- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A “must-read” (Booklist) from Harvard Business School Professor and Codirector of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Center for Public Leadership: A guide to making better decisions, noticing important information in the world around you, and improving leadership skills.

Imagine your advantage in negotiations, decision-making, and leadership if you could teach yourself to see and evaluate information that others overlook. The Power of Noticing provides the blueprint for accomplishing precisely that. Max Bazerman, an expert in the field of applied behavioral psychology, draws on three decades of research and his experience instructing Harvard Business School MBAs and corporate executives to teach you how to notice and act on information that may not be immediately obvious.

Drawing on a wealth of real-world examples and using many of the same case studies and thought experiments designed in his executive MBA classes, Bazerman challenges you to explore your cognitive blind spots, identify any salient details you are programmed to miss, and then take steps to ensure it won’t happen again. His book provides a step-by-step guide to breaking bad habits and spotting the hidden details that will change your decision-making and leadership skills for the better, teaching you to pay attention to what didn’t happen, acknowledge self-interest, invent the third choice, and realize that what you see is not all there is.

While many bestselling business books have explained how susceptible to manipulation our irrational cognitive blind spots make us, Bazerman helps you avoid the habits that lead to poor decisions and ineffective leadership in the first place. With The Power of Noticing at your side, you can learn how to notice what others miss, make wiser decisions, and lead more successfully.

Imagine your advantage in negotiations, decision-making, and leadership if you could teach yourself to see and evaluate information that others overlook. The Power of Noticing provides the blueprint for accomplishing precisely that. Max Bazerman, an expert in the field of applied behavioral psychology, draws on three decades of research and his experience instructing Harvard Business School MBAs and corporate executives to teach you how to notice and act on information that may not be immediately obvious.

Drawing on a wealth of real-world examples and using many of the same case studies and thought experiments designed in his executive MBA classes, Bazerman challenges you to explore your cognitive blind spots, identify any salient details you are programmed to miss, and then take steps to ensure it won’t happen again. His book provides a step-by-step guide to breaking bad habits and spotting the hidden details that will change your decision-making and leadership skills for the better, teaching you to pay attention to what didn’t happen, acknowledge self-interest, invent the third choice, and realize that what you see is not all there is.

While many bestselling business books have explained how susceptible to manipulation our irrational cognitive blind spots make us, Bazerman helps you avoid the habits that lead to poor decisions and ineffective leadership in the first place. With The Power of Noticing at your side, you can learn how to notice what others miss, make wiser decisions, and lead more successfully.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Power of Noticing by Max Bazerman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Racing and Fixing Cars

Welcome to my executive decision-making class, or at least the closest that I can get to teaching my class within a book. I often teach through simulations, and one of my favorite simulations for executive students is a brilliant decision-making exercise written by Jack Brittain and Sim Sitkin that requires students to decide whether or not to race a car on a certain day given particular conditions. Before presenting you with the simulation materials, I want to make it clear to you, as I do to my other students, that this exercise is not really about racing or engines, topics that I know nothing about.

Here is a summary of the facts that my executive students read:1

1. A racing team was getting ready for its final race of the season after a very successful season. The team had finished in the top five in twelve of the fifteen races that it had completed.

2. The team’s car had suffered gasket failures in seven of the twenty-four races that it started (two races were not completed for other reasons), with each of the seven gasket failures creating various degrees of damage to the engine.

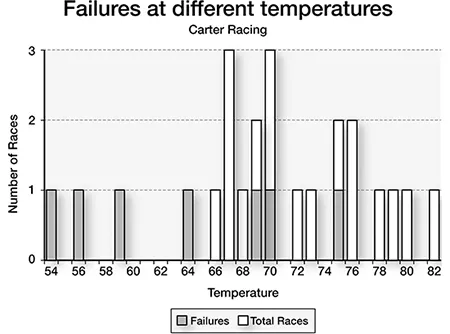

3. The engine mechanic thought that the gasket failures were related to ambient air temperature. The previous gasket failures were at 53, 56, 58, 64, 70, 70, and 75 degrees. The biggest failure occurred at the coldest temperature: 53 degrees. It was below freezing last night, and it was 40 degrees shortly before the race.

4. The chief mechanic disagreed with the engine mechanic’s view that the gasket failures were related to cold temperatures and pointed out that you don’t win races sitting in the pits.

5. The team had changed the seating position of the gaskets prior to the last two races, which may have solved the problem. However, the temperature for both of those races was in the 70s.

6. Today’s race is a high-profile event that will be covered on national television.

7. You estimate that if your team finishes the race in the top five, you will win a very big sponsorship that will put you in great financial shape for next year. However, if you have a gasket failure on national television, you will be out of business. Not racing or finishing out of the top five will not materially affect the team’s competitive position.

Do you race? It is time for you to make your decision.

The actual simulation materials provide more detail about the decision, but I have captured its essence. While the executives in my classes are reading these materials, I say to them three times, “If you want any additional information, please let me know.” Is there any other information that you need? For example, if you wanted to figure out whether temperature is related to gasket failure, what data would you need?

Most of my in-class executives do not ask for additional information, and most of them decide to race. They reason that the problem has only a 7/24 chance of occurring, and as the chief mechanic said, you don’t win races sitting in the pits. My students also consider the potential problem of low temperature but conclude that the data are inconclusive.

