35.831. In the 1990 test, the hypothetical family had an annual income of $132,000 and the taxes due ranged from $9,806 to $21,216. In the 1991 test, only one preparer reported to Money the correct tax of $16,786 on an annual income of just under $200,000. The other 48 returns (one preparer did not submit a return) reported taxes due ranging from $6,807 to $73,247 and, as in the past four years, there were almost as many different answers as there were tax preparers. In addition, each year Money found no connection between the fees the preparers charged their clients and performance. In 1991, the best performing preparer, and the two worst, all charged around the same, average fee of $86 per hour.2

If experts cannot agree, then what about novices? You can probably think of people you know who’ve gotten great deals, not because of any specific expertise, but just because they happened to be in the right place at the right time. Consider the deal a twelve-year-old baseball card collector got.

Twelve-year-old Brian Wrzensinski bought a Nolan Ryan “rookie” card for $12 from a baseball-card store in Addison, Illinois. It turns out that the card is worth somewhere between $800 and $1200.3 Brian bought the card a few days after the store had opened for business. It was quite busy and the owner had asked a clerk from a nearby jewelry store to help out. The substitute clerk didn’t know anything about baseball or baseball cards. When Brian asked if the card cost $12, the clerk looked at the $1200 price and interpreted it as $12—the price she charged Brian. While Brian didn’t know exactly how much the card was worth, he did say that he had seen similar cards for $150 and up. “I knew the card was worth more than $12,” he said. “I just offered $12 for it and the lady sold it to me. People go into card shops and try to bargain all the time.”4

“Even a blind hog picks up an acorn every now and again.”

Great outcomes can happen—a blind hog can occasionally find acorns or a twelve-year-old baseball card collector can buy an extremely rare card for $12—but not because of true expertise. Such lucky outcomes cannot be predicted or relied on.

Thus, experts err and novices succeed—sometimes. Complete success in negotiation is not a reasonable goal. Your goal should be to develop the ability to make better negotiated decisions most of the time. The true test of an expert is: over the course of multiple negotiations, are they better able to get good results?

EXPERIENCE VERSUS EXPERTISE

Luck aside, a manager can get high-quality negotiation outcomes in two ways: (1) he or she may learn an effective pattern of behavior for a particular situation, without necessarily being able to generalize this knowledge to related situations, or (2) negotiate rationally by selecting strategies that are appropriate to the goals, opponents, and other factors that are unique to the situation. While it can be hard to distinguish these two processes in a particular negotiation, the differences become obvious when the situation changes. To get high-quality results across situations and over time, and thus move closer to expertise, you must combine your experience with the rational negotiation prescriptions we’ve defined.

Experience is very useful. It helps you understand which factors are important in a particular negotiation. Unfortunately, experience alone doesn’t guarantee good outcomes because it’s typically limited to the situations in which it was developed. While you may be the top sales person in your organization because of your consummate skill at closing negotiations, this doesn’t mean you can negotiate with your spouse successfully. The strategies you use at work won’t be as successful in this other, very different form of negotiation.

Robyn Dawes, a psychologist, highlights the drawbacks of learning only from experience.5 He notes that Benjamin Franklin’s famous quote “experience is a dear teacher” is often misinterpreted to mean “experience is the best teacher.” Dawes asserts what Franklin really meant was “experience is an expensive teacher,” because Franklin goes on to observe “yet fools will learn in no other [school].” Dawes writes,

Learning from an experience of failure … is indeed “dear,” and it can even be fatal…. Moreover, experiences of success may have negative as well as positive results when people mindlessly learn from them … people who are extraordinarily successful—or lucky—in general may conclude from their “experience” that they are invulnerable and consequently court disaster by failing to monitor their behavior and its implications.

Consider the recent history of labor/management relations in the United States. In the 1960s, both sides had some very experienced negotiators. When the United States became less economically competitive, labor and management continued to use old negotiation strategies in this new, more competitive environment. This led to a disastrous period of layoffs for organized labor and declines in U.S. manufacturing productivity. These negotiators had considerable experience, but they lacked the necessary expertise to adapt their strategies to the new global negotiating environment. While there clearly were other factors that led to the decline of American industry, the rigidity of labor-management relations certainly contributed.

Experience by itself, however, does not prepare you to adapt to new situations. Think about the simple task of getting a cab. You are in town for business and staying at a large hotel. How do you get a taxi? Probably, you just step outside, tell the doorman where you wish to go, and he’ll hail a cab for you. No big deal.

Now suppose you weren’t in New York or some other major U.S. city, but in Bangkok, Thailand, staying at the prestigious Oriental Hotel. If you needed a cab, the doorman at the Oriental would hail one for you and tell the driver where you wished to go. The taxi would cost about what you would expect. However, if you had walked down the street about twenty feet and gotten your own cab, the price of the same ride would be about 75 percent lower. You would never know about this price discrimination if you simply followed your experience-based model of getting a taxi because, in the U.S., walking the extra twenty feet wouldn’t save you money.

What you learn from experience is obviously limited by the experiences you’ve had. Thus, in negotiation, it’s also true that your ability to adapt what you’ve experienced to other situations is also limited.

LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE—WHY IS IT SO DIFFICULT?

Learning from experience is common enough. You are often in new situations and you learn how to behave through a process of trial and error. You act in a certain way and then monitor the results to figure out what to do or not to do in the future. Economists argue that this experience and feedback process can, for example, protect experts from the “winner’s curse” problem we discussed in Chapter 7.

Given sufficient experience and feedback regarding the outcomes of their decisions … most bidders in “real world” settings would eventually learn to avoid the winner’s curse in any particular set of circumstances. The winner’s curse is a disequilibrium phenomenon that will correct itself given sufficient time and the right kind of information feedback.6

However, to learn from experience you need accurate and immediate feedback, and this is often not available. As Amos Tversky and Danny Kahneman suggest:

… (i) outcomes are commonly delayed and not easily attributable to a particular action; (ii) variability in the environment degrades the reliability of feedback … (iii) there is often no information about what the outcome would have been if another decision had been taken; and (iv) most important decisions are unique and therefore provide little opportunity for learning … any claim that a particular error will be eliminated by experience must be supported by demonstrating that the conditions for effective learning are satisfied.7

It’s often difficult for executives to determine what types of feedback they need to evaluate the accuracy of their decisions. Selecting one alternative or making one set of choices often precludes your knowing the outcomes of other alternatives or choices—except in situations such as horse races where, after a race, you know not only whether the horse you bet on won, but how all the other horses you could have bet on finished. It’s hard to learn much from a chosen course of action if you can’t compare your results to the unchosen, alternative outcomes.

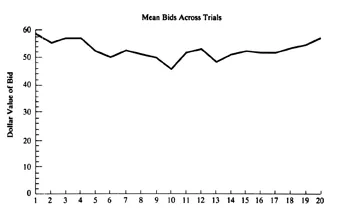

Even with feedback about your performance, it’s still difficult to learn from experience. In a recent study using the “Acquiring a Company” exercise we described earlier, we asked MBA students to respond to repeated presentations of the problem.8 We wanted to test their ability to incorporate the decisions of “others” (a computer played the role of the target firm) into their own decision making. The study used real money, and participants played twenty times. The results from each decision were reported to them immediately, and they could see how their asset balance changed (virtually always downward).

Remembering that $0 is the correct answer and that $50 to $75 is the typical answer, look at the mean bids across the twenty trials in figure 12.1. There is no obvious improvement—the average response hovers between $50 and $60. In fact, only five of sixty-nine participants ever discovered the correct solution (bidding $0) over the twenty trials. Thus, experience, even when coupled with feedback, failed to help participants improve their performance.

OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE

The major barrier to learning effectively from experience is, as we’ve suggested, that feedback about successful strategies is often unclear, delayed, or not given in a meaningful way. In addition, executives often have a psychological investment in the choices they make, reducing how open they are to feedback about their decisions. If a manager’s self-esteem depends on the outcome of the decision, this can make him or her see ambiguous feedback as more positive than it really is.9

Figure 12.1 “Acquiring a Company”—The Lack of Learning

Consider how difficult it is for your employees to hear and incorporate negative performance evaluations. Faculty often seem unable to hear (or let themselves acknowledge) negative feedback in their contract renewal or tenure review process. Most faculty who are denied tenure say they are surprised by the decision, regardless of the amount and type of negative feedback previously conveyed to them and documented in their personnel records.

Even if managers correctly understand relevant and meaningful feedback, that information still must be stored in their memory and then retrieved to be considered in later decisions. As we discussed earlier, memory storage and retrieval are influenced by many irrelevant factors. We are not contesting that people learn from experience—that is obviously true. We believe, however, that learning from experience does not usually produce the type of understanding that you need for true expertise. To be an expert at anything, you have to combine experience with rational thinking.

Thinking rationally about negotiation requires that you be able to discern a negotiation’s most important aspects, know why they are important, and know what strategies will be most effecti...