- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How To Outnegotiate Anyone

About this book

Come out ahead when dealing with the IRS, lawyers, ex-spouses, and other potentially unpleasant people.

How to Outnegotiate Anyone shows:

How to Outnegotiate Anyone shows:

- Why you should never disclose your deadline

- How to get the other side engaged and into a positive mindset

- When to deadlock (and when not to)

- How to tell the real final offer from the not-so-final offer

- And much more!

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How To Outnegotiate Anyone by Leo Reilly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Desarrollo personal & Negocios en general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Four

Offers And Counter-offers

Recently, at a seminar I was giving in Seattle, Washington, a real estate broker told me about a sale that took her less than 15 minutes to close. A newly married couple walked through a home that had just been put on the market. The market was very slow and it was a safe bet that the sellers would be very negotiable when it came to discussing price and terms. Within five minutes of entering the home, the couple asked the broker what the asking price for the house was. The broker responded by saying that the sellers were asking for $185,000. She was just about to add that she thought the sellers would be willing to come down from that price when the buyers cut her off: “Wow!,” they replied, “That's a lot less than we expected to pay for a house like this!” Needless to say, the seller underwent an immediate change in attitude. Instead of offering any significant concessions in price, the seller only made very modest concessions in price and refused to negotiate further. The deal closed on essentially the seller's terms.

The Opening Offer: Blow It And You're Dead

The very worst mistake any negotiator can make is blowing the opening offer. It is difficult, if not impossible, to recover from a blown opening offer. The reason is that the opening offer tends to set the other side's expectations as to what will happen during the balance of the negotiation session. If the other side's expectations are set unnecessarily high, you will have to prepare for them to be seriously disappointed when reality presents itself. If the opening offer sets the others side's expectations unnecessarily low, deadlock at the outset of negotiations can occur or, at the very least, tensions can arise and harden their position later on. Finally, as with the young couple who were buying their first home, a blown opening offer can lock us into a bad position early and make it difficult for us to escape from that position.

Use your brain before you open your mouth

The greatest single mistake you can make at the beginning stages of negotiations is simply not thinking carefully about your opening offer before you open your mouth. Resist the temptation to “get down to brass tacks” too early. Try to gather some information from the other side before you define your position. Ask yourself the following questions:

- What is it that the other side is trying to accomplish by negotiating?

- What is their perception of value?

- Do they appear to be flexible or inflexible?

- What do I need to know about the other side's position or perceptions before I begin to negotiate?

Remember, your opening offer has a direct impact on how negotiations proceed, whether you are able to keep the other side engaged in the process, and what their attitudes are toward negotiations as well as toward you. In short, opening offers are the first indication the other side receives from you as to how negotiations are going to proceed. Be patient and move carefully.

Wrong-Way Boulware's Fatal Mistake

Two years ago, I was teaching a seminar to members of the Army Corps of Engineers. At the end of a two-day class, one of the attendees, who had said nothing during the entire presentation, finally spoke up. “This information is fine,” he said, “but frankly, I don't think that it will do me any good.” I suppose that I was more than a little surprised, and even hurt, to hear that my entire course on negotiating had failed to impress him. “Why?” I asked. He explained that during his free time he invested in real estate. He would check out a neighborhood he was interested in and determine what the average market value of the homes were. Then he would pick a home he was interested in purchasing and approach the owner with an offer. He would tell the owner that he had seen all of the other homes for sale in the neighborhood and that he was willing to make a reasonable offer that was consistent with the comparables. He would also tell the seller that this offer, because it was fair, was not negotiable. Most of the time he was turned down. Occasionally, however, the owner would take the offer. The goal behind this strategy was, to use his own words, “not to have to waste all of that time negotiating.”

The first and final offer is popular with people who hate to negotiate. They usually make some valuation of the product or service in question, and then make an offer that is “fair,” consistent with this valuation. There is even a name for this strategy; it's called Boulwarism.

Lemuel Boulware was General Electric's senior vice-president in charge of the company's industrial relations for much of the 1950s. He formulated a negotiating strategy that was supposed to bring an end to G.E.'s troubled history of labor/management contract negotiations. Instead, his strategy made the situation worse.

Mr. Boulware had his accountants, financial advisors, labor negotiators, and other specialists put together a contract proposal that was “fair” to both labor and management. He then advised the labor union negotiators that this offer was the best he could do. In essence, he told them to take it or leave it. Mr. Boulware deadlocked, and his negotiating strategy led to a deterioration in General Electric's labor relations.

In retrospect, the reason is painfully clear. Boulwer-ism, in effect, forces one party to make all the concessions. If the labor union negotiators would have accepted the offer, they would have lost face and even looked inept in front of their members. In addition, even if Mr. Boulware's offer was reasonable, he would still end up looking unreasonable since he was insisting that the labor union make all the concessions if deadlock was to be avoided. As a result of Boulware's well intentioned but misplaced strategy, it is now presumed under federal labor law that a negotiator who opens with an offer and then refuses to make any concessions is “bargaining in bad faith.”10

Remember, in negotiations the process is as important as the result itself. If the negotiation process is mishandled, you can end up with a situation where you have made a generous proposal to the other side only to find out they hate you for it. The fact is, people expect to negotiate, and they expect concessions to be roughly equivalent for each side. If they feel the negotiation process was unfair or especially one-sided, you can end up with a situation where they will not accept a generous offer from you, even though they may have been happy to accept it under other circumstances.

To get back to my friend who liked to invest in real estate: How did he know that he couldn't have done even better? Let's suppose he didn't care about making a better investment and his only intention was to save time by bypassing the time consuming and annoying negotiation process. The likelihood is that he was spending more time, not less, trying to get a deal closed. I am willing to bet a dollar to a dime that he spent more time walking away from deals that might have been than the average buyer actually spends negotiating a deal to close.

Four Opening Gambits

Inasmuch as your opening offer has the effect of setting the other side's expectations, a well made opening offer is crucial in order to “anchor” the other side to the result you would like them to accept. Let's go through four different opening gambits in order to see how you can set, or anchor, the other side's expectations and adjust to their pre-existing expectations.

Let us assume you are interested in purchasing a home that has an asking price of $160,000. Let's further assume that $150,000 is the target price that you would like to purchase the home for. What should your opening offer be?

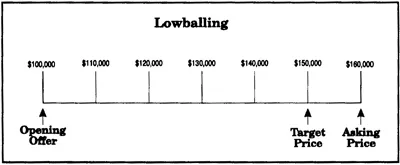

Scenario 1: “Lowballing”

Even though the asking price for the home is $160,000, let's assume in this scenario that your opening offer is very low, perhaps $100,000. The theory behind this type of opening is that it puts pressure on the other side throughout the entire negotiating session. Because you have lowballed your opening offer, you can make larger concessions than the other side, while complaining about the “small” concessions they are making. This puts them on the defensive and allows you to still come out with the better end of the deal.

Unfortunately, people who lowball the other side fail to take one crucial fact into consideration: the other side's initial reaction may be hostile. If the seller perceives your opening offer to be unacceptably low — and they usually do — their reaction will most likely be to harden their negotiating position and either get upset and refuse to negotiate, or counter with a trivial concession, such as $159,500, and then dig in.

The result is a harder seller for you to deal with and a greater likelihood of deadlock. The important thing to remember is that it does not matter if your opening offer actually is unreasonable, it only matters that the other side perceives it to be an unreasonable starting point for negotiations. When negotiating, the other side's perception of reality tends to be as important as reality itself.

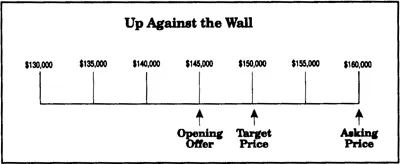

Scenario 2: Negotiating Against Your Target

In this second scenario, imagine you decide to open with an offer of $145,000 even though your goal is to purchase the home for $150,000 and the asking price is $160,000. Because you are negotiating closer to your $150,000 target than the other side is, the seller will have to make the greater number of concessions if the parties are to close at $150,000. Most likely, the other side will feel they are making more concessions than you are and that you are getting the better part of the bargain. You will tend to look stubborn or obstinate, and they may feel they are being pushed around or caused to lose face. As a result, there is a greater likelihood they will deadlock rather than close at the price of $150,000. Even if they do close at this price, there may be some effort on their part to even the score later, perhaps by refusing to act cooperatively in escrow when the transaction is actually being put together.

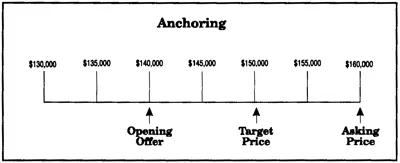

Scenario 3: “Anchoring” or “Telegraphing Your Punch”

Because the seller has an asking price of $160,000, you decide to open with an offer of $140,000 to “telegraph your punch” to the other side that you are looking to close at $150,000. This approach has a greater likelihood of success. In this scenario, the buyer can match almost any concession the seller makes with an equal concession of his own, and still arrive at an outcome of $150,000. If the seller counters with an offer of $157,000 the buyer then makes a counter of $143,000. At every stage of negotiations, the seller is reminded that an outcome of $150,000 is more and more likely to occur. The deal is “anchored.”

