![]()

CHAPTER ONE

No Peculiar Strictness Is Observed

Slavery and Innovation

In the Eastern Asylum, no peculiar strictness is observed in isolating the white from the coloured patients; nor under the arrangement adopted in this respect is there the slightest difficulty in management originating from the presence of the two races in the same asylum.

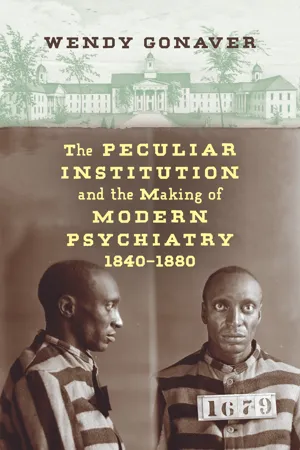

—John M. Galt, “Asylums for Colored Persons,” 18441

In 1841, the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds replaced the office of Keeper with Medical Superintendent and appointed twenty-two-year-old John Minson Galt II to the position.2 One of Superintendent Galt’s first acts was to commission an artist to make a lithograph of the newly named Eastern Lunatic Asylum, which he then used in a circular advertising the institution. The image features the Doric building, as it was called, with its main entry flanked by two evenly sized wings. The building has a simple but elegant form, with regular windows and a graceful Greek-style portico typical of federal-era buildings. Atop each wing is a cupola, offering both decorative appeal and a practical method of ensuring good ventilation to the interior spaces. There are no bars on the windows and no signs of a gate on the attractively landscaped grounds, which feature a vast expanse of closely clipped lawn flanking both sides of a wide central path. The symmetry of the building’s façade is offset by a flock of birds in flight in the upper left corner, and artfully arranged trees, shrubs, and flowers of different heights and textures. Two couples, both men in dress coats and top hats accompanying women in full skirts—one with a parasol—stroll the grounds past a well-dressed man fishing in a stream and a gamboling stag. Of course deer are diurnal and the image appears to capture noontime—the use of the parasol and the shadowing suggest that a bright sun is directly overhead—but the aim is not documentary realism. The effect and purpose of the lithograph are to convey the message that the Williamsburg asylum is a pastoral place of peace and pleasure, to which one should not hesitate to send loved ones in need of mental adjustment.

In the text that accompanies the image, Dr. Galt writes that historically institutions for the insane were “mere places of confinement” owing to their Europeans roots and the need to construct a place where “the insane could be prevented from doing injury to the public.” “The Eastern Asylum,” Galt admits, “was formerly somewhat of this nature.” “Compared with contemporary institutions in Europe,” however, Galt adds, the neatness of the Eastern Asylum and the “attention bestowed on patients” were “always of a high order.” “It was the non-existence of moral means,” Galt opines, “that led to a greater degree of coercion” in the early institution. Happily, Galt concludes, “the humane principles of treatment which modern science has revealed”—kindness, nonrestraint, and healthful environment—“are now most fully and entirely established.”3 Virginia families could now expect the highest levels of care heretofore found at expensive private facilities in the North; this was the reassuring message.

At the heart of moral treatment was the elimination of shackles and chains—and even the threat of such devices—in favor of the salutary influence of a carefully constructed, healthy environment. Moral therapy was challenging to implement, especially in the South where violence and threat of violence were endemic to the slave system. From its inception the hospital admitted free blacks, and under John M. Galt’s tenure the asylum further distinguished itself as the only institution in America to routinely accept slaves as patients and to employ slaves as attendants, though both are conspicuously absent from the commissioned circular.4 Clearly, Galt did not wish to advertise that the Williamsburg asylum did not completely conform to standard practices of nineteenth-century medicine. The contradictions and tension inherent in moral therapy, especially as practiced at an institution that relied upon slave labor and restored enslaved patients to health by deploying kindness so that they might resume their degraded or abusive stations outside the asylum, continually dogged Superintendent Galt. Yet slavery also spurred Galt to experiment with total nonrestraint and endorse outpatient treatment, making the genealogy of these ideas considerably more complex than previously understood, and placing race at the heart of prescient innovations that maximized patient liberty.