Tellingly, it is the rare executive who asks for critical information needed to test the temperature hypothesis. If you wanted to know if weather was related to engine failure, would you want to know the temperatures at which the engine failed, at which the engine didn’t fail, or both? Anyone armed with engineering skills, a basic knowledge of statistics, or simply a sound sense of logic can see that the answer is both. Yet despite being repeatedly told, “If you want any additional information, please let me know,” most executives never ask for the temperatures during the races when the engine did not fail.

For the few executives who do ask me about the temperatures during the races without gasket failures, I provide an additional information packet that reveals that races free of gasket failures occurred at 66, 68, 69, 72, 75, 79, 80, 82 degrees, plus two races at 70 and 76 degrees and three races at 67 degrees.

Does that change things? Now you might notice that your team failed to finish all four races that it started below 65 degrees, and that there is an extremely high correlation between low temperature and gasket failure. Perhaps a graph might help you see the pattern.

In fact, using data from all twenty-four races, a logistic regression puts the probability of failure in the current race at more than 99 percent. But if you don’t have the data on successful races, you have no basis for seeing this pattern. Most executives don’t have these data because they don’t ask for them, and they decide to race.

If you don’t know how to run a logistic regression, don’t worry. You do not need to. Back-of-envelope thinking works too. Perhaps the following summary will be convincing:

Gasket Failure Using all Data

Temperature | Races with Blown Gaskets | No. Races | Prob. |

< 65 | 4 | 4 | 100% |

65 - 70 | 2 | 10 | 20% |

71 - 80 | 1 | 9 | 11% |

> 80 | 0 | 1 | 0% |

In my class discussions, if it becomes clear that one executive correctly answered the problem because she asked for the data on the other seventeen races, others in the room object. The distribution of information, they protest, wasn’t fair. I point out that I repeated three times, “If you want any additional information, please let me know.” The executives respond that in other case studies they have worked on, the professor provided all the information they needed to solve the problem. They are right. But we are often presented with what seems like all the information we need to make a decision when, in fact, we should be asking for additional information.

What’s in front of you is rarely all there is. Developing the tendency to ask questions like “What do I wish I knew?” and “What additional information would help inform my decision?” can make all the difference. It can make you a far better decision maker, and it can even save lives.

Brittain and Sitkin wrote their simulation based on events that occurred on January 27, 1986, the evening before the launch of the space shuttle Challenger. Technically trained engineers and managers from Morton Thiokol and NASA discussed the question of whether it was safe to launch at a low temperature. Morton Thiokol was the subcontractor that built the shuttle’s engine for NASA. As you will not be surprised to hear, in seven of the shuttle program’s twenty-four prior launches, O-ring failures had occurred. Morton Thiokol engineers initially recommended to their superiors and NASA executives that the shuttle not be launched at low temperatures; they believed there was an association between low temperature and the magnitude of O-ring problems in the seven prior problem launches. NASA personnel reacted to the engineers’ recommendation with hostility and argued that Morton Thiokol had provided no evidence that should change their plans to launch.

Many of these experienced NASA engineers with rigorous training saw no clear observable pattern regarding the O-ring failures. Yet they clearly had the necessary background to know that in order to assess whether outdoor temperature was related to engine failure, they should examine temperatures when problems occurred and temperatures when they did not. But no one at Morton Thiokol presented and no one at NASA asked for the temperatures for the seventeen past launches in which no O-ring failure had occurred. As in the car-racing simulation, looking at all of the data shows a clear connection between temperature and O-ring failure and in fact predicts that the Challenger had a greater than 99 percent chance of failure. But, like so many of us, the engineers and managers limited themselves to the data in the room and never asked themselves what data would be needed to test the temperature hypothesis.

We often hear the phrase looking outside the box, but we rarely translate this into the message of asking whether the data before us are actually the right data to answer the question being asked. Asking for the right data puts you on the path to becoming a far better decision maker.

Postdisaster analyses documented that the Challenger explosion was caused by the failure of an O-ring on one of the solid rocket boosters to seal at low temperatures. The amazing failure of the Challenger’s engineers and managers to look outside the bounds of the data before them was an error committed by smart, well-intentioned people that caused seven astronauts to lose their lives and created the worst setback in NASA history. Unfortunately this type of error is all too common. We know from behavioral psychology that all of us routinely fall prey to the “what you see is all there is” error when making decisions. That is, we limit our analysis to easily available data rather than asking what data would best answer the question at hand. Even being steeped in the latest decision-making research isn’t a sufficient safeguard.

EMPATHIZING WITH NASA

NASA and Morton Thiokol made a truly terrible mistake. My first reaction is to hope that I would never make such an awful blunder. Some of my introspection provides comfort that I do not use just the information that is easily available w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Acknowledgments

- Preface: Noticing: A Personal Journey

- 1. Racing and Fixing Cars

- 2. Motivated Blindness

- 3. When Our Leaders Don’t Notice

- 4. Industrywide Blindness

- 5. What Do Magicians, Thieves, Advertisers, Politicians, and Negotiators Have in Common?

- 6. Missing the Obvious on a Slippery Slope

- 7. The Dog That Didn’t Bark

- 8. There’s Something Wrong with This Picture: Or, If It’s Too Good to Be True . . .

- 9. Noticing by Thinking Ahead

- 10. Failing to Notice Indirect Actions

- 11. Leadership to Avoid Predictable Surprises

- 12. Developing the Capacity to Notice

- About Max H. Bazerman

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright