![]()

ONE

Human Variety Before Race

Aesthetics, in both the broad sense of being about the non-rational aspects of the mind and in the narrower sense of being about beauty, had a vigorous and contentious life in Europe, especially in Britain, long before it was given definition by Baumgarten in 1751. In the first half of the century, and often later, matters of beauty and human variety were discussed primarily by philosophically minded generalists: ‘Virtuosi’ or Natural Philosophers in Britain, ‘Philosophes’ in France and ‘Gelehrten’ in the German lands. They were concerned with the deepest matters of human existence, unconfined by boundaries between academic disciplines. Hence pronouncements on both human variety and aesthetics were often made by the same people, not infrequently within the same discourse. The later part of the century, however, saw the triumph of academics in all fields to do with the history and interpretation of man; increasingly a distinction was made between amateur and professional.

Aesthetics and human variety as subjects of study followed ultimately from John Locke’s enquiries into the human mind. They are both aspects of ‘natural philosophy’, the belief that the human mind was as knowable as the human body through ‘unprejudiced Experience, and Observation’ and the exercise of logic.1 If aesthetics, even before the word was coined, became a way of enquiring into mankind’s non-rational perceptions or feelings, then anthropology, again avant la lettre, became the study of the way that human beings came to differ from each other according to their environment or their means of subsistence, on the almost universal understanding that mankind was originally a single people. Of course there was resistance to Locke in England, and especially in Germany, on theological grounds, and in France on grounds of Cartesian rationality. But empirical method, and the idea of man as an historical being, broadly prevailed in France and England. Aesthetics came to the fore as human behaviour came under philosophical scrutiny, and anthropology when theological objections to studying the history of man in secular terms could be overcome. If aesthetic response could be assumed to vary from person to person, and from one human group to another, then it made sense to enquire into the ways in which the aesthetic as well as other responses might be contingent on environment or other factors.

The primary division of the world inherited by early eighteenth-century Europe, the Four Continents of Europe, Africa, America and Asia, accounted for the whole of mankind within a single spatial frame. Everyone alive or who had ever lived could be given a physical and cultural locus in relation to the rest of humanity. The idea of ‘nation’ or people, on the other hand, had no set limits. Travellers could and did identify ever more peoples, and were able to observe differences from and similarities to others, sometimes across the already fluid boundaries of the traditional continents.

The Four Continents go back to the classical tripartite division of the world into Europe, Asia and Africa, to which America was added in the sixteenth century.2 The identification of Europe with Christendom was made at least as early as the fifteenth century, and by 1700 the word ‘Europe’ was virtually synonymous with, and the preferred term to, ‘Christendom’.3 Europe was identified in Montesquieu’s Lettres Persanes of 1721 as a place of frenetic activity and desire for enrichment, a puzzle to the visiting ‘Persians’, who were used to a static society and leisurely way of life.4 The idea of Europe as synonymous with Christendom was effectively, if incompletely, replaced in the eighteenth century by the claim of European moral and intellectual superiority over non-Europeans. In Le siècle de Louis XIV (1751) Voltaire argued that the strength of Europe in its political diversity was based ultimately on common principles, and added the idea of cultural superiority, the ‘republique litteraire’, the scientific and artistic community created by the internationalism within Europe of academies and universities.5 In 1756, in Essai sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations, Voltaire argued that Europe was now richer and more civilized than any other continent, even though civilization had originated in East, only being taken up in Europe at the end of the Middle Ages.6 Voltaire heralded a period from the 1750s to the 1770s when the identification of Europe with civilization became associated with progress, and the traditional line between civilization and barbarism was drawn between Europe and the rest of the world. For the philosophes, Europe could represent not only civilization but harmony in diversity through the balance of power; freedom as opposed to the despotism of Asia or the slavery of Africa; and energetic activity versus passivity.

