- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Between 2009 and 2014, as the nation contemplated the historic election of Barack Obama and endured the effects of the Great Recession, Matthew Frye Jacobson set out with a camera to explore and document what was discernible to the “historian’s eye” during this tumultuous period. Having collected several thousand images, Jacobson began to reflect on their raw, informal immediacy alongside the recognition that they comprised an archive of a moment with unquestionable historical significance. This book presents more than 100 images alongside Jacobson’s recollections of their moments of creation and his understanding of how they link past, present, and future. Jacobson’s documentary work between 2009 and 2014 tracked in real time the emergence of what we now know as Trumpism.

The images reveal diverse expressions of civic engagement that are emblematic of the aspirations, expectations, promises, and failures of this period in American history. Myriad closed businesses and abandoned storefronts stand as public monuments to widespread distress; omnipresent, expectant Obama iconography articulates a wish for new national narratives; flamboyant street theater and wry signage bespeak a common impulse to talk back to power. Framed by an introductory essay, these images reflect the sober grace of a time that seems perilous, but in which “hope” has not ceased to hold meaning.

The images reveal diverse expressions of civic engagement that are emblematic of the aspirations, expectations, promises, and failures of this period in American history. Myriad closed businesses and abandoned storefronts stand as public monuments to widespread distress; omnipresent, expectant Obama iconography articulates a wish for new national narratives; flamboyant street theater and wry signage bespeak a common impulse to talk back to power. Framed by an introductory essay, these images reflect the sober grace of a time that seems perilous, but in which “hope” has not ceased to hold meaning.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Historian's Eye by Matthew Frye Jacobson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Barack Obama, the Icon

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS, 2011

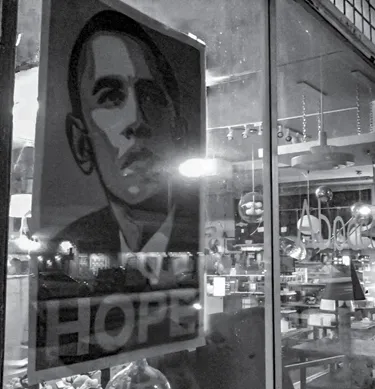

Soon after the first Obama inauguration, conservative commentators like Sean Hannity and Glenn Beck began to protest the very un-American “cult of personality” that had developed around the new president. While it is true that Obama quickly generated a richer iconography than perhaps any other sitting president, it hardly represents a cult of personality per se. This truth became clearer over time, as disappointment with Obama grew notably among progressives, even while ubiquitous images of the president—in places both public and private—continued to multiply. Obama’s iconic image (like his 2008 slogan, “Yes We Can!”) did a great deal of ideological work for a nation whose history is steeped in white supremacy but whose post–civil rights ethos gave voice to hopeful resistance and alternatives.

Having served as president of the Harvard Law Review in the 1990s, a younger Barack Obama noted that interest in his life story in Dreams from My Father testified to “America’s hunger for any optimistic sign from the racial front—a morsel of proof that, after all, some progress has been made.”1 His ascendance to the presidency in 2009 became the greatest morsel ever—more than a morsel. The relationship between Obama and the civil rights legacy remains unsettled: as artist Ricardo Levins Morales soberly points out, it takes a revolutionary visionary to push doors open, but those who walk through them—like Obama—are not likely to be revolutionary visionaries themselves.2 And yet in myriad Shepard Fairey “Hope” and “Change” posters lovingly hung in restaurants, bars, and private living rooms across the country; in kitsch items sold as souvenirs; in “Obama 44” Major League Baseball team jerseys; in stage plays like That Hopey Changey Thing (New York) or Barackalypse Now! (Chicago), the omnipresent figure of Obama, deployed in unexpected places and in a thousand different moods, embodied a public contest over precisely what the “post” of “post–civil rights” might mean, and articulated a widespread yearning to tell a different story about who we might yet turn out to be as a nation.

WASHINGTON, D.C., 2013

The second Obama inauguration felt like a party. The ubiquitous American flags represented a gleeful piece of reappropriation, after generations of public discourse had seemed to sequester the nation’s patriotic symbology on behalf of the Right alone. Like the Obama presidency itself, too, all this exuberant flag-waving put an exclamation point on the disarticulation, once and for all, of “American-ness” from whiteness.