Who Was John Minson Galt II?

John Minson Galt II (hereafter referred without the suffix) grew up around the Williamsburg hospital. His great uncle and aunt, James and Mary Galt, were the keeper and matron when the institution opened in 1773. His grandfather and namesake, Dr. John Minson Galt I, was an apothecary and visiting physician from 1795 until his death in 1808. His father, Alexander Dickie Galt, studied medicine in either London or Edinburgh before taking over as a physician in the early nineteenth century. By the time John M. Galt was a teenager following his father on rounds, the facility housed fifty-five patients and had expanded from one building to four.5 He probably knew before leaving to study medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in 1839 that he would one day inherit a place at the hospital.

The time at university was Galt’s first experience away from home for an extended period. A faithful correspondent, he wrote his family detailed letters about his studies and exploits. A frequent topic was the differences that he observed between the North and South, especially the perceptions Philadelphians had about the South. In a letter to his mother, for instance, he wrote that the woman in whose house he boarded “knew a number of the Aristocracy of Virginia, but of its institutions she knew nothing.”6 He also described central heating, with which he was unfamiliar, and observed that every family he met employed black servants and were more “violent against the abolitionists than we are down South.”7 To his sister, he confessed that he had become “much less in favour of abolition than before.”8 Just how committed an abolitionist he was to begin with is questionable if he was that easily dissuaded, but his statement wasn’t a complete reversal of opinion either. Clearly, young Galt had qualms about slavery, an opinion that he openly discussed. He was also aware of key players in the abolitionist movement, writing in 1840 to his father to describe David Paul Brown, the abolitionist lawyer whose keynote address two years earlier at Pennsylvania Hall prompted a mob to burn down the building.9 Galt reported to his mother that his boarding house stood opposite Fanny Kemble’s residence, though he could not have known that the famous actress, only recently returned from her husband’s Georgia plantation, was then embroiled in a battle with her soon-to-be ex-husband over slavery.10

Another frequent topic was the 1840 presidential campaign in which Virginian John Tyler ran as vice president on the Whig Party ticket with William Henry Harrison. The Galt family was well acquainted with the Tyler family. In 1839, John wrote to his sister that he had met “no one as beautiful as Miss E [Elizabeth or “Lizzie”] Tyler,” and that Northern women were less refined than those from Virginia.11 He inquired of his father about Tyler’s sons, who were then enrolled at William and Mary, and whether the family was pleased about the nomination.12 As the campaign got underway, he kept his family apprised of political parades and described the campaign’s headquarters. Perhaps Galt found it absurd to see log cabins carried aloft through the city streets when he knew firsthand the wealth of the Tyler family because he told his sister that he agreed with the “essential principles of the [Democratic] party … but not with their measures nor their leading men.”13 Those principles, in his view, were universal suffrage and equal rights among men. Why, he asked, should he be denied the vote because he didn’t yet own property? To his father he wrote rather cynically that the Democrats were ahead of the Whigs “in everything base & vile.”14 While not exactly a ringing endorsement of the Whig party, John Galt was supportive of Tyler, who was himself a compromise candidate only recently affiliated with the Whigs.

After the Whigs won, John wrote to his father about his hopes that Tyler would adhere to Jeffersonian ideals, especially if the president should die. One month later, President Harrison did die and Tyler was in the White House. Apart from a letter to John from a friend about Lizzie Tyler, in which the correspondent snipingly referred to her as the “young princess” and questioned the sincerity of her distress over Harrison’s death, there is nothing to indicate that Galt was anything other than pleased about Tyler’s performance in office.15 President Tyler combined a strong state’s rights agenda with increased spending on the U.S. navy in service of an aggressive foreign policy that Galt himself would endorse in the coming years. Tyler proved willing to offend and alienate the party that had put him on the ballot for the sake of principle even if it cost him his career, and his views on slavery appeared more moderate than some defenders, including his own secretary of state, John C. Calhoun.16 In both of these regards, John Tyler exhibited qualities that also characterized John M. Galt over the course of his career.

