- 880 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

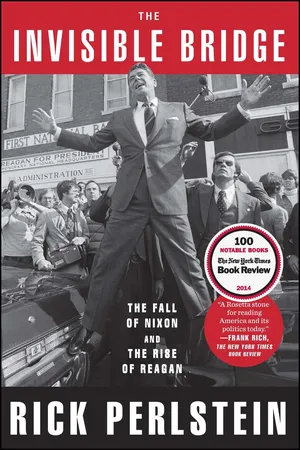

The New York Times bestselling portrait of America on the verge of a nervous breakdown in the tumultuous political and economic times of the 1970s is "a Rosetta stone for reading America and its politics today" (Frank Rich, The New York Times Book Review).

In January of 1973 Richard Nixon announced the end of the Vietnam War and prepared for a triumphant second term—until televised Watergate hearings revealed his White House as little better than a mafia den. The next president declared upon Nixon’s resignation “our long national nightmare is over”—but then congressional investigators exposed the CIA for assassinating foreign leaders. The collapse of the South Vietnamese government rendered moot the sacrifice of some 58,000 American lives. The economy was in tatters. And as Americans began thinking about their nation in a new way—as one more nation among nations, no more providential than any other—the pundits declared that from now on successful politicians would be the ones who honored this chastened new national mood.

Ronald Reagan never got the message. Which was why, when he announced his intention to challenge President Ford for the 1976 Republican nomination, those same pundits dismissed him—until, amazingly, it started to look like he just might win. He was inventing the new conservative political culture we know now, in which a vision of patriotism rooted in a sense of American limits was derailed in America’s Bicentennial year by the rise of the smiling politician from Hollywood. Against a backdrop of melodramas from the Arab oil embargo to Patty Hearst to the near-bankruptcy of America’s greatest city, The Invisible Bridge asks the question: what does it mean to believe in America? To wave a flag—or to reject the glibness of the flag wavers?

In January of 1973 Richard Nixon announced the end of the Vietnam War and prepared for a triumphant second term—until televised Watergate hearings revealed his White House as little better than a mafia den. The next president declared upon Nixon’s resignation “our long national nightmare is over”—but then congressional investigators exposed the CIA for assassinating foreign leaders. The collapse of the South Vietnamese government rendered moot the sacrifice of some 58,000 American lives. The economy was in tatters. And as Americans began thinking about their nation in a new way—as one more nation among nations, no more providential than any other—the pundits declared that from now on successful politicians would be the ones who honored this chastened new national mood.

Ronald Reagan never got the message. Which was why, when he announced his intention to challenge President Ford for the 1976 Republican nomination, those same pundits dismissed him—until, amazingly, it started to look like he just might win. He was inventing the new conservative political culture we know now, in which a vision of patriotism rooted in a sense of American limits was derailed in America’s Bicentennial year by the rise of the smiling politician from Hollywood. Against a backdrop of melodramas from the Arab oil embargo to Patty Hearst to the near-bankruptcy of America’s greatest city, The Invisible Bridge asks the question: what does it mean to believe in America? To wave a flag—or to reject the glibness of the flag wavers?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Invisible Bridge by Rick Perlstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

“Small and Suspicious Circles”

ONCE UPON A TIME WE had a Civil War. More than six hundred thousand Americans were slaughtered or wounded. Soon afterward, the two sides began carrying out sentimental rituals of reconciliation. Confederate soldiers paraded through the streets of Boston to the cheers of welcoming Yankee throngs, and John Quincy Adams II, orating from the podium, said, “You are come so that once more we may pledge ourselves to a new union, not a union merely of law, or simply of the lips: not . . . of the sword, but gentlemen, the only true union, the union of hearts.” Dissenters from the new postbellum comity—like the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who argued that the new system of agricultural labor taking root in the South and enforced by Ku Klux Klan terror hardly differed from slavery—were shouted down. “Does he really imagine,” the New York Times indignantly asked, “that outside of small and suspicious circles any real interest attaches to the old forms of the Southern question?”

America the Innocent, always searching for totems of a unity it can never quite achieve—even, or especially, when its crises of disunity are most pressing: it is one of the structuring stories of our nation. The “return to normalcy” enjoined by Warren Harding after the Great War; the cult of suburban home and hearth after World War II; the union of hearts declaimed by Adams on Boston’s Bunker Hill parade ground after the War Between the States.

And in 1973, after ten or so years of war in Vietnam, America tried to do it again.

On January 23, four days into his second term, which he had won with the most commanding landslide in U.S. history, President Richard Nixon went on TV to announce, “We have concluded an agreement to end the war and bring peace with honor in Vietnam and South Asia.” The Vietnam War was over—“peace with honor,” in the phrase the president repeated six more times.

But “it wasn’t like 1945, when the end of the war brought a million people downtown to cheer,” Mike Royko, the Chicago Daily News’ regular-guy columnist, wrote. “Now the president comes on TV, reads his speech, and without a sound the country sets the clock and goes to bed.” He was grateful for it. “There is nothing to cheer about this time. Except that it is over. . . . Mr. Nixon’s efforts to inject glory into our involvement were hollow. All he had to say was that it is finally over.”

Royko continued, “It is hard to see the honor. . . . Why kid ourselves? They didn’t die for anyone’s freedom. They died because we made a mistake. And we can’t justify it with slogans and phrases from other times.

“It was a war that made the sixties the most terrible decade our history. . . . If we insist on looking for something of value in this war then maybe it is this:

“Maybe we finally have the painful knowledge that we can never again believe everything our leaders tell us.”

Others, though, longed for the old patriotic rituals of reconciliation. And their vehicle became the prisoners of war held in Hanoi by our Communist enemies. “The returning POWs,” Secretary of Defense Elliot Richardson told the president, “have dramatically launched what DOD is trying to do to restore the military to its proper position.” The president, pleased, agreed: “We now have an invaluable opportunity to revise the history of this war.”

It began twenty days after the president’s speech, at the airport in Hanoi. What the Pentagon dubbed “Operation Homecoming” turned the network news into a nightly patriotic spectacle. Battered camouflage buses conveyed the first sixty men to the planes that would take them to Clark Air Base in the Philippines; a Navy captain named Galand Kramer unfurled a homemade sign out the window, scrawled on a scrap of cloth: GOD BLESS AMERICA & NIXON. The buses emptied; officers shouted out commands in loud American voices to free American men, who marched forth in smart formation, slowing to accommodate comrades on crutches. On the planes, and on TV, they kissed nurses, smoked too many American cigarettes, circulated news magazines with their wives and children on the cover, and drank a pasty white nutrient shake whose taste they didn’t mind, a newsman explained, because it was the first cold drink some of them had had in eight years. On one of the three planes they passed a wriggling puppy from lap to lap. “He was a Communist dog,” explained the Navy commander who smuggled him to freedom in his flight bag, “but not anymore!”

At Clark, the tarmac was thronged by kids in baseball and Boy Scout uniforms, women in lawn chairs with babes in arms, airmen with movie cameras, all jostling one another for a better view of a red carpet that had been borrowed at the last minute from Manila’s InterContinental Hotel because the one Clark used for the usual round of VIPs wasn’t sumptuous enough. In a crisp brocaded dress uniform with captain stripes newly affixed, Navy flier Jeremiah Denton, the first to descend, stood erect before the microphone and pronounced in a slowly swelling voice:

“We are honored to have the opportunity to serve our country—”

(A stately echo: “country–country—country . . .”)

“We are profoundly grateful to our Commander in Chief and our nation for this day.”

(“Day—day—day . . .”)

“God—”

(“God—God—God . . .”)

“Bless—”

(“Bless—bless—bless . . .”)

“America!”

(“America—America—America . . .”)

In days to come cameras lingered on cafeteria trays laden with strawberry pie, steak, corn on the cob, Cornish game hens, ice cream, and eggs. (“Beautiful!” sighed a man in a hospital gown on TV to a fry cook whipping up eggs.) When the men were in Hawaii for refueling on Valentine’s Day, the cameras luxuriated over the nurses who defied orders and broke through the security line to bestow leis on their heroes. Then the cameras followed the men to the base exchange, where a boom mike overheard Captain Kramer gingerly trying on a pair of bell-bottomed pants: “I must say, they’re a little different from what I would normally wear!”

The next stop was Travis Air Force Base in California, where for twelve long years the flag-draped coffins had come home. Now it was the setting for Times Square 1945 images: wives leaping into husbands’ arms; teenagers unabashedly knocking daddies off their feet; seven-year-olds bringing up the rear, sheepish, shuffling—they had never met their fathers before. From there the men shipped out to service hospitals around the country, especially prepared for their return with color TVs and bright yellow bedspreads to mask the metallic hospital tone; once more words like “God—God—God” and “duty—duty—duty” and “honor—honor—honor” and “country—country—country” echoed across airport tarmacs. The first men to touch ground had been given expedited discharge to comfort terminally ill relatives. Press accounts credited at least one mother with a miraculous recovery. Miracles, according to the press, were thick on the ground.

“The first thing she did when she raced to embrace her husband . . . was slip his wedding ring on his finger. The ring, she told reporters, had been sent to her, along with her husband’s wallet. . . .”

“ ‘By all rights he should have come out on a stretcher. But he refused and was determined he was going to come out walking.’ ”

“When Captain John Nasmyth Jr. landed after years of captivity, a dozen strangers rushed up to him and thrust into his hand metal bracelets bearing his name. The strangers had been wearing the bracelets for as long as two years or more, as amulets of their concern and their faith in his safe return.”

Those bracelets: invented by a right-wing Orange County, California, radio host named Bob Dornan, they became a pop culture phenomena in 1970 after being introduced at a “Salute to the Armed Forces” rally in Los Angeles hosted by Governor Ronald Reagan. By the summer of 1972, they were selling at the rate of some ten thousand per day. Wearers vowed never to remove them until the name stamped on the metal came home. Some, the New York Times reported, believed them to “possess medicinal powers”—and not just the children who displayed them two, ten, a dozen to an arm. A Wimbledon champ said one cured his tennis elbow. The pop singers Sonny and Cher wore them on their hit TV variety show. Lee Trevino insisted his bracelet saved his golf game. And now that they were no longer needed, there was talk of melting them down for a national monument on the Mall in Washington, D.C.

When Captain Nasmyth arrived in his hometown, he was led to a billboard that read HANOI FREE JOHN NASMYTH. He chopped it down with a ceremonial ax, his entire community gathered round as a fifty-three-piece band blared “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.” A black POW addressed a undergraduate classroom at a black university in Tennessee. The students examined him as if they had unearthed, a newspaper said, a “member of a nearly extinct sociological species: American Negro, circa 1966.” He told them, “We have the greatest country in the world.” That made front-page news, too.

One of the most quoted returning warriors was a colonel who noted all the signs reading “We Love You.” “In a deeper sense,” he said, “I think what people are saying is ‘We Love America.’ ” Another announced the greatest Vietnam miracle of all: that the POWs had won the Vietnam War. “I want you all to remember that we walked out of Hanoi as winners. We’re not coming home with our tails between our legs. We returned with honor.”

NBC broadcast from a high school in a tiny burg in Iowa—John Wayne’s hometown—where wood shop students fashioned a giant key to the city for a POW native son; then the anchorman threw to his correspondent in the Philippines, who filled five full minutes of airtime calling the names, ranks, service branch, and hometowns of twenty exuberant Americans as they bounded, limped, or, occasionally, were borne upon stretchers, down the red carpet, to their next stop, the base cafeteria. (“Scrambled eggs!” “How many?” “How many can you handle?”) The screen filled with a red-white-and-blue banner. NBC’s Jack Perkins signed off: “The prisoners’ coming back seems the one thing about Vietnam that has finally made all Americans finally, indisputably, feel good.”

Not all Americans. Columnist Pete Hamill, on Valentine’s Day in the liberal New York Post, pointed out that the vast majority of the prisoners were bomber pilots, and thus were “prisoners because they had committed unlawful acts”—killing civilians in an undeclared war. He compared waiting for the POWs to come home to his “waiting for a guy up at Sing Sing one time, who had done hard time for armed robbery.”