The first inauguration, on the other hand, had felt more like a church service. Even amid the jubilant gathering of 1.8 million people, there was a hush and a reverence for the moment that was unlike anything I have experienced anywhere else. We walked to the National Mall from a friend’s house in Arlington, Virginia, starting at about 4:00 A.M. Even at that hour, shadowy clusters of humanity were drifting in the streets through the darkness toward the mall with us. At first I associated the quiet with the hour. But that peculiar stillness actually characterized the entire day—the most striking thing about that event was not the spectacle, not the scale of this biggest inauguration crowd ever, but the calm and the look of genuine awe and veneration on every individual face. Some version of Never thought I’d see this day was in the eyes of everyone in the multitude—especially but not exclusively the African Americans of a certain age—and also a joyous and unbelieving Isn’t it magnificent? As Obama called on us from the dais “to choose our better history,” what was palpable in the air was a collective sense that this—not the Emancipation Proclamation, not Juneteenth, not Jubilee celebrations, not the ’64 Civil Rights Act—but this at last marked the coming of African Americans’ full citizenship. The vast distance between the pious contemplation of the first inauguration and the rowdy flag-waving of the second measured the extent to which the blackness of the president had been successfully digested and metabolized in the political culture in four short years. A “post-racial” nation, as some wish to suggest? Absolutely and quite obviously not. But over that span, a certain cohort of Generation Z did have the chance to come to consciousness thinking that it was perfectly “normal” for a black man to occupy the White House, and this has to change the nation in the long run.

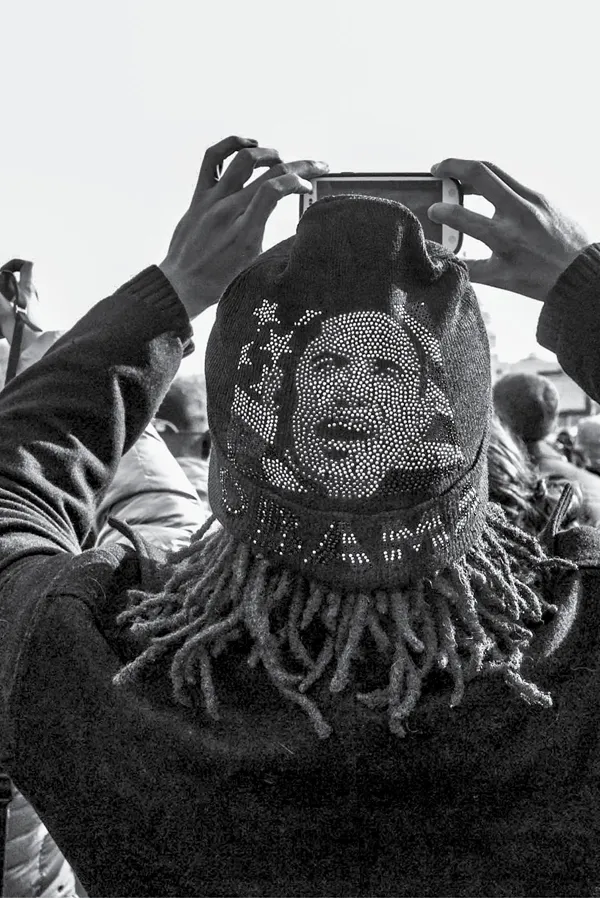

WASHINGTON, D.C., 2013

“Barack Obama’s black presidency has shocked the symbol system of American politics,” wrote Michael Eric Dyson.3 The concentric circles of this photograph—my rendering of this photographer’s rendering of a momentous event that had already been rendered as a souvenir hat—document precisely that shock.

The whiteness of the normative American was written deeply into the nation’s political culture from the founding, and nowhere more forcefully than the normative figure of the president. It has been our great fortune that the founding documents were drawn up in universalist language—phrases like “all men are created equal” lent a rhetorical foothold to later comers like Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Martin Luther King Jr., even if the three-fifths clause, the 1790 Naturalization Act, or George Washington’s efforts to recover his “absconded” slave, Oney Judge, left no doubt as to what the framers actually meant. This was not simply a matter of slavery, but of race more generally: in Euro-American Enlightenment thought, the fledgling democratic experiment depended on conceptions of the citizens’ “reason,” “rationality,” “virtue,” and “self-possession,” all of which were already raced as unique properties of the white European. (A revolutionary-era encyclopedia defined the word “Negro” to include “idleness, treachery, revenge, debauchery, nastiness and intemperance.”4) Which is why the rights of even free blacks were severely curtailed in most regions even before Jim Crow; it is also why white “democrats” could comfortably embrace Indian Removal, Manifest Destiny, Chinese Exclusion, or the abrogation of “inalienable rights” in Hawaii, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. Speaking of the peoples in these new U.S. possessions, Teddy Roosevelt testily swatted down the notion “that any group of pirates and head-hunters” could be transformed “into a dark-hued New England town meeting.”5 This is also partly why Reconstruction governments met with such a storm of white terror in the 1870s, and it is probably why the crushed experiment of Reconstruction is often remembered as a “failed” experiment. The most extreme anti-Obama backlash, in fact, resembles nothing in U.S. history quite so much as it resembles the white response to “black rule” in the 1870s.

Obama likes to narrate his biography as a tale of American exceptionalism and extraordinary “opportunity”—only in America could his story become true. But Obama’s foes and his admirers alike seemed to acknowledge that his ascendance to the presidency ran right to the core traditions and mythologies of white rule. It does not merely shock the symbol system. In a just world it would shatter it.

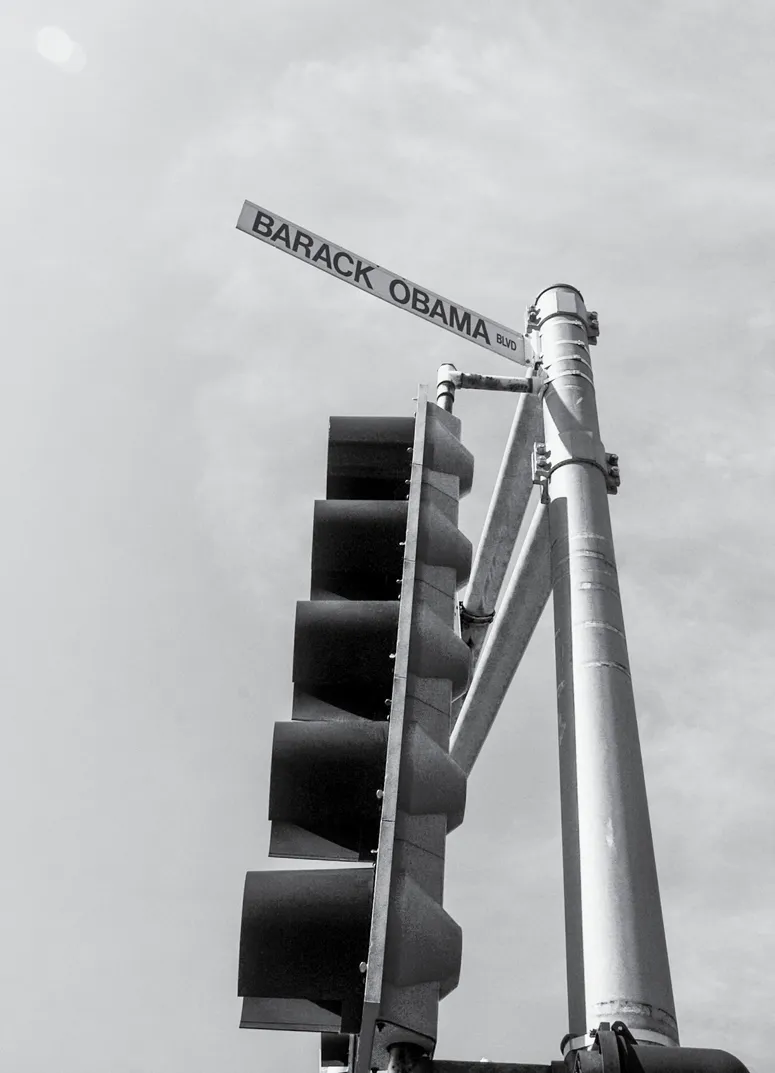

SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURI, 2009

According to Wikipedia, as of 2018 the list of things named after Barack Obama since 2008 includes schools in ten states, streets in four states plus Tanzania, and a mountain in Antigua and Barbuda. It also includes several species appellations in the scientific world: the Obamadon (an extinct lizard), the Aptostichus barackobamai (a species of water trapdoor spider), and Paragordius obamai (a parasitic worm—evidently named by a Republican).6

Delmar Boulevard in Saint Louis was renamed for Obama in 2008. It reflected the widespread desire to mark the moment of the black president’s ascension, even before it was known what kind of president he would turn out to be. This suggests a certain eagerness for national revisionism—the rush was not so much to honor him, but to honor us and to tell a new story about who we are as a post-racial electorate. But the renaming in Saint Louis did not go off without some controversy. Delmar Boulevard was a major east-west artery that had become known as a significant racial dividing line bisecting the city. Many felt that a Barack Obama Boulevard ought to be a north-south artery that did not divide the city’s largely segregated neighborhoods, but connected them. But there were also many in Saint Louis who objected to honoring the newly elected president at all. Alderman Kacie Starr Triplett wrote that she was “completely surprised by the amount of opposition and hate mail recv’d for the proposed honorary name change. … It did successfully pass, but not without a fight.”7

NEW YORK, NEW YORK, 2009

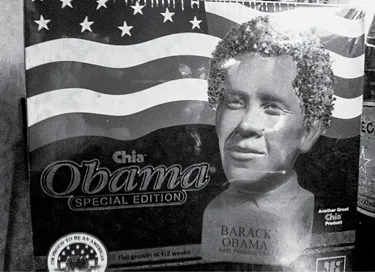

In 1977 Joseph Enterprises introduced the Chia Pet, a terracotta statuette that held water like a vessel but whose porous ceramic surface could host live chia sprouts that looked like fur or hair within ten days or so of germination. The original Chia Pet was a ram, and the first several iterations through the 1980s stuck closely to the natural world—bulls, puppies, kittens, trees. The list of Chia products later expanded to include familiar figures from popular culture like Elmer Fudd, Bugs Bunny, Scooby-Doo, Bart Simpson, or SpongeBob. The Chia Obama (released in 2009 in two attitudes: “happy” and “determined”) represented Joseph Enterprises’ first foray into the realm of historical figures, a project that has since been expanded to include George Washington and Abraham Lincoln on one end of the timeline, and Mitt Romney, Newt Gingrich, Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton, and Donald Trump on the other.

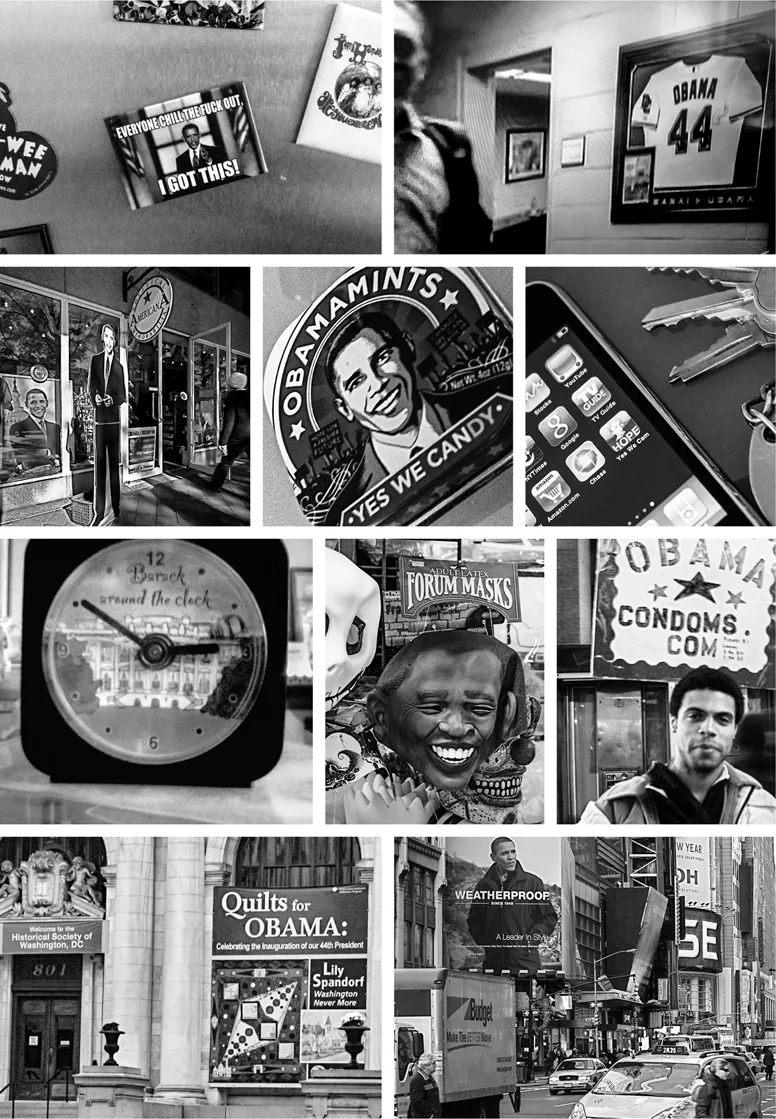

The advent of the Chia Obama came amid a wave of giddy Obama depictions across myriad venues and forms, as the culture absorbed the novel fact of an African American president. There were Obama refrigerator magnets, trinkets, action figures, and dolls, including a ukulele-playing dashboard doll; there were scores of Barack Obama coloring and activity books for children; there was an Obama edition of The Amazing Spiderman comic book, and Obama made appearances in MAD Magazine, Captain America, Archie, and Godzilla; there was a brand of Obama breath mints called Yes We Candy; there were several versions of Barack Around the Clock (a wristwatch, an alarm clock, a wall clock, and a song); and there was the Yes We Cam, an iPhone app that transformed images from one’s photo album into Obama-themed “Hope” posters. The Smithsonian sponsored a “Quilts for Obama” exhibit; Lehigh University mounted an Obama folk-art show; and Cornell University developed a digitized web gallery of “President Barack Obama Visual Iconography.”8 Billboard, for its part, posts the following top ten list of Obama pop songs: “My President” (Young Jeezy), “Bring It on Home” (Mariah Carey), “Jockin’ Jay-Z” (Jay-Z), “Changes” (Common), “Yes We Can” (will.i.am), “Work to Do” (Kidz in the Hall), “Why” (Common, Styles P and Nas), “Letter to Obama” (Joell Ortiz), “Black President” (Nas), and “Keep Moving Forward” (Stevie Wonder).9 In 2009 I met a young man in Times Square selling “Obama Condoms.” And in 2013 Sony Pictures brought us White House Down, a black-president-in-peril film in which Jamie Foxx tells us, “I don’t wanna make history, I wanna make a difference.” In real life, the nation obsessed on the making history part.

BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA, 2011

Obama was the first sitting president ever to visit the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. After listening to a curator’s presentation on Jackie Robinson and the desegregation of baseball, Obama responded, “That’s great. Gotta have everybody on the field.”10 The mythos of this moment is chin-deep and very dense: national pastime and American presidency, sacred spaces of baseball diamond and Oval Office, two of the greatest African American “firsts”—speaker and listeners alike must have felt in their very bones the force of the histories being invoked in the phrase gotta have everybody on the field in this setting. Nor is the association between the national pastime and civil rights politics a casual one. “You’ll never know what you and Jackie and Roy [Campanella] did to make it possible to do my job,” Martin Luther King Jr. once told Robinson’s teammate Don Newcombe.11 Barack Obama might have said the same. The mechanics of social change are such that no nation could get from Nixon’s “southern strategy” in 1968 to Obama’s election in 2008 w...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction. What the Camera Teaches

- 1. Barack Obama, the Icon

- 2. At the Crossroads of Hope and Despair

- 3. Space Available

- 4. American Studies Road Trip

- 5. I Want My Country Back

- 6. Reflections

- Afterword

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index