The association of Europe with liberty had an ancient precedent in the distinction made between the Greeks and the despotic Persians, but, despite the growing assumption towards the end of the century and beyond that ancient Greece at its height represented Europe’s Golden Age, the Greeks had not necessarily thought of themselves as European at all. Aristotle saw the Greeks as a kind of buffer between Europe, represented by warlike Macedonia, and Asia and having the virtues of each; they were courageous like Europeans who lived in a cold climate, and skilled and intelligent as Asians, who lacked courage.7 The Greeks then were free themselves but capable of ruling others. From as early as circa 400 BC, Hippocrates, who was frequently invoked in the eighteenth century, had claimed that climate had been a factor in determining the character of inhabitants of each continent; the volatile climate of Europe made its inhabitants active and warlike while the hot climate of Asia created lassitude and despotism.

If Europe became increasingly stable as a concept in the eighteenth century, it remainded far from stable as a geographical entity. The only agreed border was the Mediterranean; beyond that the limits were vague. There was a sense also that the peoples beyond the eastern border of the Holy Roman Empire – the Circassians and others – were of exceptional contentment and beauty, as were those in parts of India; the presumption of their aesthetic superiority played a part in their incorporation into what was in the nineteenth century to become the ‘Aryan’ race. Furthermore ‘Europe’ had to co-exist with an increasing awareness, derived from exploration and trade, that peoples of different nations within each continent also had a specific character. Even so, there is a tendency in much of the anthropological writing of the period to think of Europe as made up of an infinite number of peoples, and Africa of only one or two.

What constituted a ‘nation’ could be maddeningly imprecise throughout the eighteenth century. Hume noted that ‘The vulgar are apt to carry all national characters to extremes’, but ‘Men of sense . . . allow, that each nation has a peculiar set of manners, and that some particular qualities are more frequently to be met with among one people than among their neighbours.’8 While it was well understood that England (usually encompassing the whole of Britain), France and Germany (in the last case in defiance of political reality) were nations, it is not unusual even in the second half of the eighteenth century for the whole of Africa to be referred to as a nation in the same terms.

The Continents had a vigorous presence in public art from the seventeenth century onwards; decorative schemes enthroned Europe as the source of wisdom and truth, or at least as the premier continent of the four. They could be represented as under the dominion of the Holy Ghost in Jesuit or missionary churches, or Apollo in more secular contexts; in Alpers and Baxandall’s words, ‘the Four Continents below a Heaven ruled by the Sun-God Apollo [was] . . . the ultimate cliché of Baroque iconography’.9 The respective iconography of the continents had been set down for painters by Cesare Ripa in his Iconologia,10 and his method of providing personified female figures with appropriate attributes remains almost universal not only in wall paintings, frescoes and frontispieces to books (illus. 2), but in popular representations well into the early nineteenth century. Europe’s mythical origins might be symbolized by Europa’s bull, and her other attributes might be a horse, a temple of religion, emblems of war and of the arts – architecture, painting, sculpture and music.

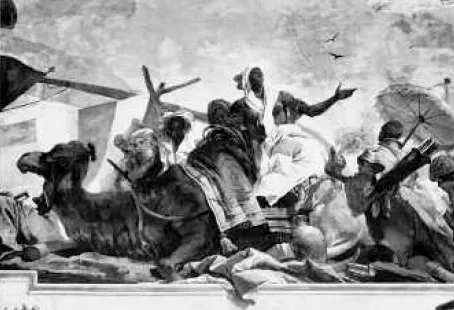

The developing iconography of Europe and of the other three Continents tended to follow conventional formulae,11 but Giambattista Tiepolo’s Africa in the Würzburg Residenz (illus. 3) reveals a rich sense of the geography and economy of Africa in relation to the other continents. Tiepolo used the whole side of the ceiling to create a dense image of trade and the carriage of goods from the interior of Africa to the Egyptian coast, and thence across the Mediterranean to Europe. The figure of Africa is set among a resting caravan train of Arab traders, and the ultimate destination of their goods is represented by two Europeans buying pearls from an oriental pearl-dealer. The interior and exterior of the geographical Africa are linked by the figure of the River Nile, which, from its mysterious origins, joins the dark heart of Africa and its Mediterranean periphery, where it faces Europe across the water.

2 Charles Grignion, The Four Continents, c. 1740, engraving after Hubert Gravelot.

3 Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, detail of Africa, c. 1751–3, fresco on the staircase ceiling, Residenz, Würzburg.

CONSTRUCTING THE SAVAGE

If, according to Locke, the mind contained no innate ideas, this could be taken to mean that all human beings were born in a state of mental equality, hence inequality must have been imposed by circumstances after birth. Locke did allow the mind an innate reasoning capacity that could vary from one person to another, but the idea of the mind as a tabula rasa taken literally would have meant that Europeans and non-Europeans were differentiated only by their differing experiences and education, not by inherent differences of ability. The denial of innate ideas could be used to argue against biological differences between peoples, and allow for the possibility that all human beings, whatever their heredity or circumstances, were capable of being educated. On the other hand, it could place just as absolute a gulf between those who were educated and those who were not. As Locke claimed at the beginning of Thoughts on Education, ‘of all the Men we meet with, Nine Parts of Ten are what they are, Good or Evil, useful or not, by their Education’.12 By education Locke meant, of course, the European kind, based on logic, observation and mental discipline.

Locke opened up the possibility of a historical and progressive view of man’s development based on natural law. Man can be seen to move from a natural free state, in which he lives in a nomadic society, or ‘America’, to one in which he owns property and lives in a community, graduating to a political society based on financial exchange and obligation. If this was initially conceived as a temporal distinction, placing natural society in the primeval past and the dawn of mankind, it could readily become a spatial one, applying a similar hierarchy to the different peoples of the far-flung contemporary world. Locke’s famous remark, in Two Treatises of Government, ‘Thus in the beginning all the World was America’,13 conflates primeval pre-society with existing forms of life in the wild. Primitive or ‘natural’ society could still exist, as it did in the America of the native peoples, where natural men and women had neither progressed towards civility nor fallen into ‘luxury’ like Europeans. Those in the state of nature were free and equal ‘within the bounds of the Law of Nature’, and this applied to, among others, the ‘Indians’ of America and the hunter-gatherers of Africa. Those on the other hand who belonged to ‘the Civiliz’d part of Mankind’, lived in a world where laws govern property but also ensure justice and security.

If the implications of Locke’s political theory were ‘liberal’ in the sense that it relieved the ‘natural’ man from the taint of paganism, it did not do anything for slaves, to whom, when he mentioned them at all, he denied all rights. They were placed by him in the state of ‘Captives taken in a just War, . . . by the Right of Nature subjected to the Absolute Dominion and Arbitrary Power of their Masters’.14 This is hard to reconcile with Locke’s broader philosophy of human rights, but it can be understood as representing the ‘political’ Locke, who had drawn up the constitution of South Carolina, vesting absolute authority in slave owners. Locke was, after all, a realist who was fully aware of the importance of slavery to the English economy, and had himself invested in the Royal African Company.15

Locke’s views were symptomatic of the widespread acceptance in the seventeenth and first half of the eighteenth century of slavery among the governing classes of Britain, and in those countries involved in the slave trade. Locke’s distinction between those in a state of nature and in slavery was in non-philosophical discourse generally merged into the loose category of ‘savage’, applied to Africans and the native peoples of the Americas, North and South, but also within Europe to the peoples of the far north, and by the English to Scottish Highlanders and the Irish peasantry. Though the word ‘savage’ always implies difference and condescension, it does not preclude admiration. In satiric or sentimental discourses, American ‘Indians’ can appear as paragons of liberty, to be contrasted favourably with the London haut monde who are slaves to fashion. If for ‘polite’ Europeans vulgar aspirants to gentility were a permanent social irritant, ‘savages’, apart from the few ‘tamed’ as chattels in wealthy households, could easily become objects of fantasy, myth and legend, distanced to remote places, seen in situ only by the most adventurous. The state of savagery as a refreshing alternative to bogus and affected politeness is embodied in the oxymoron ‘Noble Savage’ that first appeared in the satire-laden climate of Restoration England.

The ‘Noble Savage’, though such an idea goes back to Montaigne and perhaps even further in time, was first named in Dryden’s Conquest of Granada (1670),16 and the type had currency in England and elsewhere in Europe all through the eighteenth century, to be given a new meaning in the ...