There was the New York Times, which in one of its first dispatches from the Philippines reported, “Few military people here felt the return of the prisoners marked the end of the fighting. ‘They’re sending out just as many as come back,’ said a young Air Force corporal who works at the airport. ‘They’re all going to Thailand, they’re just moving the boundaries of the war back.’ ”

Not even all POWs agreed they were heroes. When the first Marine to be repatriated arrived at Camp Pendleton, every jarhead and civilian employee on base stood at attention to receive him. After the burst of applause stopped, Edison Miller held up a clenched fist in the manner favored by left-wing revolutionaries, then turned his back to the crowd.

In fact nothing about the return of the POWs was indisputable; the defensiveness of the president’s rhetoric demonstrated that. At a meeting of the executive council of the AFL-CIO in Florida on February 19, Nixon spoke of the “way that our POWs could come off those planes with their heads high, knowing that they had not fought in vain.” The next day, before a joint session of the South Carolina legislature, he answered a Gold Star Mother who wrote to him questioning the meaning of her son’s sacrifice: “I say to the members of this assembly gathered here that James did not die in vain, that the men who went to Vietnam and have served there with honor did not serve in vain, and that our POWs, as they return, did not make the sacrifices they made in vain.”

With honor, not in vain: a whole lot of people must have been worrying otherwise. Or else it wouldn’t have been repeated so much.

“The nation begins again to feel itself whole,” proclaimed Newsweek. Time speculated how “these impressive men who had become symbols of America’s sacrifice in Indochina might help the country heal the lingering wounds of war.” However, some stubbornly refused to be healed. It would take more than a “Pentagon pin-up picture,” a Newsweek reader wrote, to make her forget “that these professional fighting men were trained in the calculated destruction of property and human life.” A Time reader spoke up for his fellow “ex-grunts,” who had received no welcoming parades: “Why were we sneaked back into our society? So our country could more easily forget the crimes we committed in its name?”

TURN ON THE TV, OPEN a newspaper or a dentist-office magazine, and a new journalistic genre was now impossible to avoid: features that affected to explain to these Rip van Winkles all they had missed while incommunicado in prison camps at a time when, as NBC’s gruff senior commentator David Brinkley put it, “a decade now is about equal to what a century used to be, because change is so fast.”

On February 22 the Today show devoted both its hours to the exercise. “Generally, they’ve been years of crisis,” the anchorman began.

A DEMAND EQUALITY sign:

“They walked in picket lines, they badgered congressmen, they formed pressure groups”—Who? The attractive blond newscaster (there weren’t any of those in 1965), whose name was Barbara Walters, was speaking of women, only ordinary women. “They strived for ‘lib,’ ” she continued—“as in liberation.”

A mob of long-haired young men:

“Protest, demonstrations, disorders, riots, even death flared” on elite college campuses, where students “didn’t trust anyone over thirty” and contested “the whole fabric of Western Judeo-Christian morality.”

Gene Shalit, Today’s bushy-haired entertainment critic, reported how “federal legislation brought the vote to two million more blacks,” and that “in 1964, when the first POWs were taken in Vietnam, most of us thought that was what was wanted. The phrase most often used was ‘equal opportunity.’ . . . Then came 1967 and a riot in Detroit. . . . There was Malcolm X, a failure in every way according to the ‘white’ code; he became a folk hero among blacks.”

Nineteen new nations, from Bangladesh to Botswana; a war in Israel won in six days—“but terrorism followed”: cue picture of a man in a ski mask on a balcony in Munich, at the 1972 Olympics.

Bonnie and Clyde, the hit movie from 1967, made the criminal life “look like fun and games” and changed Hollywood; The Godfather, from 1972, “the biggest moneymaker since 1965’s Sound of Music,” “at once glorified and sentimentalized the mafia.” Last Tango in Paris, in theaters now, featured “clear depictions of the most elemental sexual acts, and perhaps some aberrations as well, but what it shows most is that here in New York at five dollars a ticket the film is a sellout, and that ordinary respectable folks like you are all going to see it.”

Finally there came a familiar Hollywood image: a tall, handsome man in a Stetson. But the still was from Midnight Cowboy, and the camera pulled back to show that the titular cowboy was hugging a shrunken and disheveled Jewish man, and Barbara Walters explained it signified the new Hollywood trend “toward dealing openly with homosexuality.”

Assassinations and attempted assassinations: Malcolm X. Martin Luther King. Robert F. Kennedy. George Wallace.

Fashion: “Unisex—remember that word. . . .”

Some ninety minutes later, two chin-stroking penseurs were asked by the stern-voiced anchorman what was the most profound change the POWs faced. Answered the editor of Intellectual Digest: “For the first time Americans have had at least a partial loss in the fundamental belief in ourselves. We’ve always believed we were the new men, the new people, the new society. The ‘last best hope on earth,’ in Lincoln’s terms. For the first time, we’ve really begun to doubt it.”

THIS PRETENSE THAT SOME SIX hundred POWs newly returned to their families would want to waste two hours of their lives learning about the latest slang from Gene Shalit felt a little bit fantastic. But the ritual was not for them. It was for us—all those Americans doubting for the first time that America might just not be the last best hope on earth. “Having missed much of the destructiveness of these past few years,” one letter writer to the Washington Post exulted, they had “preserved a vision of the way America ought to be.” As if these men might somehow be able to mystically deliver us across the bridge of years—to the time before the storm. It was their gift to us.

On the CBS Evening News the same day as that Today show, a lovely bride was seen with a man in officer’s dress, a wedding march pealing forth from the organ. Walter Cronkite narrated:

“Dorothy said her husband’s return was like a resurrection, and that for her it was like a new life beginning. So she went out and bought an all-new white wedding gown. And Dorothy and Johnny Ray reaffirmed the marriage vow they first made four and a half years ago.”

(Cut to ten seconds on the long white train of her gown, then the cross above the altar; fifteen seconds of him slipping on the wedding ring.)

“It was a short, simple ceremony.”

(Kiss, organ, recessional.)

“Captain and Mrs. Johnny Ray will soon be home to their three children in Pauls Valley, Oklahoma. David Dick, CBS News at the post chapel, Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas.”

That was one sort of homecoming s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Preface

- Chapter One: “Small and Suspicious Circles”

- Chapter Two: Stories

- Chapter Three: Let Them Eat Brains

- Chapter Four: Executive Privilege

- Chapter Five: “A Whale of a Good Cheerleader”

- Chapter Six: Sam Ervin

- Chapter Seven: John Dean

- Chapter Eight: Nostalgia

- Chapter Nine: The Year Without Christmas Lights

- Chapter Ten: “That Thing Upstairs Isn’t My Daughter”

- Chapter Eleven: Hank Aaron

- Chapter Twelve: “Here Comes the Pitch!”

- Chapter Thirteen: Judging

- Chapter Fourteen: “There Used to Be a President Who Didn’t Lie”

- Chapter Fifteen: New Right?

- Chapter Sixteen: Watergate Babies

- Chapter Seventeen: Star

- Chapter Eighteen: Governing

- Chapter Nineteen: “Disease, Disease, Disease”

- Chapter Twenty: New Right

- Chapter Twenty-One: Weimar Summer

- Chapter Twenty-Two: The Nation’s Soul

- Chapter Twenty-Three: “Has the Gallup Poll Gone Bananas?”

- Chapter Twenty-Four: Negatives Are Positives

- Chapter Twenty-Five: “Not the Candidate of Kooks”

- Chapter Twenty-Six: Born Again

- Chapter Twenty-Seven: “Always Shuck the Tamale”

- Chapter Twenty-Eight: They Yearned to Believe

- Chapter Twenty-Nine: Bicentennial

- Chapter Thirty: “You’re in the Catbird Seat”

- Chapter Thirty-One: “Don’t Let Satan Have His Way—Stop the ERA”

- Chapter Thirty-Two: The End?

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Sources

- About Rick Perlstein

- Index

- Photo Credits

- Copyright