As an approach to bargaining, anchoring has two distinct advantages. First, it creates a sense that both parties are making equal concessions. This creates the impression that the process is being handled fairly and that nobody is getting the better part of the deal. As a result, the likelihood of one party retaliating against the other by hardening their position, or by retaliating later, is diminished. Second, it sets the other side's expectations early on in the negotiating process so they become acclimated to an outcome of $150,000. This actually makes it easier to accomplish a deal at this price.

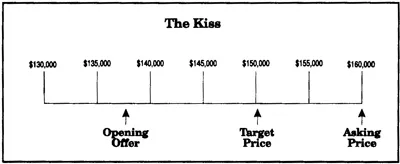

Scenario 4: “The Kiss”

This approach is similar to “anchoring,” with a minor modification. Instead of anchoring by an exact amount, $140,000, the buyer makes a slightly lower offer, say $137,500. The result is that the center of gravity between the parties is no longer $150,000, but $148,750. Now the buyer can close at $150,000 while still giving the seller $1,250 (a “kiss") in additional concessions over what the seller surrendered. I find this approach to be useful in highly contentious situations where the other side's ego is engaged and they are worried about “winning” and “losing".

The Cost of Opening First

A friend of mine, who grew up on a farm in Minnesota, once told me a story about a farmer who sold a horse to a city slicker for three times what it was worth. When he was asked how he got so much money for the rather mediocre nag, he replied: “Son, it's not what it's worth. It's what they think it's worth.” Economists frequently express this same truth with the saying: “A good or service is only worth what a buyer is ready, willing, and able to pay for it.”

One of the more common myths about the negotiating process is that there is something called objective value. In fact, objective value is an oxymoron, a self-contradicting phrase. Value is by definition subjective, not objective. What has worth to one person may have no value whatsoever to another. Imagine you are a collector of fine books and you find the last book in a series you are collecting. With this volume added to your collection, the series as a whole becomes very valuable, because your collection is complete. Without it, your collection is not worth nearly as much. To the bookstore owner, however, the individual value of the book may not be great at all. She only has this one book, not the rest of the series. Her valuation of the book's worth may be based on nothing more than what she paid for it with a mark-up for profit. In this transaction, the parties' relative opinions about the books value are defined by their respective needs. Needless to say, if one of the parties to this transaction knows more about the other side's opinion of the value, that person will usually do better when it comes to negotiating price.

In negotiating, the most important information you can get from the other side is their perception of value. Do not be seduced into thinking that value is static or objective. Rather than exclusively focusing on some objective assessment of what the item in question is worth, the best negotiators are also interested in the other side's perceptions. Opening first is opening blind.

The most important indicator to the other side's perception of value is their opening offer. As such, the party that makes the opening offer is usually at a disadvantage for the following reasons:

- They have communicated information about their perception of value to the other side.

- The opportunity to obtain the other side's opening offer, uninfluenced by our own, is lost.

- If you open first, the parameters of your negotiating position are automatically defined, and limited, before the other side moves.

Who usually makes the opening offer?

In general, the party that makes the opening offer is usually the party that lacks patience. Of course, there are exceptions to this rule. For example, tradition will often determine who must define their position first. If you are a car dealer, you generally have to have a sticker price in the window of every car you hope to sell. This sticker price is the first opening offer during negotiations. It defines the parameters of the seller's negotiating position, and it gives the buyer some information of the seller's perception of value. Similarly, if you are attempting to negotiate a dispute with someone, and you are the complaining party, you have an obligation to tell the other side what it is you want.

For the most part, however, the party that makes the opening offer is simply the one that lacks patience. The answer, therefore, is obvious. If there is no responsibility to make the opening offer, relax. Take your time. Try and gather information about the other side's perception of value before you move. Ask them what it is they want. The beautiful thing about most negotiators is that they cannot wait to express an opinion. Let them. And use this information to define what your counter-offer will be.

Remember, opening first is opening blind.

One Time to Open First

There is a theory that exists in certain sectors of the retail industry that argues th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- The Power of Patience

- The Power of a Positive Relationship

- Deadlocking

- Offers And Counter-offers

- Status and The Negotiator

- Buyer vs. Seller

- The Power of Information

- On Intimidation

- And Finally …

- Dealing with Buyer's Remorse

- Dealing with Seller's Remorse

- Team Negotiating

- Negotiating by Telephone

- Bibliography