The election of an acquaintance to the nation’s highest office was an exciting diversion, but presumably most of Galt’s time was spent studying. There are hints that John’s ambitions might, at times, have diverged slightly from the expectations of his parents. In a letter to his father he explained that he “took the ticket” for Pennsylvania Hospital rather than for Blockley.17 Blockley was an enormous almshouse complex with a separate hospital for the insane; a practicum there would have been a logical choice for a man destined to head a public asylum, but Galt demurred that the reputable Pennsylvania Hospital was more convenient to his boarding house and had more surgeries to observe. Galt’s arrival at Pennsylvania Hospital happened to coincide with the imminent transfer of insane patients to a new facility in the western portion of the city under the supervision of Thomas S. Kirkbride, one of the champions of moral therapy in America with whom Galt would eventually clash.

Fittingly for the man who would soon implement moral therapy in the Williamsburg asylum, John M. Galt first strove to improve himself through moral discipline. Evincing a faith in the perfectibility of the self, he resolved to “endeavour at once” to find the answers to any medical questions that arose in his mind. Additionally, he wrote in his notebook: “1st feelings. 2nd thoughts. 3. studies & [4] manner of study. 5. action.… I will try to conquer all listlessness by struggling to have it, or to do something else 2nd Whenever I have resolved to do anything, never to give up because I partly fail 3rd to conquer mental disagreeable views, & habits. [4] To endeavor to govern any thoughts.”18 On the same page where he declared these all-encompassing, lofty goals, he also drew some amusing doodles, so it is not clear whether his program of self-improvement was effective. But it is certain that by time he wrote his doctoral thesis, entitled “An Essay on Botany,” Galt was developing a sense that his contribution to the medical field would draw upon his regional expertise. Toward the end of his education, Galt shared his plans to temporarily stay on in Philadelphia after passing his final exams so that he might acquire more work experience. His parents objected, in part because of the failing health of his father and younger brother, reinforcing that Galt’s destiny was tied to Williamsburg.19

In “An Essay on Botany,” Galt posits that physicians ought to study plants both to cultivate “the faculty of discrimination” that is exercised with the classification of species and to enable a practitioner to gather his own medicines. He argues that importing and transporting “vegetable medicines” diminishes their healing powers and renders them liable to adulteration. Why not, he asks, procure them in their purest state? He then lists more than fifty species of flora that he has found growing “within 3 to 4 miles of Williamsburg,” though he does not state whether or how these native plants might be used pharmaceutically. But he does assert that he has “no doubt” that “there are various native medicines used with success by old women and such like practitioners, which on account of their efficacy might be advantageously introduced into general practice.” He avers that these folk remedies would probably be widely used but for “the general want of Botanical knowledge and investigation among country practitioners.”20 Given his description of Thompsonianism, a movement that emphasized herbal remedies and advocated self-diagnosis, as “idiotick [sic] humbug” and of ladies’ interest in botany as uninformed and frivolous, it is perhaps surprising that Galt would nevertheless recognize the value of homegrown remedies and practitioners including, presumably, slave healers.21 While many conventional doctors reviled alternative medicines as quackery and “old women’s conjurations,” Galt did not.22 The apparent contradiction is understandable when interpreted as part of his lifelong effort to reconcile regional practices with mainstream medicine. In this sense, Galt was typical of nineteenth-century Southern physicians who created a distinctive “country orthodoxy” that combined abstract medical knowledge with deference to local know-how and interpersonal relationships.23

The Thompsonian movement was widespread in areas with “heavy slave concentrations” such as Tidewater and Piedmont counties of Virginia, with 64 and 66 percent of the population enslaved during the 1830s and 1840s, respectively.24 The appeal was multifaceted. Herbs were cost-effective for slaveholders and often more efficacious than the harsh remedies of professional medicine. For slaves, self-treatment enabled them to draw upon their own medical knowledge. Galt described his approach as “eclectic.”25 Eclectics shared with Thompsonians an interest in botanic remedies made from native plants, but they believed that educated physicians should be responsible for diagnosis and prescriptive treatment. As a professional, Galt insisted that homecare was inadequate at best and harmful at worst. The eclectic movement was also critical of the Thompsonian emphasis on stea...